Alzheimer's link to herpes virus in brain, say scientists

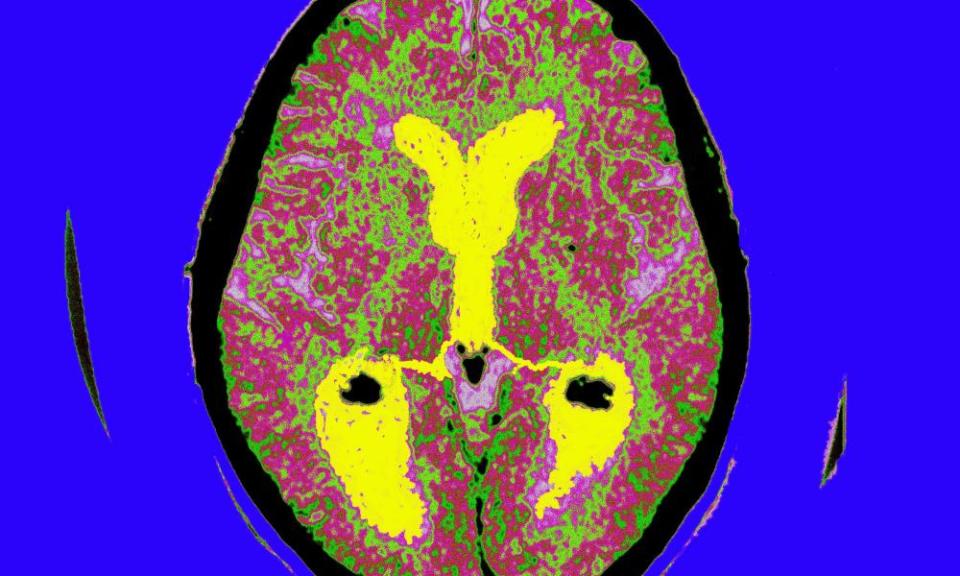

The presence of viruses in the brain has been linked to Alzheimer’s disease in research that challenges conventional theories about the onset of dementia.

The results, based on tests of brain tissue from nearly 1,000 people, found that two strains of herpes virus were far more abundant in the brains of those with early-stage Alzheimer’s than in healthy controls. However, scientists are divided on whether viruses are likely to be an active trigger, or whether the brains of people already on the path towards Alzheimer’s are simply more vulnerable to infection.

“The viral genomes were detectable in about 30% of Alzheimer’s brains and virtually undetectable in the control group,” said Sam Gandy, professor of neurology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York and a co-author of the study.

The study also suggested that the presence of the herpes viruses in the brain could influence or control the activity of various genes linked to an increased risk of Alzheimer’s.

The scientists did not set out to look for a link between viruses and dementia. Instead they were hoping to pinpoint genes that were unusually active in the brains of people with the earliest stage of Alzheimer’s. But when they studied brain tissue, comparing people with early-stage Alzheimer’s and healthy controls, the most striking differences in gene activity were not found in human genes, but in genes belonging to two herpes virus strains, HHV6A and HHV7. And the abundance of the viruses correlated with clinical dementia scores of the donors.

“We didn’t go looking for viruses, but viruses sort of screamed out at us,” said Ben Readhead, assistant professor at Arizona State University-Banner Neurodegenerative Disease Research Center and lead author.

Gandy said the team were initially “surprised and sceptical” about the results, based on brain tissue from the Mount Sinai Brain bank, and so repeated the study using two further brain banks – in total 622 brains with signs of Alzheimer’s and 322 healthy control brains – and detected the very same genes. “We’ve tried to be conservative in our interpretation and replicated the results in three different brain banks, but we have to at least recognise that these diseased brains are carrying these viral genomes,” he added.

The scientists could not prove whether viruses actively contribute to the onset of disease, but they discovered a plausible mechanism for how this could happen. Some of the herpes genes were found to be boosting the activity of several known Alzheimer’s genes.

David Reynolds, chief scientific officer of Alzheimer’s Research UK, said this element was significant. “Previous studies have suggested that viruses might be linked with Alzheimer’s, but this detailed analysis of human brain tissue takes this research further, indicating a relationship between the viruses and the activity of genes involved in Alzheimer’s, as well as brain changes, molecular signals, and symptoms associated with the disease,” he said.

However, others were more sceptical. Prof John Hardy, a geneticist at University College London, said: “There are some families with mutations in specific genes who always get this disease. It’s difficult to square that with a viral aetiology. I’d urge an extremely cautious interpretation of these results.”

The viruses highlighted are not the same as those that cause cold sores, but much more common forms of herpes that nearly everyone carries and which don’t typically cause any problems. The study in no way suggests that Alzheimer’s disease is contagious or can be passed from person to person like a virus – or that having cold sores increases a person’s risk of dementia.

There are currently 850,000 people living with dementia in Britain, and the number is projected to rise to a million by 2025 and 2 million by 2050. But despite hundreds of drug trials during the past decade, an effective treatment has not yet emerged.

“While these findings do potentially open the door for new treatment options to explore in a disease where we’ve had hundreds of failed trials, they don’t change anything that we know about the risk and susceptibility of Alzheimer’s disease or our ability to treat it today,” said Gandy.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News