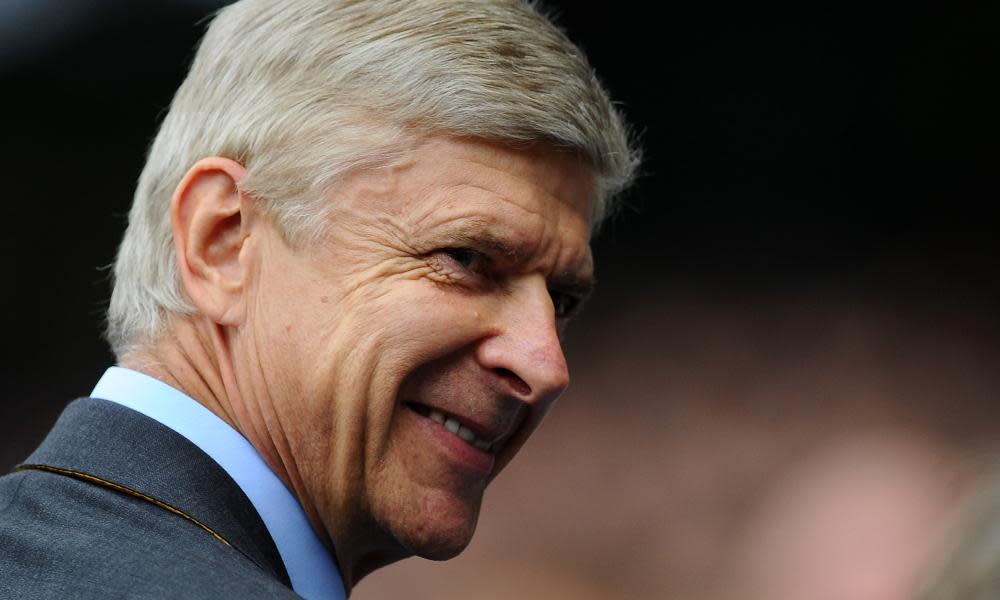

Adieu, Arsène Wenger – artistry in hobnail boots

He arrived in Britain like something from outer space. In 1996, as the leaves were turning red on Avenell Road, Highbury, Arsenal’s new manager took up the reins so recently in the hands of the Bergkamp-buying, blazer-wearing Bruce Rioch. How would Arsène Wenger fit with the likes of Joe Kinnear, Harry Redknapp, Gerry Francis, Kevin Keegan and Ron Atkinson, all at the time, as football argot has it, plying their trade as managers in the Premier League?

He wore glasses. Not just any old glasses, but full-on cultural studies lecturer about to illuminate the world of Derrida, Barthes and semiotic analysis glasses. He was French – French! – with a good helping of Alsatian. And he had come via Japanese club Grampus Eight, which nobody had ever heard of, even though Gary Lineker had played for them.

Wenger spoke five languages often at press conferences, and looked like Professor Yaffle from Bagpuss. His home life could only be imagined as a mash-up of reading Proust while listening to Juliette Gréco, eating sushi and making intricate, multilingual training plans. No wonder the tabloids led the charge with headlines that read: “Arsène Who?”

We soon knew. Within 100 games, Wenger’s Arsenal had won the near-mythical league and cup double. Apparently, all he had done was banish chocolate and encourage players to stretch properly and drink lots of water, banal advice common to any carbon-copy New Year, New You/beach body regime. Could it have been that simple all along?

No. While Wenger was importing healthy doses of the new-fangled “sports science”, he was also effecting a strange alchemy. At Arsenal, he inherited one of the great defences in the history of English football – Tony Adams, Nigel Winterburn, Lee Dixon, Martin Keown and goalkeeper David Seaman – and set about augmenting it with secret knowledge. Out of the French system based at the new national training centre at Clairefontaine, of which English football professionals had scant knowledge, sprang genius: Patrick Vieira, Emmanuel Petit, Nicolas Anelka and Thierry Henry, a significant cohort of the team that won the World Cup in 1998.

The result was a club transformed. A traditional, conservative, though often successful, defensive philosophy gave way to a team of flair, panache, elan and a whole melange of other French words. But there was grit in this particular huître; accompanying all the artistry and subtlety was a blizzard of red cards, as Arsenal’s first team clogged their way to dominance. This was Rudolf Nureyev in hobnail boots.

And therein lies the fun and the contradiction of Arsène Wenger. For all the austerity – even asperity – of his demeanour, he’s a [cue Isaac Hayes singing the Shaft theme] complicated man. One could be forgiven for thinking, over the years, that behind Wenger’s connoisseurial approach to football lies someone not averse to the game’s occasional descent into aggro.

Wenger liked a ruck, squaring up to Ferguson, Alan Pardew and Martin Jol, against whom I wouldn’t fancy his chances

His team, after all, was involved in the notorious pizza-throwing incident of 2004, in which a fixture at Old Trafford that ended Arsenal’s run of 49 games unbeaten culminated in Cesc Fàbregas getting handy with a slice of Meat Feast and leaving Alex Ferguson with pepperoni on his face. These details, by the way, have emerged only recently, both sides having observed a hilarious omertà on the affair.

And Wenger himself liked a ruck, squaring up to Ferguson, Alan Pardew and Martin Jol, against whom, frankly, I wouldn’t fancy his chances. But perhaps his finest achievement in the arena of would-be pugilism was the playground slapathon he enjoyed with José Mourinho in 2014. In his book about Mourinho, Up Close and Personal, journalist Robert Beasley quotes the special one on Wenger: “I will find him one day outside a football pitch and I will break his face”, confirmation, if we needed it, that Mourinho is a labile narcissist with no class.

Wenger, in other words, embodies all the frailties we covertly empathise with and even admire; stubbornness, petulance, refusal to admit to infractions that have happened in plain sight. I’ll put it bluntly: I’ve even warmed to the way he steadfastly ignored the calls for his resignation, which displayed a very human unwillingness to be pushed around by Twitter experts (eyes on you, Piers Morgan, wretched ingrate) and bolshie fans. When you can turn a blind eye to light aircraft trailing Wenger Out banners over north London, you’re proving your mettle just as much as your obstinacy.

I loved his anguished martyrdom as he stood, arms outstretched in mimicry of crucifixion, having been sent to the stands in disgrace. I loved his inability to master the zip on his ludicrous insulated coat.

And now he is leaving English football forever changed and certain never again to see a tenure of such length and distinction. Arsène: he came, he “did not see” the incident, he conquered.

• Alex Clark is an Observer columnist

Yahoo News

Yahoo News