Agatha Christie novels edited to remove potentially offensive language

First Roald Dahl, then James Bond … And now it’s Agatha Christie’s turn to be in sensitivity readers’ line of fire.

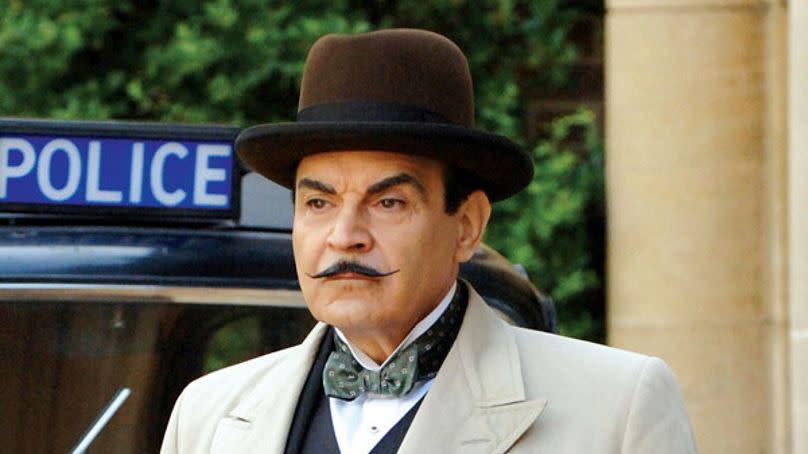

The British writer's classic works have been rewritten to avoid "offending" contemporary readers, with the adventures of Miss Marple and Hercule Poirot to be rewritten and edited by Harper Collins to remove any language that might be seen as offensive.

Brand new editions of the entire Miss Marple series and some of the Hercule Poirot novels will see revisions to passages and even entirely remove others.

The amendments to the books, published between 1920 and 1976, the year of Christie's death, include changes to the narrator's inner monologue. For example, Poirot's description of another character as "a Jew, of course" in Christie's debut novel, 'The Mysterious Affair at Styles', has been stripped out of the new version.

In the same book, a young woman with a "gypsy style" becomes simply a "young woman". Other sentences have simply been rewritten for no apparent reason.

In the 1937 novel 'Death on the Nile', references to "Nubian people" have been removed throughout, as well as an extract when the character Mrs Allerton complains that a bunch of children are pestering her. In the original, Allerton explains: "They come back and look, and look, and their eyes are just disgusting, just like their noses, and I don't think I really like children." In the new edition, this becomes: "They come back and look, and look. And I don't think I really like children."

Ditto for Miss Marple. Throughout the revised version of the short story collection 'Miss Marple's Final Cases and Two Other Stories', the word "native" has been replaced with "local." A passage describing a servant as "black" and "grinning" has been revised and the character is now simply referred to as "nodding," with no reference to his race.

In the new edition of the 1964 Miss Marple novel 'A Caribbean Mystery', the amateur detective’s musing that a hotel worker smiling at her has “such lovely white teeth” has been removed - as has the description of a black woman as "black marble" and that of a judge with an "Indian temperament".

HarperCollins released some of the reissues in 2020, with more set to be unveiled.

This is not the first time the content of Christie’s novels has been changed, as her 1939 novel 'And Then There Were None' was previously published under the title 'Ten Little Niggers', which was last published under that name in 1977.

Historical revisionism rears its ugly head

These changes to Agatha Christie’s oeuvre come after similar changes to Roald Dahl's classic children's books, as well as Ian Fleming’s spy novels.

The censorship of Roald Dahl's editions caused a stir, with writer Salman Rushdie and British Prime Minister Rishi Sunak among those who called for literary works to be "preserved" rather than "retouched".

To mark 70 years since 'Casino Royale', Fleming’s first book featuring James Bond, several changes were made to remove “offensive” language.

We spoke to Andrew Lycett, Ian Fleming’s biographer and author of the definitive Ian Fleming biography, ‘Ian Fleming’, to get his opinion on the changes to the 007 novels. He noted that “You can’t change James Bond. He is what he is. He is a character of his time" and that the edits were “form of censorship”.

While the books of Fleming and Christie do feature attitudes and language that are shocking by today’s standards, the question that is once again raised by any tampering or sanitizing of the original source material is that of dangerous revisionism. These books can feel antiquated but their writing needs to be appreciated within context and seen as a reflection of past values.

As uncomfortable as some of the original words reflecting past attitudes can be, reading the original words and un-censored passages can help us understand regressive politics and the dangerous legacy of British colonialism with a modern eye.

The Christie edits feel like a further push by British publishers to whitewash the past – and in doing so, avoid modern conversations through redaction, conversations that would be valuable for a country which still wrestles with its island mentality and Empire nostalgia.

Novelist Joyce Carol Oates tweeted the news of the Agatha Christie edits, predicting the next target for the recent phenomenon of sensitivity readers would be French novelist and polemicist Louis-Ferdinand Céline.

Her followers had plenty to say on the matter:

Until the next inevitable news that further British publishing houses are seeking to cover up past sins to sell more books under the guise of sensitivity, readers can take solace in knowing that their original Dahls, Flemings and Christies are rapidly becoming collector’s items.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News