1968 Mexico City Games marked by protest, falling records

The 1968 Olympics could not escape the turmoil of their times.

A gold medal gymnast silently rebelled against the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia. Apartheid South Africa was disinvited in order to quell a threatened boycott. And two American sprinters raised their fists in a poignant and powerful show of strength.

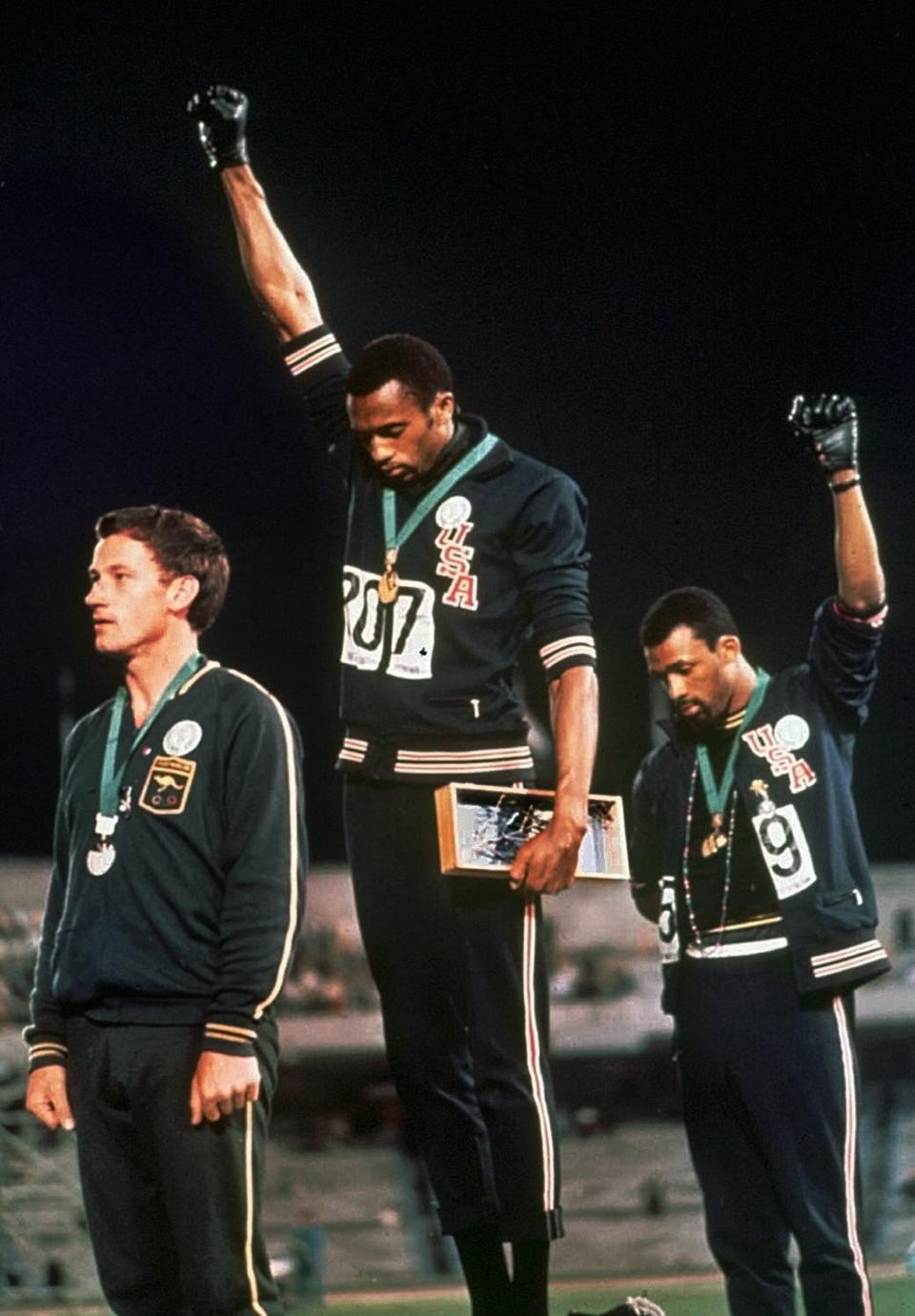

The thin Mexico City air helped runners rewrite the record books, but the lasting image from the ’68 Games is what 200 meter medalists John Carlos and Tommie Smith did on the victory stand: With their feet bare and their heads bowed, the two Black Americans defied the Olympic power structure by raising a gloved fist to protest racial injustice.

“That was my concern,” Smith, the gold medalist, told The Associated Press four decades later. “Not so much how fast Tommie Smith ran, but a nation in peril.”

Smith and Carlos were expelled from the Olympics, receiving death threats when they returned home. But like Muhammad Ali before them and Colin Kaepernick after them, they were eventually lauded for their courage.

“People didn’t want to understand what the fist meant. They tried to equate it to the Black Panthers. That was their choice,” Carlos said after receiving an award in Boston in 2009. “But if you look at my hand, there’s five fingers, five individuals. They’re versatile but independent. They have no power, but when they are together, they become powerful.

“I think, 40 years later, they’ve started to get the message. We can leave the fist behind us,” he said, a day after Barack Obama was inaugurated as the United States’ first Black president.

“It was all worth it,” Smith added.

POLITICS

With the Vietnam War raging in Asia, the Soviet Union expanding into Eastern Europe, and racial strife boiling to the surface in the United States and South Africa, Olympic officials struggled to keep the Mexico City Games apolitical.

After attempting restore South Africa after it was banned from Tokyo in 1964, IOC President Avery Brundage backed down when other African countries, the Eastern bloc and African-American athletes in the United States threatened to boycott.

Brundage, who as USOC president in 1936 tolerated the Nazi salutes in Berlin, also pushed for Smith and Carlos to be suspended over their raised fists; when American officials balked, he threatened to expel the entire U.S. track team. The two athletes were sent home.

Czech gymnast Věra Čáslavská won over the crowd by performing her floor routine to “The Mexican Hat Dance” and wound up sharing the gold medal with Larisa Petrik of the Soviet Union -- but only after a puzzling, after-the-fact score revision. During the Soviet anthem, Čáslavská lowered her head and looked away, a silent but courageous show of defiance that had repercussions for her career.

The 1968 Games also featured the debut of separate teams from East and West Germany.

HIGH TIMES I

At 7,350 feet (2,240 meters), Mexico City remains the highest elevation for a Summer Games, with the thin air credited for a near-total rewrite of the sprinting record book. New standards were set in every men’s track event up to 800 meters, including relays, as well as the long and triple jump; Olympic records fell in the high jump, pole vault and the discus and hammer throw.

Most memorable among them was Bob Beamon’s first attempt in the long jump, which went so far that he exceeded the limits of the electronic measuring system and a tape measure had to be brought in. When at last the distance of 8.90 meters was announced, the American remained in a fog because he was not familiar with the metric system.

After bronze medalist Ralph Boston explained to Beamon that he had jumped 29 feet, 2 3/8 inches -- breaking the old world record by almost two feet (21 5⁄8 inches, or 55 cm) -- he was overwhelmed and collapsed.

Although the altitude no doubt helped, no other competitor in Mexico City approached the old record, let alone the effort that came to define a term: Beamonesque. His record stood until 1991.

HIGH TIMES II

Mexico City was the first Olympic games to have doping control, with Swedish pentathlete Hans-Gunnar Liljenwall the first to be stripped of a medal. The third-place finisher tested positive for excessive alcohol after drinking several beers to calm his nerves before the pistol shooting competition.

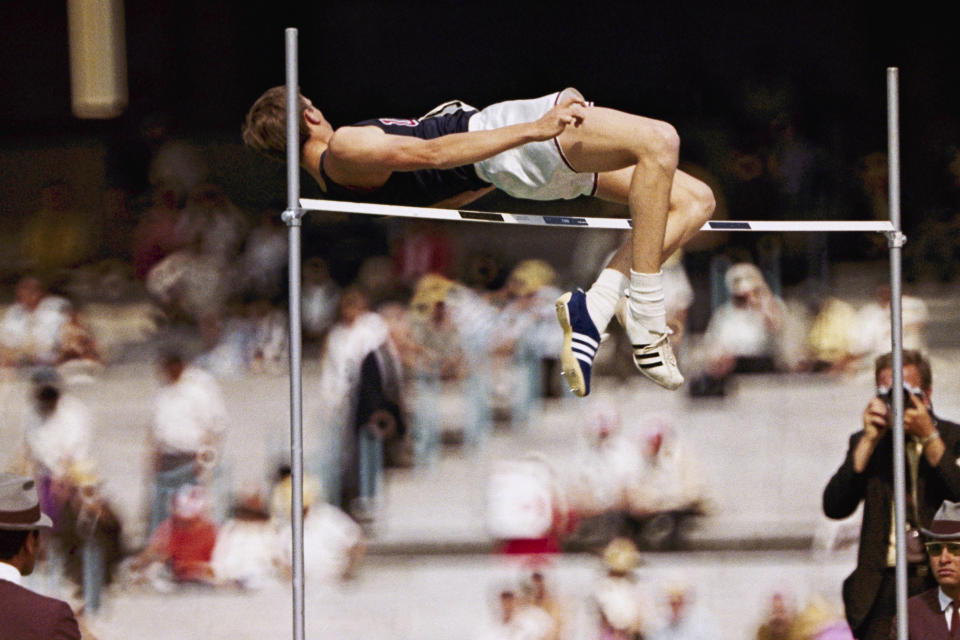

HARDLY A FLOP

High jumper Dick Fosbury took gold with a pair of mismatched shoes and an innovative technique he perfected as an engineering student.

Since the first modern Olympics, high jumpers had employed techniques from a standing jump to a scissors kick to straddle to a roll -- all of them feet first. A failed straddler, Fosbury instead turned his back to the bar, throwing his head over with his torso kicking behind.

The “Fosbury Flop” is now the dominant technique in high jumping.

OLYMPIC FIRSTS

Mexican hurdler Enriqueta Basilio lit the cauldron at the Opening Ceremony -- the first woman to be so honored. U.S. discuss thrower Al Oerter became the first track athlete to win an event at four straight Olympics. Future IOC President Jacques Rogge competed in yachting for the first of three appearances. It also was the first Olympics to be held in a Spanish-speaking country.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News ![FIK]LE - In this Oct. 12, 1968, file photo, Mexican hurdler Enriqueta Basilio, the first woman to make the final run of the torch and to light the Olympic flame, carries the Olympic torch up the 90 steps to the Olympic flame cauldron in the Olympic Stadium during opening ceremonies for the Olympic Games in Mexico City. (AP Photo/File)](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/2PPdJCB5h1FVtf3qhYAEjw--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTY0Mw--/https://media.zenfs.com/en/ap.org/49522576e87a2864da450bb3d0e9dac2)