How 1967 changed gay life in Britain: ‘I think for my generation, we’re still a little bit uneasy’

It’s 11.30pm on 14 June 1967. On BBC2, Late Night Line-Up is starting. A saxophone plays as the camera zooms in on a sober-looking panel of experts – a doctor, a social psychologist, a Conservative MP and a writer. They are there to discuss one of the burning issues of the day – homosexuality – and respond to a groundbreaking documentary shown earlier in the evening. That documentary, explains presenter Michael Dean, “made no judgments and passed no opinions. It let homosexuals speak for themselves about their common condition.”

The only person on the panel with the “condition” is Maureen Duffy, whose novel about lesbian life, The Microcosm, had been published the previous year (she was one of the first women in British public life to be openly lesbian). Now 83, she remembers that night as an important moment for gay visibility, but acknowledges that she was in a position of relative privilege. “I was a self-employed writer. I could not lose my job, as some people did if they were discovered to be gay. I had nothing to hide and so it was easy for me to speak up.” And, as a woman, her private life wasn’t criminalised, because the law ignored lesbians. Male homosexuality was still illegal, with “buggery” technically punishable by imprisonment for life. With many men understandably scared to identify themselves, “Those women for whom it was possible did stand up to be counted, made the case that it was unfair and did what they could,” says Duffy.

Fifty years ago this week, and just over a month after Late Night Line-Up was broadcast, the Sexual Offences Act 1967 received royal assent. It stated that “a homosexual act in private shall not be an offence provided that the parties consent thereto and have attained the age of 21 years”. It was the first significant liberalisation of the law relating to sex between men in English history.

The act was the culmination of several attempts to implement the findings of the Wolfenden committee, which had been tasked in 1954 with bringing creaking legislation into line with modern mores. Attitudes to homosexuality were gradually changing, spurred by the work of Sigmund Freud and Alfred Kinsey, as well as arguments about personal liberty. When John Wolfenden concluded in 1957 that homosexual acts in private should not be a crime, even the Archbishop of Canterbury agreed, saying: “There is a sacred realm of privacy ... into which the law, generally speaking, must not intrude.”

In the wake of Wolfenden, pressure groups such as the Homosexual Law Reform Society formed, hoping to keep up the momentum. A thousand people attended its inaugural public meeting in London, to hear the pleas of journalists, a psychiatrist and a bishop. Despite this, parliament kept dodging the issue, until, in 1966, Harold Wilson’s government decided not to stand in the way of private legislation sponsored by the Conservative peer Lord Arran and the Labour MP Leo Abse. The bill was eventually passed in the House of Commons by 101 votes to 16. The quid pro quo for less regulation of personal behaviour was a greater focus on “public order” and “decency”. Some instances of gross indecency, for example, would now be punished by five years in prison, instead of two. And the whole endeavour wasn’t exactly undertaken in a spirit of pride. Lord Arran asked for “those who have, as it were, been in bondage and for whom the prison doors are now open, to show their thanks by comporting themselves quietly and with dignity”. In other words, don’t frighten the horses.

John Carter was 17 at the time and doesn’t have a clear memory of the bill passing; he only realised the significance of the change with hindsight. He came out in the early 70s, after making contact with his university’s gay society, which wouldn’t have existed were it not for decriminalisation. “It meant that people could meet … and freely associate.” That was crucial, he says, because, “if you don’t even have a space where you can go, then people are cruising, they’re cottaging ... It took many years for people who had been constantly looking over their shoulder, being worried, to develop proper ways of relating to each other. Ways that were not just based on sex or compromise or fear.”

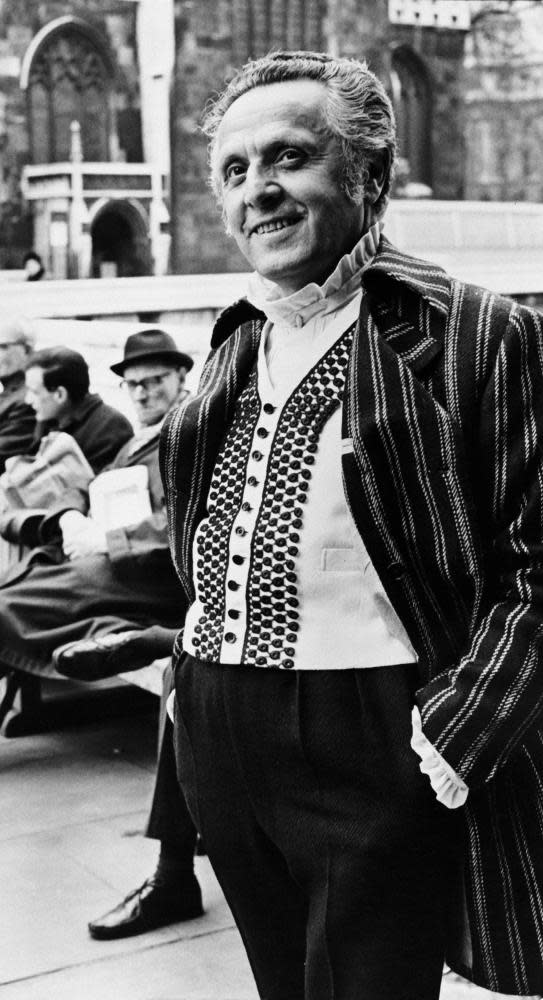

Actor Simon Callow was 18 in 1967 and is similarly vague about the moment of decriminalisation itself. “I wasn’t, as it were, sitting at my table and longing for the bill to be passed,” he says. Rather, the legal situation “was part of the general gloominess which hung around being gay – that you were likely to be a criminal or some terrible pervert or something”. After leaving school, Callow got a job in a bookshop, and wrote a letter to Laurence Olivier about how much he admired what he was doing at the Old Vic. Olivier replied: “If you like it so much, why don’t you come and work here?” That changed everything for him. “When I went to work in the theatre, I immediately saw something completely different – which was an environment in which there were lots of gay people who were all perfectly cool with being gay, although they never said it publicly.” But the respite was never total. “[Playwright] Joe Orton was killed by Kenneth Halliwell at that time and one of the people at the box office was a very close friend of his. So again one had this strange association with violence and crime and desperation with the lives of gay people.”

It wasn’t just the news that painted a grim picture of what it meant to be gay. “The box office manager had a copy of a book called Last Exit to Brooklyn, which was a famous ‘shock’ novel at the time, in which the lives of transvestites and prostitutes were laid bare, and I did for a moment think: ‘Oh my God, I really don’t want my life to be like that.’ It was always a problem, as we now say, of positive imagery of homosexuality.”

But there were glimmers of hope, too. “Hockney was such a blessing in that context. Out came David in the 60s doing these wonderfully witty, funny, light and joyful depictions of gay life and that really was a huge, huge boon.”

Callow agrees that it’s possible to overstate the impact of the change in the law on people’s lives – and that outside subcultures such as the theatre gay life continued to be very difficult. “It said you could have sex on your own and if you were over 21 with another man in your house. If there was anybody else in the house it was illegal. It was an extraordinary, weird piece of legislation when you look at it now.” Not only that, but “there was a sort of reign of terror for a couple of years where the police – almost as if they were annoyed that now it wasn’t illegal any more – were determined to catch as many people as they could within the terms of the legislation.” Prosecutions for homosexual behaviour actually went up in the years following the act. Callow notes that those who could do so still felt the need to leave the country in order to live gay lives, with Tangier, in devoutly Muslim Morocco, providing an atmosphere of relative openness for thousands of British tourists.

Callow left London in 1968 to go to university in Belfast, which he likens to stepping into a time machine (the 1967 act didn’t apply there, and male homosexuality remained illegal until 1982). “Then again,” he says, “life is very complex.” There were gay men there who “had perfectly nice sex lives who managed to dodge the law carefully”, with scenes to rival London and Tangier in their bohemianism, if you knew where to look. “I came across someone who worked in the bed and breakfast where I first stayed when I was in Belfast who was an Englishman – a very, very flamboyant Englishman with a Belfast boyfriend, whose particular pleasure it was to dress up as his mother along with other gentlemen. They all addressed each other as Mrs this and Mrs that. And I found myself being invited to supper there where everyone was playing bridge dressed up.”

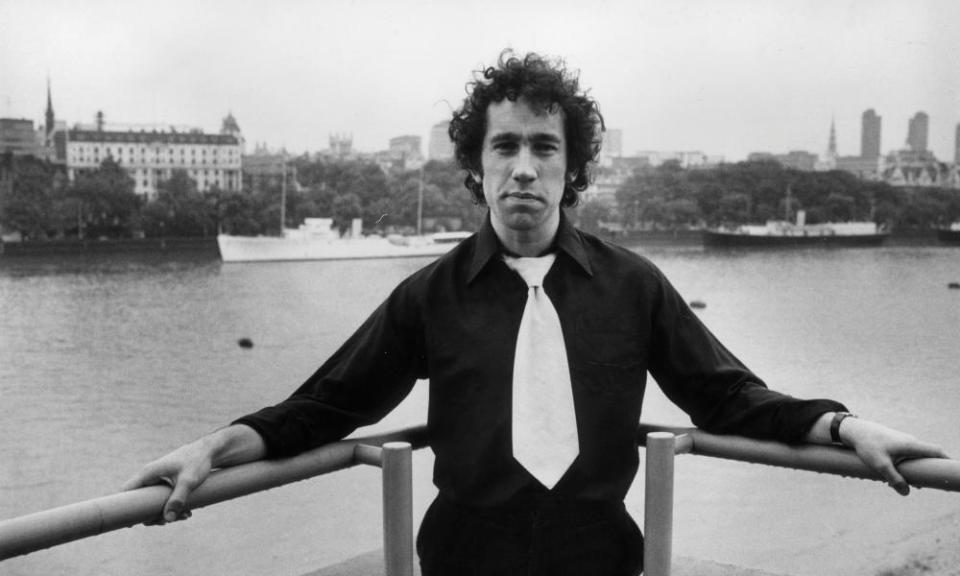

At the same time, in the west of the city, a young Terry Stewart was growing up in a working-class Catholic family. “You’re talking about a period in the north of Ireland when it was difficult to be heterosexual, let alone homosexual,” he says of the era’s stringent moral codes. Aged 13, he wasn’t watching Late Night Line-Up, or contemplating David Hockney, but listening to Scott McKenzie singing San Francisco on the radio and dreaming of a different life. Stewart was viciously bullied at school for reasons he couldn’t then understand; he now recognises it was homophobia. By the time he was 18, he was beginning to explore his sexuality, but “wasn’t really in a position to do much about it”, because he thought he was the only one.

Salvation came in an unlikely form. He was watching Whicker’s World, Alan Whicker’s globetrotting documentary series about people’s lives, “And this one was about a gay marriage in America. I thought: ‘Oh my God, I’m not the only one!’ and, of course, one of my brothers came in and shouted: ‘Turn it off!’ because it wasn’t the sort of thing that a young Catholic Irishman should be watching.”

Stewart knew he couldn’t be himself in a place where homosexuality was still illegal, and, short of San Francisco, London seemed like a decent bet. But on his second visit to a gay bar he found himself confronted with a familiar face. “He was a friend of mine from Ireland and I thought: ‘Sweet Jesus, what am I going to say here?’ And I went: ‘Oh, the Guinness is really good in here,’ and he was like: ‘Oh fuck off with the Guinness, you’re not here for the Guinness. Are you gay?’ and I said: ‘Oh, I might be.’”

It was the mid-70s, and new forms of gay association were emerging, enabled by the change in the law. Stewart’s friend from home told him about a squat in Brixton, south London, and he decided to investigate. He ended up living there, with 40 or so other gay men, for the next few years, while working as a road sweeper and “skipping” for furniture (retrieving items from skips). Despite the support network, it was still a dangerous time. For the police, he says, “We weren’t quite as bad as black people, but they certainly wouldn’t allow the homosexuals to start having their way.”

They raided the squat once while Stewart was there, but sometimes their lack of action was just as frightening. “There was another occasion that our squat was firebombed. I was coming up the street and I could see the flames coming out of the house. The police had arrived and they said: ‘Oh, it’s just the queers,’ and they disappeared, they just went. So you weren’t given any protection from the authorities in terms of homophobic attacks, which were quite prevalent.”

It wasn’t until the following decade that the uncertain legal status of gay men had a direct impact on Stewart’s life. When it did, it was devastating. One morning in 1981 he was arrested by two police officers in a public toilet in Charing Cross Road, where he had stopped on his way home from getting his bicycle insured. There were no other men present, and Stewart didn’t at first know what he was being arrested for: he was told it was “importuning”. He says now: “Don’t get me wrong – I’m not a moral Mary, I’m well able to cottage. But in this particular incident, I was not doing anything.” He denied the charge all the way to the crown court, but was found guilty by a majority verdict and fined £20 (about £80 today). Stewart recently told his story in the More4 documentary Convicted for Love. His criminal record remains in place today.

At the time of his arrest, Stewart was well-known and widely liked in his neighbourhood, and many people, gay and straight, turned out to support him. Now, he describes himself as a “pillar of the community” and is the LGBT representative on the Met’s independent advisory group in “the royal borough of Hackney”. (“Is it royal?” I ask. “Well, there are enough queens here!” he shoots back.) But he still feels discriminated against.

I ask how he feels about the anniversary of decriminalisation. “I would say partial decriminalisation,” he says. “Because it wasn’t decriminalised. I mean the very nature of ‘two consenting adults in private’ – the word private’s very important, because I could book a hotel room with my partner and have sex, but that’s a public place. Even when we go into our bedroom and lock the door, there’s other people in the building. There’s all kinds of stuff where the law did not decriminalise us at all.” He said the conviction had a big impact on his health, and his ability to pursue his chosen career, social work. “At the end of the day,” he adds, “there were men who came out of the courts, they weren’t able to deal with it, they killed themselves. People’s family lives were wrecked. A whole plethora of wreckage. And there was absolutely no need for it.”

Stewart believes the 50-year mark represents an opportunity to finally remove the stigma from the thousands of men who were convicted, like him, of importuning in a public place – a law that was repealed in 2003, but is not eligible for a “disregard”, in contrast to the offence of gross indecency, of which Alan Turing was convicted. On 27 July, he is launching a petition calling for Amber Rudd to take action.

The anniversary is just as bittersweet for Chris Brocklesby, who was 21 when the act passed. He says it’s a reminder of a very dark period. “I look back on it and I think, yes there was [the sense of] being a member of a secret society, and obviously we all managed to find ways of having sex and having partners and so on. But you always felt uneasy. And I think for my generation, we’re still a little bit uneasy and still a little bit in the ghetto.” He retains a reflexive suspicion of those who once took great pleasure in locking men like him up. “I remember, a few years ago, the police were advertising for members of ethnic minorities and gay people, etc, and I thought: Yeah, well, I don’t quite trust it.”

Brocklesby recalls the heady days of the early 70s, when the efforts of the rather sober Homosexual Law Reform Society gave way to the defiance of the Gay Liberation Front, inspired in part by New York’s Stonewall riots. “Gay lib suddenly happened,” he says. “Of course it wasn’t long after that you started getting gay pride marches.” The first one, in 1972, attracted 2,000 men and women – and ended in a giant picnic in Hyde Park. Brocklesby went a few years later. “I was a teacher and I was actually concerned about being recognised in public,” he says, but he braved the exposure in any case. “It finished at Jubilee Gardens on the South Bank. And we were astonished because it filled the place.”

Then darkness descended again. In 1988, with the Aids crisis at its peak, the British government decided to kick the gay community while it was down, using the infamous section 28 to ban any “promotion” of homosexuality in schools, including “the acceptability of homosexuality as a pretended family relationship”. “At that stage I felt that Mrs Thatcher had actually declared war on gay people,” says Brocklesby. “And you know, we were not breaking the law. There was terrific resentment. I went on marches against that.” Section 28 was repealed only in 2003 (2000 in Scotland).

Duffy echoes his point. Today, whenever she speaks to gay audiences, she warns: “We must never think that it’s all won for ever. Anything can be reversed. And in many parts of the world, it is still punishable with the death penalty.”

The 50 years since 1967, despite their many triumphs, have presented gay people with the challenge of dealing with a legacy of shame and repression. And, as Stewart’s story shows, the Sexual Offences Act was far from being the end of state-sponsored persecution.

That some wounds are yet to heal isn’t surprising for the author of The Microcosm. “From Wilde onwards,” says Duffy, “we’d had decades of prosecutions and almost torture – the case of Alan Turing, for instance. It takes a long time to recover from that.”

Yahoo News

Yahoo News