Allen v Farrow is pure PR. Why else would it omit so much?

“HBO Doc About Woody Allen & Mia Farrow Ignores Mia’s 3 Dead Kids, Her Child Molester Brother, Other Family Tragedies” was the headline on one US showbiz site, above its review of the four-part documentary, Allen v Farrow, about the continuing battle between Woody Allen and Mia Farrow, now entering its fourth decade. But this review was very much an outlier. In the vast main, reaction to the strongly anti-Allen series has been overwhelmingly positive, with Buzzfeed describing it as a “nuanced reckoning” and Entertainment Weekly comparing it to the recent documentaries about Michael Jackson and Jeffrey Epstein. This reaction is more of a reflection of the public’s feelings towards Allen – particularly in the US – than of the documentary, which sets itself up as an investigation but much more resembles PR, as biased and partial as a political candidate’s advert vilifying an opponent in election season.

Related: Allen v Farrow review – effective docuseries on allegations of abuse

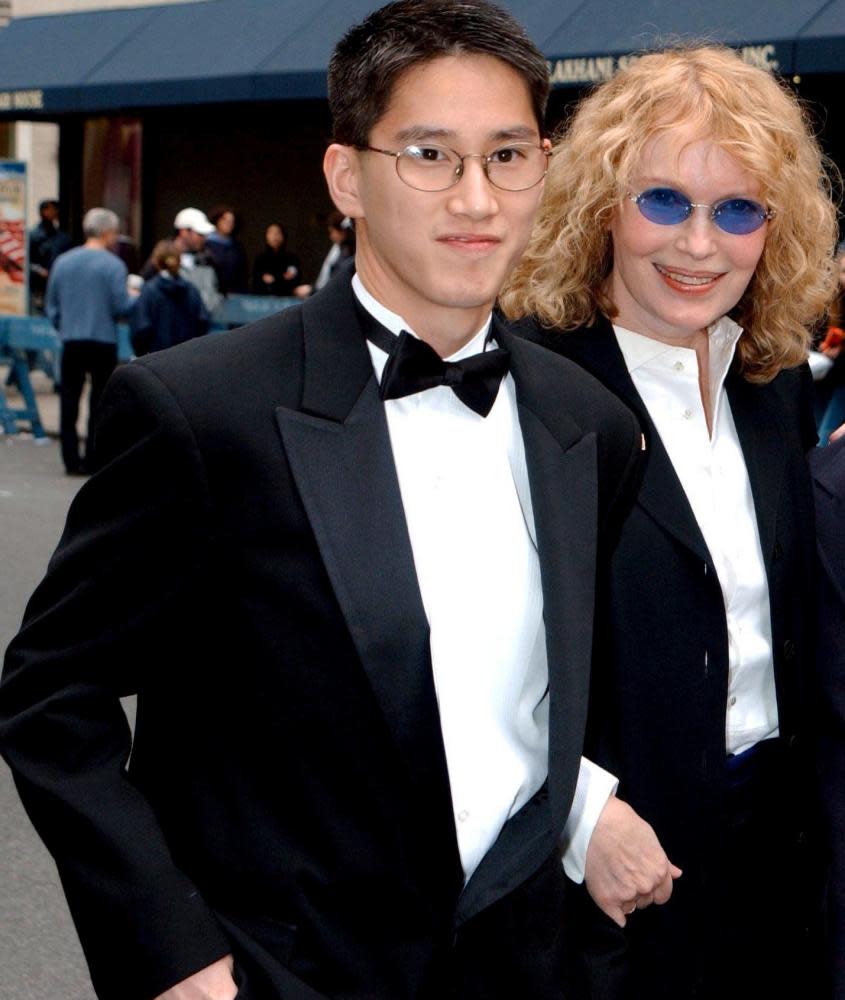

A recap for those who have managed to stay ignorant of this enduring family drama or, more likely, forgotten the details over time, something the documentary is heavily counting on. Back in 1992, Allen, then 57, admitted he was having an affair with Soon-Yi Previn, 21, the adopted daughter of his longterm partner, Farrow, with whom he had two adopted children – Dylan and Moses – and one biological child, Ronan (known then as Satchel). Several months after that, at the height of their viciously acrimonious break up, Farrow accused Allen of molesting Dylan, who was then seven, one afternoon while she was out of the house. Doctors examined Dylan and found no evidence of abuse. Allen was investigated by the Yale New Haven Hospital’s sexual abuse clinic which concluded: “It is our opinion that Dylan was not sexually molested by Mr Allen.” He was also investigated by New York State’s Department of Social Services, which wrote: “No credible evidence was found that the child named in this report has been abused or maltreated.”

In Allen v Farrow, directors Amy Ziering and Kirby Dick play on two strong currents in today’s popular culture: first, the enormous appetite for true crime documentaries, and second, a re-evaluation of past wrongs, looking back at a distant time when people were insufficiently evolved to understand social justice. These two elements struggle to work together because unless a true crime documentary has a smoking gun – such as Robert Durst’s confession in The Jinx – the appeal of the genre lies in its ambiguity, allowing the audience to play detective, such as with the podcast Serial, or Netflix’s Making a Murderer.

In this regard, the Allen case is actually a perfect subject for a true crime documentary, given that the case has always had multiple – to put it mildly – ambiguities, many of which have now been forgotten. But Ziering and Dick don’t seem to have any interest in that, because their focus is on social justice. They have been criticised in the past for “putting advocacy ahead of accuracy” in their 2015 documentary about campus rape, Hunting Ground, which used discredited data.

The Guardian sent a detailed list of Allen v Farrow’s omissions to Ziering and Dick. Instead of responding to them individually, they sent this response, which they requested be printed in full:

The film-makers behind Allen v Farrow meticulously examined tens of thousands of pages of documents, including court transcripts, police reports, eyewitness testimonies and child welfare records. We spoke with dozens of persons involved with the case who had first-hand knowledge of the events and whose accounts could be independently corroborated. Allen v Farrow is a complete, thorough and accurate presentation of the facts.

Dick has described himself in the past as “an activist and a film-maker”, and activism can be the opposite of journalism, because rather than asking questions to find the truth, the conclusion looks pre-ordained from the start, with inconvenient facts getting pushed aside – and there are many inconvenient facts when it comes to Allen.

Back in the early 90s, people were more shocked by his relationship with Soon-Yi than they were by the soon scotched allegation of child molestation. But ever since 2014, when Dylan and Ronan started to speak out publicly against their father, the public and media, anxious not to be on the wrong side of history again, have focused on the molestation claim, and Allen is now widely agreed to be, to use the currently popular term, “problematic”. “It’s time to ask some hard questions,” Ronan wrote in a 2016 article, comparing his father to Bill Cosby.

One of those hard questions, which Ziering and Dick work very hard not to answer, could be: is it really reasonable to mention Allen alongside Cosby – and Jackson, Epstein, Harvey Weinstein and other celebrity predators – when the latter have all been charged or convicted of multiple crimes going back decades, and Allen was accused of one incident and not only never convicted but never even charged, and there has never been a hint of scandal around him since? Given how much sterling work Ronan has done in exposing Weinstein and other compulsive predators, you’d think he might ask himself that question, but apparently not. Ziering and Dick seem similarly certain of their case, but it’s hard to believe they have so much faith in it when they omit so many relevant details.

For example, despite the documentary’s claim to go beyond “the tip of the iceberg”, it never finds time to get into the testimonies of Monica Thompson, Dylan’s nanny, who was very much on the surface of the iceberg. Initially Thompson told police that Farrow was “a good mother,” but then retracted it, saying she felt she had to say it or “I would lose my job.” She then gave two sworn affidavits that Farrow had tried to force her into supporting the molestation charge, and said that Allen “was always the better parent and all the things Farrow is saying about him are not true”.

It does, however, have the space to include a New York Times reporter mournfully announcing that he can never watch a Woody Allen film again, which is truly a game-changer of a revelation. The series works very hard to discredit the Yale New Haven investigation and the Farrows dismiss the report’s finding that Dylan had “trouble distinguishing between fantasy and reality”, putting this down to strangers not understanding Dylan’s references. The film-makers don’t include the testimony from Dylan’s own therapist at the time, Dr Nancy Schulz, who said that Farrow and Allen first asked her to treat Dylan because the child “lived in her own fantasy world”.

Dr Susan Coates, another one of the family’s many psychologists, testified that a 1990 evaluation found that Dylan was easily “taken over by fantasy”, even when asked to describe a tree.

The series’ opening titles are in a white-on-black font that bears a queasy resemblance to the one Allen uses for his movies, as if the film-makers are proud of their refusal, or inability, to look beyond Allen’s public persona. (Ziering and Dick break the shocking news that Manhattan – arguably Allen’s most famous film – is about a relationship between a teenager and a middle-aged man.) Allen himself is not in the documentary – he allegedly declined to be interviewed; nor is anyone who supports him. Despite the title’s suggestion of balance, this is very much the Farrows’ show with Farrow interviewed in an often glowing golden light, and her children Dylan, Ronan, Fletcher Previn and Daisy Previn, backing up all claims that Farrow was a saint and Allen seemingly nice but actually, it turned out, scum. Ziering and Dick know they don’t have much in the way of new material, aside from some never-before-seen Farrow-Allen family videos. Alas, these videos of Allen playing in the pool with his young children are disappointingly non-damning, and so the film-makers overlay them with mournful, ominous music. “[Dylan] went from being effervescent to having a withdrawn quality,” Ronan says, recalling a period when he was – at most – four years old.

The video of seven-year-old Dylan telling her mother that her father touched her on her “privates” is undeniably painful to watch, but it’s never been in question whether she said this. The question is was she coached to say it: the Yale New Haven team and, later, Moses Farrow say she was; the Farrows and all of the talking heads Ziering and Dick assemble together say she wasn’t. It would be ludicrous for outsiders to say who is right, but it’s interesting how the series glides over the detail – reported at the time by a journalist sympathetic to the Farrows – that when Dylan was asked by a doctor where her father touched her she initially “pointed to her shoulder”.

Much is made of the quote by Coates when she described Allen’s relationship with Dylan as “inappropriately intense” (less is made of her follow up that it was “not sexual”). But there are no references to Coates’ fears for Allen’s “safety” after Farrow discovered the affair with Soon-Yi, due to her “escalating rage”.

During the period after the breakup, Farrow gave Allen a Valentine’s Day card that featured a photo of all the children, which she stabbed with pins and scissors. In a 1992 interview, Allen said that Farrow told him: “You took away my daughter, and I’m gonna take away yours.”

When Farrow later told Coates that Dylan said Allen had molested her, she sounded, for the first time since the discovery of the affair, “very calm”. “I was puzzled. I did not understand her calm,” Coates said.

Related: Woody Allen denies claims in Allen v Farrow HBO documentary

The problem with bias is that it undermines everything you say, however interesting or credible. Of greatest significance to obsessives about this case is the revelation in the documentary that, in their map of the house, the Connecticut State Police drew a train track in the attic space where Dylan says her father molested her. Since 2014, Dylan has said she stared at an electric train “as it traveled in its circle around the track” while her father abused her, promising, she has said, that she would be “a star in his movies”.

Moses and Allen have written that there was no electric train in the attic, and Allen has said that the attic allegation was inspired by a song by Dory Previn, whose husband André left her for Mia in 1970. With My Daddy in the Attic is about incest and molestation and features lyrics such as “Door closed on Mama … / With my Daddy in the attic / That is where my dark attraction lies.” (This song appears on the same album as Dory Previn’s notorious song, Beware Young Girls, which was about Farrow’s affair with André.)

The police drawing suggests Dylan was telling the truth. However, Robert B Weide, a director and friend of Allen, has blogged in response to the series that a nanny in the household testified at the time that there was a train set kept up there – not a small electric one, but a chunky plastic train the children would sit on and ride. So in other words, everyone is right and also wrong: a train was stored up there, as Dylan said, but not an electric one that could have circled the track, as Moses and Allen said. It’s a point that sums up so many of the grey areas to this case, and yet another one that Ziering and Dick denote instead as black and white.

Ziering and Dick tell the story – which was reported at the time – about New York City welfare case worker Paul Williams, who was part of an investigation into Allen, and who claimed that he had been urged by his superiors to find the charges “unfounded”. When he refused – and we see him telling reporters he “believes the kid” – he was taken off the case. Ziering and Dick strongly imply that something dodgy happened here, but instead of finding any actual evidence, the film-makers air entirely unproven theories that Allen was being protected by the City of New York, even perhaps by then-mayor David Dinkins, because “he made his movies in New York and that brought millions of dollars to New York City”, theorises Farrow. (Sadly, if perhaps conveniently, Dinkins is now dead and so can’t comment on this.) At the time of the investigation, Allen’s lawyer, Elkan Abramowitz, said that Williams was removed from the case because when he interviewed people “he acted in a rude fashion and appeared to be biased”. Now, it wouldn’t be hard to style this as shady lawyer obfuscation, so why don’t Ziering and Dick include this counter-argument in the film? Because counter-arguments are of little interest to Ziering and Dick.

Rich and powerful men do and did get away with a lot – this is a given. But the documentary’s contention that “if you are a powerful celebrity male, you are nearly impossible to prosecute” is undermined by its frequent comparisons between Allen and male celebrities – Weinstein, Cosby, Polanski, and so on – who have, in fact, all been prosecuted. Why not Allen, the documentary asks? Well, there might be some good reasons for that which have nothing to do with Mayor Dinkins.

Contrary to longstanding rumours that Allen refused to take a lie-detector test administered by the Connecticut State Police, he was never asked to take one. Instead, he took one administered by Paul Minor, who for many years ran the polygraph division of the FBI. He passed.

Similarly, the image the series draws of Allen as terrifyingly powerful, his thumb drilling down on the scales of justice, is contradicted by the fact that Judge Elliott Wilk ruled against him in the custody case, which was going on during the scandal, when Allen sued for custody of Ronan, Dylan and Moses, and lost. Farrow, on the other hand, gave her next adopted child, Thaddeus, the middle name Wilk, as a sign of gratitude to the judge.

Thaddeus later died from what Moses has called suicide, while another child adopted by Farrow, named Tam, died by what Moses claims is suicide and Farrow says was a heart ailment. The film mentions neither – nor a further adopted child, Lark, who died in poverty from an Aids-related illness. There is a similar silence in the section on Mia’s family about her brother, John Villiers-Farrow, a convicted paedophile.

Then there’s Soon-Yi. The documentary, and the Farrow family, can’t decide whether she’s an evil seductress who must be shunned, or a tragic victim of a sexual predator, as they claim Allen to be. A friend of the family says in the documentary that Allen only said he “loves” Soon-Yi in a 1992 press conference in order to distract from the molestation charge; no one in the entire documentary points out that Allen and Soon-Yi have now been together for almost 25 years, which suggests their relationship – as distasteful as it was at first – is clearly more than a smokescreen, and now looks close to conventional.

After the affair was discovered, Daisy Previn says in the documentary that she told her sister: “Mom will forgive you.” Farrow insists she “never blamed” Soon-Yi, although she admits she did hit her when she caught her talking on the phone to Allen. Soon-Yi and Moses have written that she did a lot more, claiming Farrow was physically abusive to them and favoured her biological children over her adopted ones. These allegations are firmly denied by Dylan, Ronan and Fletcher, but Thompson confirmed them in her 1993 testimony.

“The things [Moses] accuses [Farrow] of are ludicrous,” says Dylan. In almost the next breath, she complains that anyone who doubts her allegations against her father is denying her the right “to describe my own experiences”. Some children’s experiences are more equal than others.

Ziering and Dick don’t know what happened between Dylan and her father. Neither do I and neither, perhaps, does anyone at this point, as repeated retellings take the place of real memory. Braver and better film-makers would drill down into how historical truth can change over time, and how two people can look at one image and see very different things. Was Allen’s tendency to follow Dylan anxiously around the playground creepy, as one of Farrow’s friends alleges, or was it the behaviour of a famously neurotic man experiencing fatherhood for the first time? And if Farrow’s friend Carly Simon saw Allen “eroding [Farrow’s] self-esteem”, as she claims in the documentary, why, in 1992, did she write a song, titled Love of My Life, which included the lyric, “I love … Woody Allen”? Simon eventually changed the line – although not until 2007 – but a journalist would have asked her about this. Ziering and Dick did not.

Related: Moses Farrow: ‘I’d be very happy to take my father’s surname’

The only real question this documentary poses is why it exists at all. Allen’s guilt – certainly in his home country – is already widely assumed: his name is cited alongside Weinstein’s and Cosby’s in newspapers; Amazon reneged on a four-movie deal with him when his public denials of wrongdoing were deemed too problematic, and cancelled the US release of his last film, A Rainy Day in New York; his original publisher binned his memoir last year after lobbying from the Farrows, a detail that is also omitted in the documentary, despite heavy usage of the audiobook of Allen’s memoir in lieu of an actual interview with him.

“For the past 20 years he was able to run amok,” Dylan complains, and it’s true, he was. And he will continue to do so because he was investigated, twice, and no wrongdoing was found, which is exactly what this documentary finds, too. There is an understandable and admirable fear among the public to not repeat the mistakes of the past: to not disbelieve women, to not downplay the trauma of sexual abuse. But not all allegations are the same, and some cases are too complex to fit into the black-and-white template mindset of activism. In the third episode, Farrow recounts a conversation she had with Allen in which he allegedly said to her: “It doesn’t matter what’s true – it matters what people believe.” She tells this as proof of Allen’s coldness, his cruelty, but he was right. The definitive truth will never be known about this case. But people will always believe what they want.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News