Ahmed Kathrada obituary

Ahmed Kathrada, who has died aged 87, was one of eight South African freedom fighters jailed for life in the 1964 Rivonia trial, along with Nelson Mandela. “Kathy”, as he was known, had been arrested the previous year at Liliesleaf Farm, Rivonia, in north Johannesburg, headquarters of the African National Congress’s armed struggle, and charged with plotting to overthrow the government.

Mandela recounted in his autobiography, Long Walk to Freedom (1994), that in court, “Kathy, in his sharp-witted testimony, denied committing acts of sabotage or inciting others to do so, but said he supported such acts if they advanced the struggle”. Kathrada refused to break ranks. It was the sort of response, together with the determination of Mandela and Walter Sisulu, another of the accused, that turned the tables on their prosecutors, putting the state in the dock by highlighting the brutalities of apartheid.

After the trial, when they had been flown to prison on Robben Island, George Bizos, one of their barristers, arrived to discuss the chance that Kathrada and another prisoner, Raymond Mhlaba, could have their sentences reduced on appeal. They refused, and spent more than 25 years in prison. The importance of this gesture for Kathrada was to show that the liberation struggle had support across the racial divide.

But as a non-African Asian – the white activist Dennis Goldberg served his sentence with other white prisoners in Pretoria Central – Kathrada was allowed to wear long trousers and socks with shoes. The black prisoners wore shorts and sandals without socks, to rub in the fact of their servitude. The Africans’ meals centred on samp, made from dried corn kernels, while Kathrada and mixed-race prisoners were given European-type cuisine.

In prison, Kathrada obtained four degrees through University of South Africa correspondence courses. Studies were banned when a copy of Mandela’s autobiography was dug up in the prison yard. Yet Robben Island itself became an informal “university”. When working in the limestone quarry, the inmates would discuss history and politics.

In 1982 Kathrada followed several of his co-defendants to Pollsmoor prison in the Cape Town suburb of Tokai. “I saw a child after 20 years,” he told an interviewer. “It was the worst deprivation, absence of children.” When, in 1989, a guard announced he had received a fax to say they were being transferred to Johannesburg prior to their release, “Our reaction was, ‘What is a fax?’”

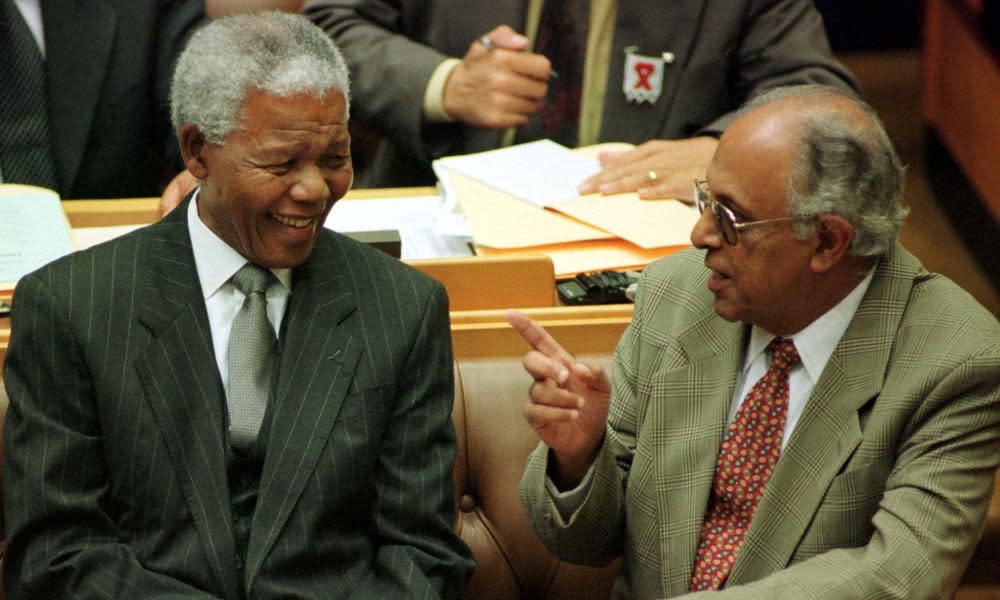

Kathrada was 60 when he was at last freed, in October 1989. After Mandela was elected president of South Africa in 1994, he appointed his close friend, by now an MP, his parliamentary counsellor in the first ANC government.

Born in the small Transvaal town of Schweizer-Reneke, Ahmed was the fourth of six children of Muslim emigrants from Surat in Gujarat, India. There being no Indian schools in the town, he moved to Johannesburg. There, influenced by the Transvaal Indian Congress, he entered the fray – the Indian community had been politicised by the activities of Mahatma Gandhi. He joined the Young Communist League aged 12, and was soon taking part in passive resistance campaigns.

Leaving the Indian high school at 17, he went to work for the Transvaal Passive Resistance Council, then engaged in a battle against the “ghetto” act (1946) that restricted Asian land ownership. The measure was enacted by the pre-apartheid government of General Jan Smuts, and Kathrada spent a month in jail in Durban for his pains.

His studies at the University of the Witwatersrand were interrupted in 1951 to lead a multiracial South African delegation to eastern European capitals. On his return home he enrolled in the gathering struggle against the implementation of the apartheid state. He was arrested for treason, together with 155 other resistance leaders from all race groups, but the trial petered out after four years. In December 1961 the opposition gave up peaceful protest and launched an armed struggle.

When Kathrada was “house arrested” in an attempt to cauterise his activities, he went underground, working for Umkhonto we Sizwe (Spear of the Nation), the ANC’s military wing. Among his feats was to organise the smuggling of Mandela across the border into British Bechuanaland (later Botswana) en route to a meeting of African leaders in Ethiopia. The armed struggle received a fatal blow with the arrest at Liliesleaf Farm. Mandela, already doing time on Robben Island for a “lesser” sentence, was flown in to join the arrested men on trial.

In later life, Kathrada chaired the Robben Island museum, preserving the prison as part of the country’s heritage. It was there that he launched the campaign to “free Marwan Barghouti and all Palestinian prisoners”. Soon after making the Hadj pilgrimage to Mecca in 1992, he left the Communist party. He wrote several books including No Bread for Mandela: Memoirs of Ahmed Kathrada, Prisoner No 468/64 (2010).

Last year he urged Jacob Zuma to resign, after the country’s highest court found the president had refused to pay back public money spent on upgrading his rural home. Yet after Kathrada’s death Zuma’s office ordered flags to be flown at half-mast and said South Africa had “lost a titan”.

One survivor of the dwindling group of liberation’s golden age, the retired archbishop Desmond Tutu, spoke of Kathrada’s “remarkable gentleness, modesty and steadfastness … a moral leader of the anti-apartheid movement”.

He is survived by his partner, Barbara Hogan, a minister in Mandela’s cabinet.

• Ahmed Mohamed Kathrada, political activist, born 21 August 1929; died 28 March 2017

Yahoo News

Yahoo News