Allan Stephenson, British composer, conductor and cellist who became a leading figure on the South African music scene – obituary

Allan Stephenson, who has died aged 71, was a British-born cellist, composer and conductor who made his name in South Africa; among more than 110 works he contributed the first act of The Mandela Trilogy, an opera by three composers in which his contribution explored Nelson Mandela’s early years in rural Transkei and his initiation into adulthood.

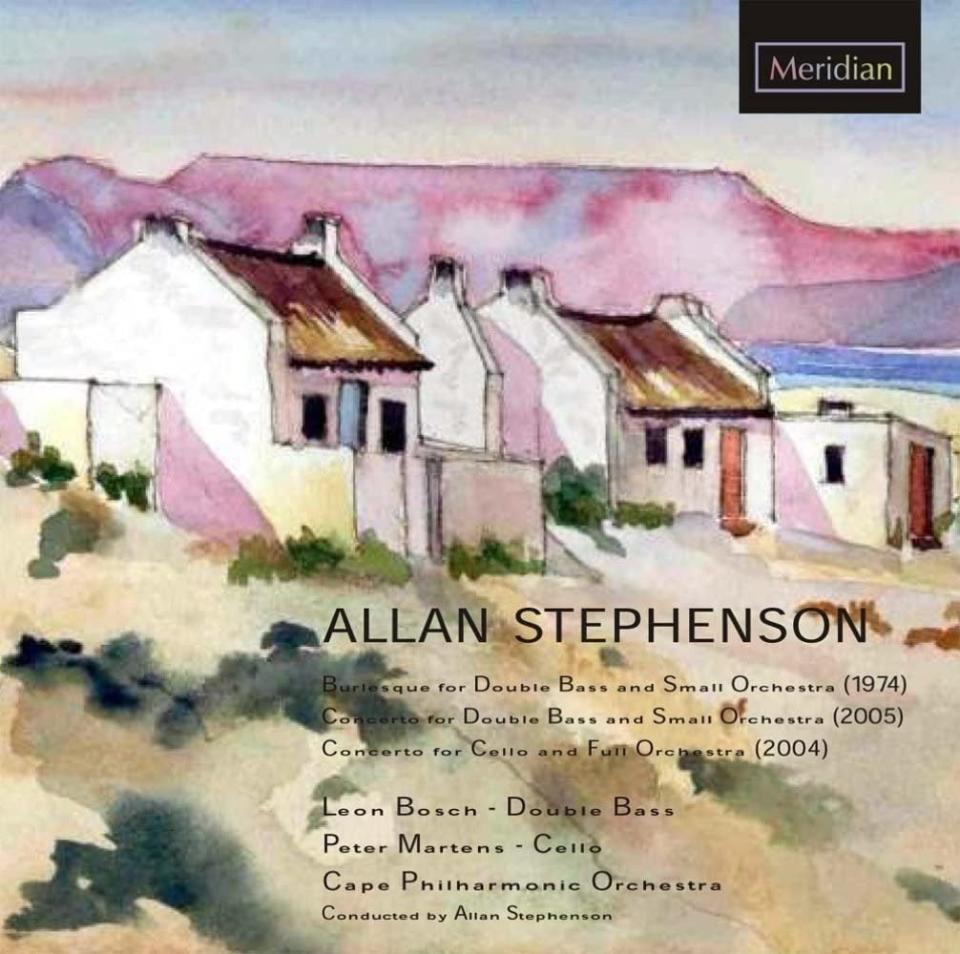

Stephenson was responsible for the South African premiere of several major European pieces, notably Nielsen’s Symphony No 4, the “Inextinguishable”. He was also behind the first classical music CD to be made in South Africa, a recording of his Concertino Pastorale for Clarinet.

His own work involved collaborating with both international soloists and South African musicians, notably Thomas Rajna, Olivier de Groote and Hugh Masekela. However, he was wary of writing “Africanised” music, saying that that was something he preferred to leave to native composers, whose music is in their roots.

“I can’t write music that is not going to sound English, even if I force myself,” he said. “Why would I do that when I feel I have my own style? It just would not be authentic. So I just keep writing music for myself and that keeps me in work.”

Allan Stephenson was born in Wallasey, on the Wirral, on December 15 1949. His parents were not musicians but supported his interest. He began studying piano aged seven, and at 13 came across an old cello in a school storage room that he quickly learnt to play; within a year he was a member of the Merseyside Youth Orchestra. He also sang in the school choir and learnt the trombone and tuba.

While studying cello at the Royal Manchester College of Music he picked up freelance work with the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra, where his teacher was principal cellist. In 1972 Hugo Rignold, the orchestra’s former conductor, asked the teacher if he could suggest a cellist for the Cape Town Symphony Orchestra, where Rignold was working.

“Although I was already playing for the RLPO, the orchestra’s management did tell me I needed more experience so I should go somewhere and come back to them in a few years’ time,” Stephenson recalled. “So the Cape Town job was a great way to achieve that.”

He was auditioned in London in November 1972 and two months later flew to South Africa, where he was roped into part-time teaching at the South African College of Music, part of the University of Cape Town. When the cello lecturer died suddenly, Stephenson took on extra students on top of his orchestral post. “I couldn’t manage it all, so I suggested that they hire my fiancée,” he said.

Meanwhile, he had made his conducting debut in the world premiere of his Symphony No 1, a work that he began writing on the pier at Llandudno in North Wales and completed in Cape Town. Like much of his music it was intended to please the listener while also challenging the performer. “My theory is that if I can’t stand the noise my music makes, how can I expect anybody else to?” he reasoned.

The Cape Town Symphony Orchestra’s demise in 1997 provided other opportunities: he founded the Cape Town Chamber Orchestra, conducted the string ensemble I Musicanti and made musical arrangements for Cape Town City Ballet, including Offenbach’s The Tales of Hoffmann. Much of his own music is for chamber ensemble, though he also wrote Animals, an opera based on George Orwell’s Animal Farm, and some useful choral works.

Allan Stephenson his survived by his wife, Christine, whom he married in 1973, a few days after she flew out to help with his teaching load in Cape Town.

Allan Stephenson, born December 15 1949, died August 2 2021

Yahoo News

Yahoo News