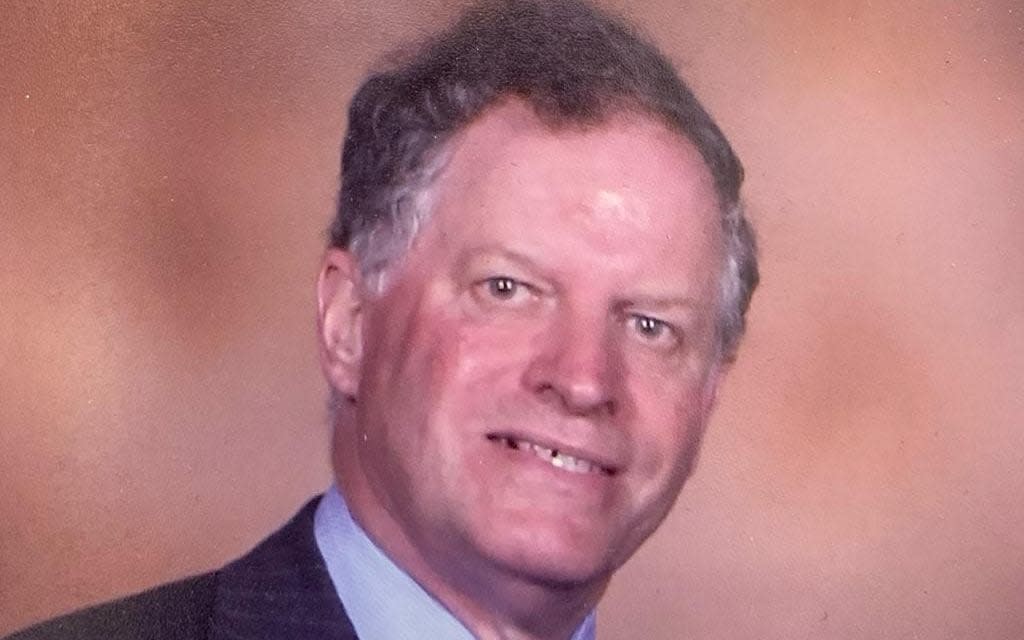

Alastair Macdonald, leading civil servant at the DTI who was in charge of IT and carried through the British Telecom privatisation – obituary

Alastair Macdonald, who has died aged 81, was for two decades a pivotal figure in the Department of Trade and Industry, assisting the infant IT sector in the early 1980s, organising the privatisation of British Telecom and finally overseeing the entire range of industrial policy as Director-General for Industry.

He worked closely with ministers in Conservative and Labour governments, striking up particularly strong rapports with Kenneth Baker, Norman Tebbit, Michael Heseltine and Peter Mandelson.

Diligent, hardworking, conscientious and discreet, Macdonald was respected as a man of probity. After entering Whitehall, for example, he was renowned for insisting on paying his half of the bill for lunch with a journalist out of his own pocket, rather than accepting entertainment on expenses.

Alastair John Peter Macdonald was born at Twickenham on August 11 1940, the eldest of three children of Ewen and Hettie Macdonald. His father was an engineer with a company making meters to control the flow of pressure in power stations.

From Wimbledon College, where the future economic commentator and FT colleague William Keegan became a lifelong friend, he went up to Trinity College, Oxford in 1959 to read Modern History. He was among the first undergraduate intake not previously to have done National Service.

Fascinated by newspapers, Macdonald became involved with the student magazine Isis, working alongside Richard Ingrams, Paul Foot, Willie Rushton and Andrew Osmond. These older colleagues, he recalled, “spoke about wanting to start a sort of satirical magazine like the French Le Canard enchaîné, and the term after they left, they started this strange little magazine which had the title Private Eye.”

That same term, Macdonald succeeded the future Arts Minister Grey Gowrie as editor of Isis. Graduating in 1962, he went into journalism, initially with The Spectator then after nine months moving to the FT as a reporter.

There, he joined “a team of young people whose job was to write a feature, probably once a week, about the prospects of a particular industry. You were obliged to seek out the players in the area you were writing about and interview them, and write up a 900-word piece about the prospects for that industry. That experience was actually almost like going to a business school for a year or two.”

Macdonald next spent a year in the FT’s Washington office as deputy to David Watt, returning in 1966 to become the paper’s features editor. While at the FT, he invested with a group of colleagues in a greyhound named Gurrane Jet, which ran with conspicuous lack of success at the old Wimbledon Stadium.

While in Washington, British embassy staff encouraged him to consider a move to the Civil Service, and in 1968 he sat and passed the entry exam. Breaking the news to his colleagues, he explained: “Power is where power lies.”

He began as an assistant principal in the Department of Economic Affairs, which the next year was absorbed into the Treasury. In 1971 he began his long association with the DTI; his first assignment – which he particularly enjoyed – was as secretary to Lord Devlin’s inquiry into how business and industry could be better represented, commissioned by the Confederation of British Industry and the Association of British Chambers of Commerce.

In 1982, Macdonald, by then an under-secretary, was put in charge of the fast-developing field of IT, working with an enthusiastic and stimulating minister in Baker. He was not that technical himself, but the appointment was a success.

It was IT Year, and one government initiative was the Micros in Schools scheme, which, he recalled, “opened the eyes of schoolchildren, and their parents, to what was actually happening in IT through playing games on the BBC Micro”.

The DTI then had two aims for the IT industry: to help relatively small British companies build themselves up to become internationally competitive – something that proved hard to achieve – and to keep afloat the nation’s flagship company, ICL, which would eventually merge with Fujitsu.

Macdonald was particularly involved in working up the Alvey Project, the Government’s response to Japan’s Fifth Generation initiative in computing, which aimed to develop a range of pre-competitive technologies in concert with academia and industry. He reckoned that Alvey proved valuable in getting teams from the three sectors used to working together, but produced few tangible commercial benefits.

In 1984 he moved to head the DTI’s telecommunications division, to prepare in particular for the BT privatisation. This involved getting the Telecoms Bill through Parliament, negotiating the licence with BT setting out exactly what the company could do, and organising the international stock flotation.

“Every Monday morning I would chair a meeting of Kleinwort Benson and Linklaters, our lawyers, the Treasury, and our own team at DTI, and thrash through what had to be done, where we had got to on a thousand issues or so. We were monitored closely by Norman Tebbit, who took a very keen interest.”

Despite initial scepticism inside and outside government that the project could be carried through, the flotation was successful – and the biggest the City of London had ever seen.

From 1990 to 1992, Macdonald was seconded to the MoD as Deputy Under Secretary of State (Defence Procurement). He returned to the DTI as Director-General (Industry), holding this post for eight years until his retirement in 2000.

For the first three, his secretary of state was Heseltine. “One felt he had wanted to have the job of being the Secretary of State for Trade and Industry for a long time,” Macdonald recalled. “He was particularly anxious that civil servants should be close to industrialists, should be listening to them, and should be influenced by them and should report back to ministers the feeling of industry.”

Macdonald served from 2001 to 2007 as a Civil Service Commissioner, and in 2000-01 was president of BCS, the Chartered Institute for IT. He helped to replace its 50-strong decision-making Council with a more manageable Trustee Board, the Council taking up an advisory role.

In retirement he was also a member of the Design Council and a trustee of Chatham Historic Dockyard, while in private his greatest pleasure was tutoring his grandchildren in chess and cricket. He was a devotee of opera and of the works of Anthony Powell, and he keenly followed goings-on in Westminster.

He was appointed CB in 1989.

Alastair Macdonald married, in 1969, Jane Morris. She survives him, with their son and two daughters.

Alastair Macdonald, born August 11 1940, died January 9 2022

Yahoo News

Yahoo News