'We have abandoned the poor': slums suffer as Covid-19 exposes India's social divide

Cooking, cleaning, and food shopping have been a shock to Anisa Agarwal. Pre-pandemic, married to a wealthy tile manufacturer, her life in Gulmohar Park in Delhi involved a cook, maid, driver and cleaner who came to her house every day.

But despite her total dependence on them, Agarwal, 44, has not allowed her staff to enter her home in four months.

“They live in such crowded rooms that I can’t trust them not to bring the virus. They do try to be careful, I know, but their living conditions make it impossible. Social distancing or frequent handwashing are impossible,” says Agarwal.

Related: Half of Mumbai’s slum residents have had coronavirus – study

When the lockdown eased, some of Agarwal’s friends urged her to call at least the driver back to make her life easier. She refused, insisting that being near someone who shared the same room with six people posed a risk to her.

“You see, I was right,” she says on hearing about survey that found over half of the people living in Mumbai’s slums have had the coronavirus, compared with 16% of non-slum residents. “You can’t protect yourself against the virus when you share the same toilet with 50 families.”

Like most Indians, Agarwal has never given much thought to slums – the fetid, dank, dark places where domestic servants, factory workers, plumbers, electricians and security guards live when not serving the wealthy. Whatever diseases were prevalent there could not possibly, it was thought, penetrate gated communities, high-rise condominiums or luxury homes.

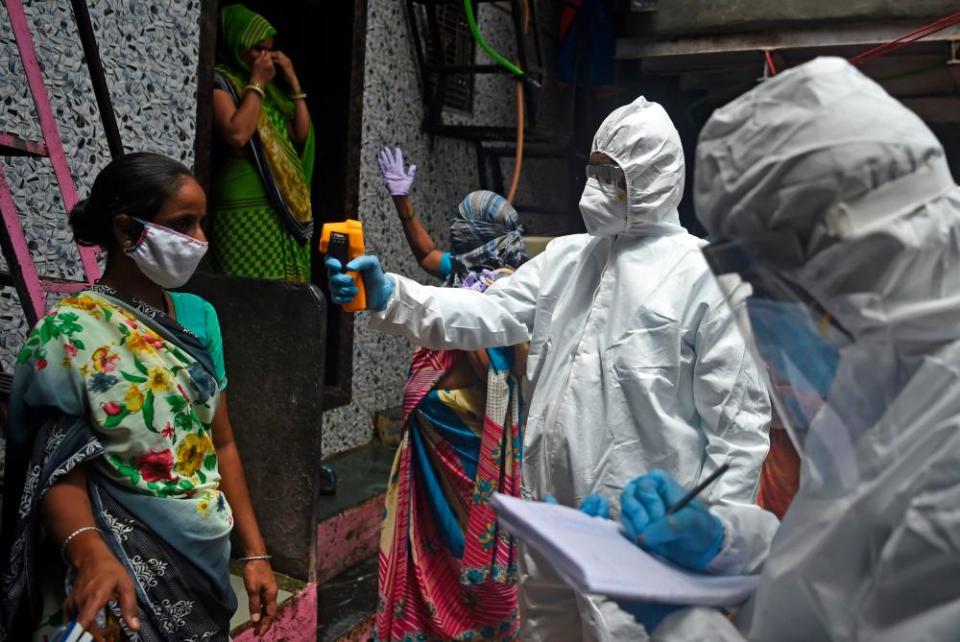

However, Covid-19, has shown it respects no silos. The outbreak has exposed slums as virus hotbeds because of their insanitary and crowded conditions, often with no running water, light or ventilation and with toilets serving hundreds. With no space even to cross your legs, social distancing is a joke.

It is the residents of these slums who go to work in affluent homes, offices, and shops – with some carrying the virus. The problem that India has resolutely ignored for decades – the lack of decent housing for the urban poor – has come to bite the top echelons of society.

On Sunday, India reported almost 55,000 new coronavirus cases, bringing the national total to 1.75 million. The month of July alone saw 1.1 million cases. At least 37,364 people have died in India so far.

The lives of the poor have always mattered too little in India.

Harsh Mander, social activist

“The indifference towards slums comes from the lack of any social obligation by the middle class and rich,” says Jitendra Awhad, housing minister in Maharashtra, which has Mumbai as its state capital. “No one bothers where or how their driver or maid lives. It’s of no concern to them.”

Social activist Harsh Mander points out that even when thousands died of bubonic plague in the 19th century in what was then Bombay, city administrators recognised that the surest defence against future pandemics was well-ventilated, decent housing for workers.

“It is a lesson we refuse to learn, because the lives of the poor have always mattered too little in India. In this pandemic too, we have effectively abandoned the poor in their crowded unhygienic habitats. Middle-class people fail to recognise how closely our destinies are tied, and indeed our survival,” says Mander.

Some 100 million Indians live in slums, a figure that will only grow with rising urbanisation. A 2010 report by McKinsey predicted that 590 million Indians will live in cities by 2030. With little or no planning, many cities offer toxic air, congested roads, crumbling infrastructure and no low-cost housing for the poor and migrant labourers.

Yet it is a rare event for any politician, TV channel, economist or policy maker to discuss the need to eradicate slums. In newly built luxury flats with huge rooms and open spaces, the room allocated for the servant is a windowless cell so small the occupant needs to curl up in a foetal position in order to sleep.

The one exception to the silence on slums is Dharavi in Mumbai. Talk of redeveloping Asia’s largest slum has dragged on for over five decades without progress.

Dharavi quickly came to symbolise why India’s middle and upper classes need to pay attention to slums – they cannot expect to avoid being singed when a conflagration breaks out, as the virus did, in Dharavi.

In the past few weeks, authorities have managed to subdue the contagion there. Its residents are desperate to earn again but their rich employers are too frightened.

Dr Rohit Roy, director of the National Institute of Public Finance and Policy, believes the pandemic is a perfect moment to eradicate slums, if not for the sake of the poor, then for public health. “It is obvious from the Covid-19 situation that a slum-free India by 2023 should be our objective,” he says.

We must first start thinking of the poor as humans

Rajeev Sadanandan, former health secretary in Kerala

“The government can give builders land. Let the builder build homes that families above a minimum wage can afford by taking out a £15,000-20,000 mortgage. Let the builder make a 15-20% profit,” says Roy.

In Maharashtra, Awhad plans to ask the cabinet to approve a plan under which new industrial development areas must set aside 20% of the land to house workers. “It’s only one small concrete step but it’s a start,” says Awhad.

That stranded migrant labourers simply started walking home with no expectation of help earlier in the pandemic showed the lack of what Reddy calls a “social contract” between rich and poor to ensure decent housing for all. Indian society also lacks what he calls “fraternity” – the sense of everyone abiding by the same mutually beneficial rules.

“We are good at one-off events, at big annual festivals or big standalone spectacles. But we’re not good at the things that require sustained, daily, fraternity such as looking out for one another,” he says.

Rajeev Sadanandan, a former health secretary in Kerala, is not optimistic that lessons will be learned. “We must first start thinking of the poor as humans and I don’t see anything to indicate such a shift,” he said.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News