With an ageing population, Britain can't afford to keep neglecting entrepreneurs

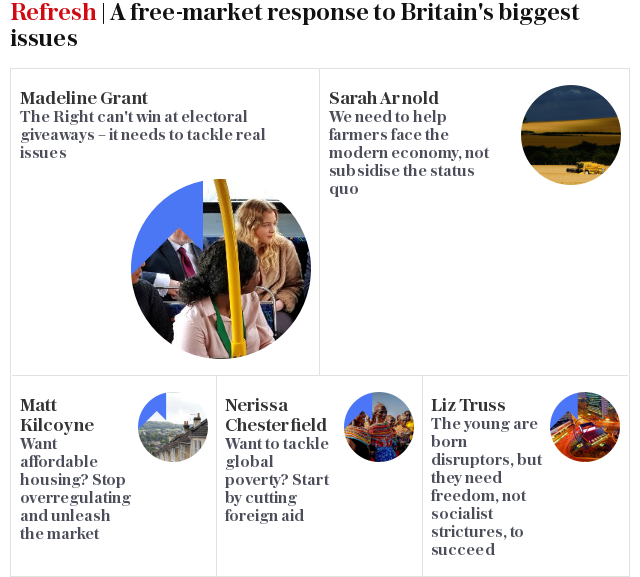

Welcome to Refresh – a series of comment pieces by young people, for young people, to provide a free-market response to Britain's biggest issues

It's a truism to say that we are living longer and having fewer children. On the one hand, that lifespans in developed countries more than doubled in the 20th century is cause for jubilation. On the other, short of pumping aphrodisiacs into the water system, we will struggle to avoid adverse effects from our ageing population.

The economic landscape will be transformed – consider, for example, that by 2020 a third of workers will be over 50.

An oft-overlooked consequence of this change is a drop in the share of the population best positioned to be successful entrepreneurs. While Harland David Sanders founded KFC at 65 and Facebook was conceived in a student dorm, most successful entrepreneurs will fall into the 25 to 49 age group.

Any later in life and entrepreneurship is more likely to take the form of self-employment or microbusinesses without growth ambition. Any sooner, and young guns may lack the funds, experience and network for fast growth. Steve Jobs may have founded Apple at 22, but it wasn't until two decades later that he was re-appointed its CEO and presided over a 100-fold increase in its market cap.

This wide age bracket has been brought to light in a group of essays from the Fraser Institute in partnership with The Entrepreneurs Network (UK), collectively entitled “Demographics and Entrepreneurship”.

Almost all industrialised countries have witnessed declines in entrepreneurship since 2001

It argues that 25-49-year-old founders typically possess a willingness to take risks, conjoined with the real-world business experience that increases the likelihood of success. Yet for the US, UK, Canada and Australia, there is a significant projected decline in this key entrepreneurial age group by 2065.

It may have taken until 2018 for the optimal age to be identified, but the ideal demographics peaked over two decades ago.

While 2017 was a record year for British startups, almost all industrialised countries have witnessed declines in entrepreneurship since 2001. In the US there was an 18.6 per cent drop in the rate of small business startups when comparing the six years before the Great Recession to the following six years. Australia and Canada also incurred declines.

It is hard to imagine that the UK can succeed in bucking a trend taking hold across the developed world.

If we are to tackle a long-term decline in entrepreneurship that is at least partially driven by demographics, we have little choice but to improve the environment in which entrepreneurs and businesses operate.

Perhaps the most important factor influencing entrepreneurial activity is the tax structure facing would-be entrepreneurs – and capital gains tax takes a hammering from the “Demographics and Entrepreneurship” authors.

Entrepreneurs risk their own capital and time in the hopes of profiting from a new business, typically accepting significant pay drops in the early stages so that earnings can be reinvested. In return, they expect to be compensated when the business matures. Yet 11 countries in the OECD have capital gains tax rates lower than the UK.

Starting and running a business came to be seen in Britain as a worthy and honourable occupation long before other European nations

We do offer Entrepreneurs' Relief – a tax break for those selling or giving away their business. It's an acceptable stopgap, but investors and entrepreneurs are two sides of the same coin.

Like taxes on interest income, inheritance and corporate profits, capital gains effectively taxes future consumption higher than current consumption, incentivising short-termism. Instead, our tax system must be neutral with respect to whether you spend money now or later, and must maximise the reward that entrepreneurs and investors receive from the sale of a business.

My colleagues have written about immigration at length – arguing that there is a strong economic case for allowing more, particularly highly-educated and highly-skilled, migrants into the UK. Immigrants account for a disproportionate share of successful business startups in developed countries and the US has been uniquely adept at attracting them – consider Elon Musk, Peter Thiel or Sergey Brin.

In the Brexit climate, we risk slipping further behind at a time when the competition couldn't be fiercer. If we want to maintain current startup levels, or to foster our own Google, the Government must change its tired narrative and take action on visa reform.

And finally, it matters what politicians and the public think of entrepreneurship.

As Art Carden and Deirdre McCloskey have brought to light, starting and running a business came to be seen in Britain as a worthy and honourable occupation long before other European nations, where the clergy and military held an exalted status. The economists explore the positive effects of a culture that values and promotes – rather than disparages – enterprise and entrepreneurship.

Anti-business rhetoric proselytised by Labour front-benchers and occasionally – alarmingly – appropriated by Tory members is all the more worrying in this context. If we can instead embrace buying low, selling high and innovation, say Carden and McCloskey, there is “no limit to what people can achieve”.

Annabel Denham is Editor at The Entrepreneurs Network

For more from Refresh, including debates, videos and events, join our Facebook group and follow us on Twitter @TeleRefresh

Yahoo News

Yahoo News