Captain Robert Scott: Selfless hero or weak leader? Just what is the legacy of the polar explorer 100 years after his death?

Renewed interest in the pioneer on the anniversary of his death at the South Pole

'I do not think we can hope for any better thing now.

We shall stick it out to the end, but we are getting weaker, of course, and the end cannot be far.

It seems a pity, but I do not think I can write more. R. SCOTT.

For God's sake look after our People.'

These were the final, poignant words Captain Robert Falcon Scott put in his diary as he lay dying in a tent in Antarctica 100 years ago.

Next to him lay Edward Wilson and Henry Bowers who also eventually succumbed to hunger, exhaustion and the bitter cold after battling 800 miles back from the South Pole, knowing they had been beaten in the race to get there first by the Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen.

Trapped in their tent as an unseasonally ferocious snowstorm swirled around them, their final resting place was a mere 11 miles from One Ton Depot where life-saving food and fuel awaited them.

The above diary entry was made on 29 March, 1912, and on Thursday at 11am a commemorative service will begin in St Paul’s Cathedral for Scott and his men. It is the same building where King George V attended a memorial service for the polar party on 14 February 1913.

The anniversary of his death has seen a renewed interest in the man resulting in widespread media coverage and a major exhibition mounted at the Natural History Museum "Scott's Last Expedition".

Furthermore, it has led once more to a re-examination of his standing as a great British hero which has waxed and waned.

Dr Huw Lewis-Jones, an expert in polar exploration history, says Scott is a man who appeals to people in different ways: “ He is a figure who has the ability to make people partisan. As much as people admire him, there is a cohort who look down at what he did.”

He adds the perception of Scott has served as a barometer to public feeling and that each generation has reinvented the story for themselves. From “noble death” soon after his tragic end became public, to the 1970s where a process of historical revisionism saw him raised up as an emblem of incompetence and amateurism.

To understand why Capt Scott continues to have such a hold culturally it is necessary to examine his legacy from many perspectives, says Louise Emerson, exhibition organiser at the NHM.

“It is an amazing story and because it took place 100 years ago makes it even more so,” she adds. “They [Scott and Amundsen] made brilliant decisions and mistakes and all that is mixed in together. People want to know more about it. What really did happen.”

Sating the public appetite for just what happened in the snow and ice began in 1913, a year after news of Scott’s death first emerged, when his journals were put on display at the British Museum. By the 1920s it is estimated a million people had passed through to see them.

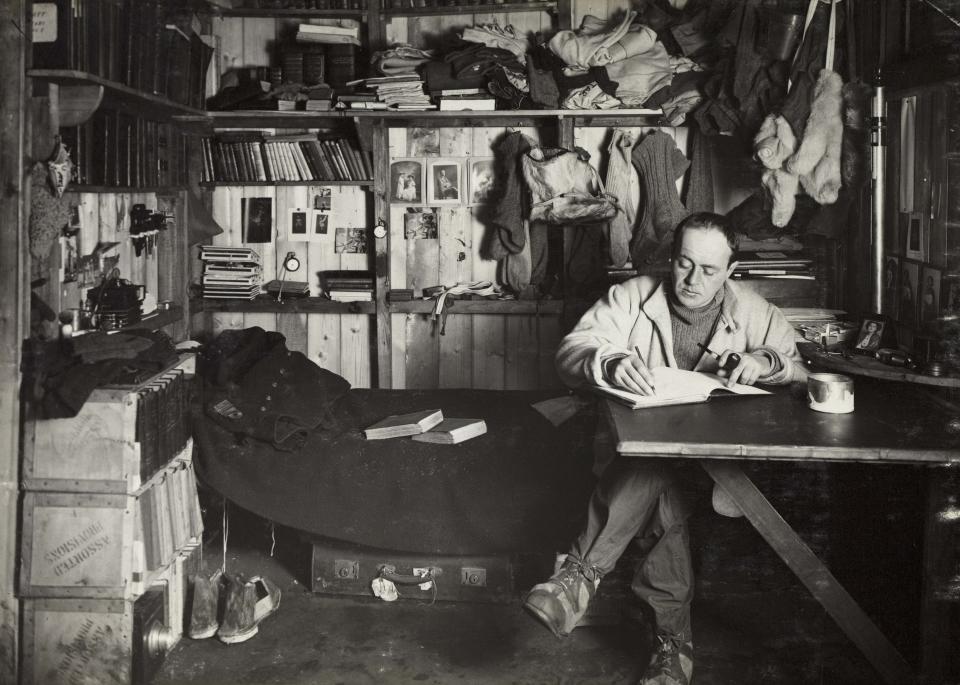

It is the richness of Scott’s diaries and the stunning images taken by the professional photographer he took with him, Herbert Ponting, which provide the powerful combination of fascinating story and remarkable pictures.

“His final diaries are, with hindsight, some of the finest writing under duress in the English language,” says Dr Lewis Jones. “He wrote until he could no longer hold a pen. Only the meanest spirits would be unmoved by his writings.”

[Related gallery:A journey in photos of Capt Robert Scott's ill-fated Antarctic expedition]

It is because of his diary that the public heard of the sacrifice made by Capt Titus Oates who, suffering from gangrene in his feet, sacrificed his life in the hope it would save his comrades by stumbling out of the tent never to be seen again. Scott wrote in his diary “He said: ‘I am going outside and may be some time’...We have not seen him since.”

“He [Scott] wrote beautifully, it [his diary] was really well written. For Amundsen it was a very functional diary,” said Ms Emerson.

Polar adventurer Alan Chambers, 43, who is planning to retrace and complete Scott’s route – the first time this has ever been done - later this year with Dr Ed Coats, 31, said the impact of the writing still resonated today.

“I have read those inserts and they still put up the hairs on the back of your neck. When you think of the condition, where they were, the time in his life, knowing that is the end. And they still put time aside to write ‘make sure you look after our family’.”

“It is inspirational, in a sad way.”

While getting to the South Pole first was one of Scott’s objectives the other, equally important, was the possibility of the scientific discoveries the trip offered.

To this end he mounted the largest and most diverse scientific expedition ever held at Antarctica at that time.

“He took the best scientists of the day who went on to have excellent careers but because of the deaths the science got lost in the story” adds Ms Emerson.

In all, 12 scientists went including two biologists, three geologists and one meteorologist. They brought back with them 2,109 different species of animals and plants - 401 which were new to science.

That sheer dedication to science came to the fore in what became known as “The Worst Journey In The World”. Four months before Scott set out for the South Pole three members of his team – chief scientist Dr Edward Wilson, Apsley Cherry-Garrard and Bowers took part in this mini-scientific expedition.

The aim of the 125-mile round trip was to collect emperor penguin eggs which was only possible in the middle of the polar winter, when temperatures plunge and “daytime” consists only of a few hours of twilight. They returned, barely alive, after 19 days in temperatures of minus 60C.

The weather was so cold that their sleeping bags were constantly frozen and it was reported that even their teeth cracked. Cherry-Garrard wrote afterwards: "The horror of the nineteen days it took us to travel from Cape Evans to Cape Crozier would have to be re-experienced to be appreciated: and any one would be a fool who went again."

Dr Lewis-Jones, author of In Search Of The South Pole, adds that it should be remembered that Scott was a genuine pioneer of science. His team found for the first time a fossilised fern-like plant, known to grow in India and Africa which suggested that the climate there 250 million years ago had been mild enough for trees to grow.

What undoubtedly added to the initial myth of Scott’s story was the time and context in which news of his death reached the outside world. Although he died in March 1912 it was not until eight months later that a search party led by Cherry-Garrard, having waited for the polar winter to pass, discovered the bodies.

He wrote in his diary: “We have found them - to say it has been a ghastly day cannot express it - it is too bad for words.”

It was not until 10 February, 1913, that the Terra Nova arrived in New Zealand and the tragic news could be telegraphed to a Britain – a country already reeling by the loss of the Titanic the previous year.

The announcement stunned the public who as David Crane writes in his acclaimed biography Scott Of The Antarctic: “Less than a year earlier the sinking of the Titanic had brought thousands to St Paul’s Cathedral to mourn, and within four days of the first news from Oamaru [New Zealand] the crowds were out in even greater force.”

Scott’s name was already known to the public well before his team set sail from Cardiff on the Terra Nova on June 15, 1910. He had been to the Antarctic on board the Discovery with Edward Wilson and Ernest Shackleton in 1901. They had even made an attempt to become the first men to reach the South Pole but were forced to turn back.

The Britain that Scott left behind when he headed there was a confident country with a vast empire that stretched around the globe. The horrors of World War I had yet to be visited on that generation and there was a fascination for the unknown lands they were heading for.

Even now, Antarctica, a land mass twice the size of Australia which covers 5,400,000 square miles has only ever been visited by a handful of people.

A topsy-turvy world where summer in the UK is winter there - resulting in four months of almost total darkness.

No satellite phones or internet connection back then to enable information to be relayed quickly - the mail from home arrived once a year and letters were picked up at a pre-arranged post box on the coast of Antarctica.

Today, the region has been extensively mapped, a luxury not at the disposal of the explorers 100 years ago.

As polar explorer Alan Chambers says: “We know where we are going, they did not.”

On Scott’s enduring appeal across all age groups he adds: “It is a story which I think a child, any generation, can learn a lot from. Incredibly inspirational, the story itself is a legacy.”

Essentially, it is the very human nature of the story that ensures it still resonates today, says Ms Emerson of the NHM.

Historian Dr Lewis-Jones agrees. “He was a man who tried and failed and suffered but was brave. We care because he had a go and he did not come back.”

Natural History Museum, Scott’s Last Expedition runs until 2 September 2012.

Scott: From Film Star To Fall Guy, Attenborough Studio, Dr Huw Lewis-Jones, author of In Search Of The South Pole, 30 March, 2012, 14.30

For more details of Scott-related evenings and daytime talks see http://www.nhm.ac.uk/index.html

Yahoo News

Yahoo News