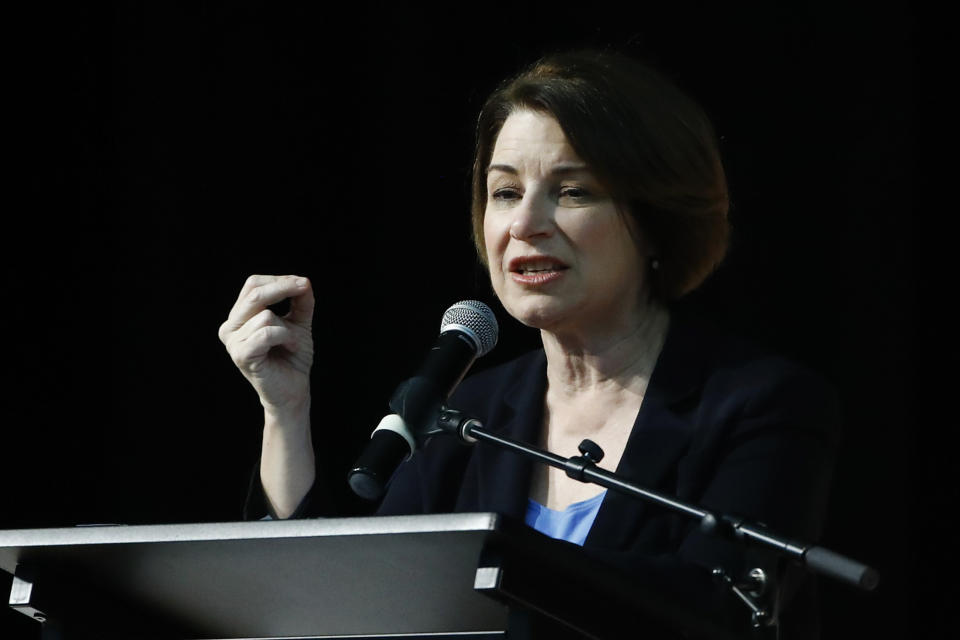

Amy Klobuchar needs black voters, but some feel 'peripheral'

MINNEAPOLIS (AP) — It took several weeks and about two dozen emails before Amy Klobuchar agreed to sit down with the president of the progressive racial justice organization Color of Change for his videotaped podcast on the 2020 presidential race, just as almost every other candidate has done. The Minnesota senator's campaign asked Rashad Robinson to travel to Washington and book a conference room near the Capitol for the taping.

But the day before — after Robinson and four staff members had traveled from New York and paid for a conference room at a Washington hotel — Klobuchar canceled. Instead, the senator spent Jan. 10 in Iowa, campaigning. The interview eventually was rescheduled for March 20 — after more than two dozen states will have voted.

The snub sent a message, Robinson said, that the former prosecutor and three-term senator from an overwhelmingly white state didn't care much about engaging on issues important to many black voters.

It's not the first time Klobuchar has faced that charge — black activists and community leaders in Minnesota have described her as indifferent or unfocused on their priorities, particularly those related to discrimination in the criminal justice system.

Now, as Klobuchar struggles to compete for the Democratic presidential nomination, her relationship with African American voters, and her lack of familiarity to them, could be her downfall. Next up to vote is South Carolina, where African Americans make up about two-thirds of Democratic primary voters, followed by March 3 Super Tuesday contests where states with significant African American populations including North Carolina and Alabama will weigh in.

Several polls show Klobuchar with single-digit support from black voters nationally and in South Carolina. A recent NBC/Wall Street Journal poll found about one-third of black voters said they didn't know Klobuchar's name.

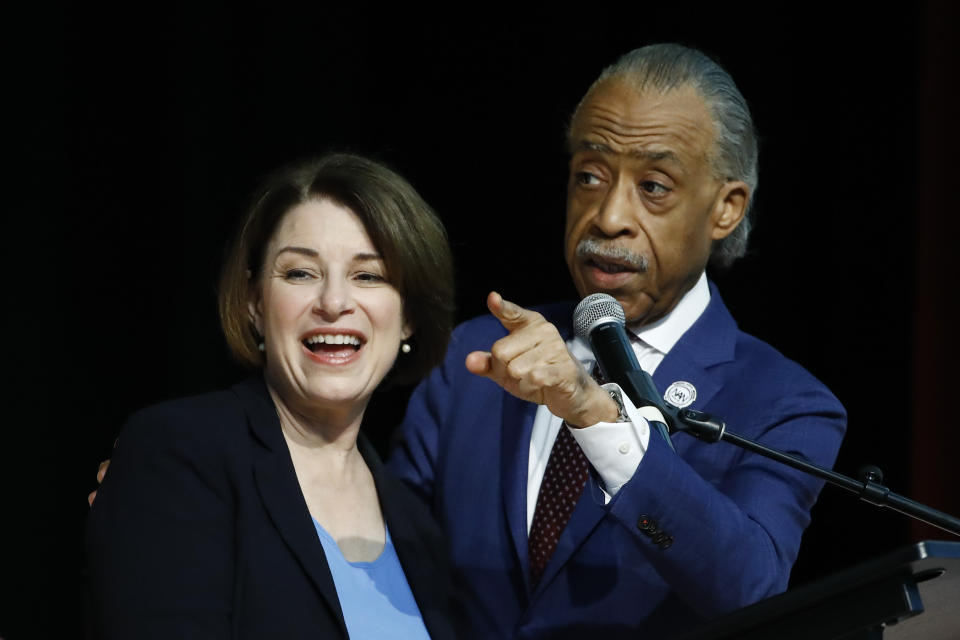

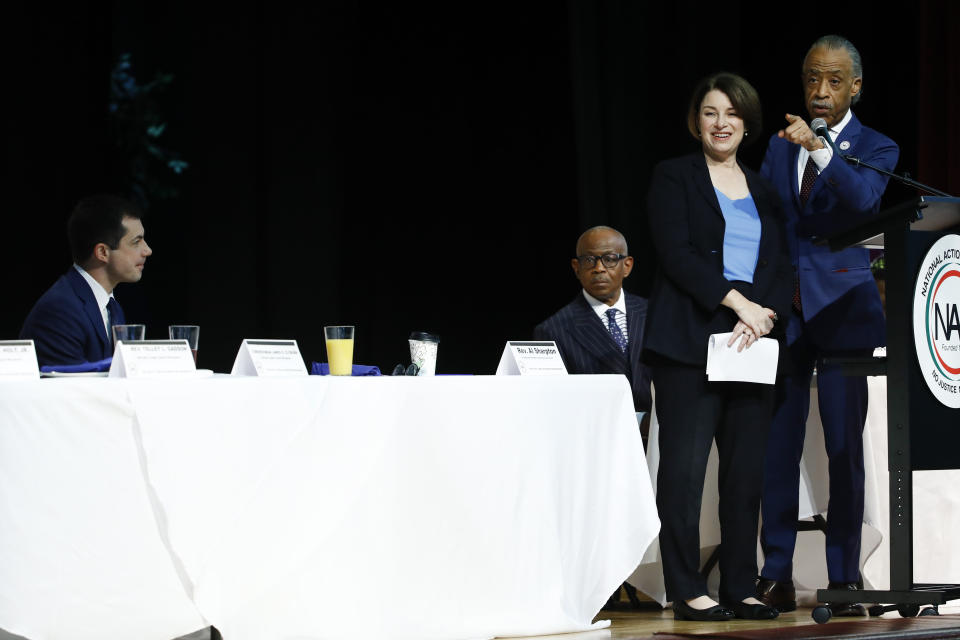

Klobuchar says her low poll numbers indicate African American voters still need to get to know her and she intends to “earn" black voters' support. On Wednesday, she was politely received at a ministers’ breakfast sponsored by the Rev. Al Sharpton’s National Action Network in North Charleston, South Carolina. But her remarks, which included a nod to “enormous racism in our criminal justice system,” didn’t get the same level of applause that rival Pete Buttigieg did as he acknowledged that he lacked the “lived experience” of the black voters he was addressing.

Klobuchar has taken steps to introduce herself to voters and hear from them. She held a voting rights roundtable in Atlanta in the first few weeks of her campaign and attended an NAACP convention in Detroit and a breakfast with the Arkansas Democratic Black Caucus in Little Rock. But her spending on staff and ads in South Carolina, where her campaign says she has a team of about 25, is minuscule compared with rival campaigns.

Some who know Klobuchar best say African American voters are right to be concerned about her commitment to them. Activists in Minnesota say their concerns stretch back to the late 1990s and early 2000s, when she was the lead prosecutor in Minnesota's largest county.

Nekima Levy Armstrong, a civil rights attorney and activist, said that she and others raised concerns about Klobuchar's tough-on-crime approach as prosecutor and her unwillingness to prosecute police officers for shootings — both of which disproportionately affected African American residents — but that Klobuchar didn't seem interested. The distrust has only deepened since an Associated Press investigation questioned Klobuchar's handling of a murder case that sent a black teen to prison for life after a police investigation that some say was flawed.

“It’s as if the issues that impact the African American community are peripheral to her," Levy Armstrong said. "Her focus has been mainly catering to mainstream, rural, white Minnesotans.”

Klobuchar's main argument as she seeks the Democratic nomination is a record of winning across Minnesota — particularly in conservative rural places — that she says she can replicate in the Midwest battleground to beat President Donald Trump. But Klobuchar has never competed in a race in which African Americans made up nearly as large a percentage of voters as she faces in the primaries ahead.

Minnesota's population is about 7% black, and Hennepin County, home to Minneapolis and where she won her first elected office, was about 10% black in 2000, when she was the county prosecutor. She finished sixth in Nevada on Saturday, after coming in fifth in Iowa and third in New Hampshire — both states with very small African American populations.

Klobuchar has defended her record as a prosecutor, saying she pushed for things like drug courts and restorative justice to divert offenders from prison. In the Senate, she has pushed to restore the Voting Rights Act to fight discrimination at polling places and improve the retention of minority teachers. She's campaigned on an “economic justice” plan that includes more money for schools and to address health care disparities and calls for ending housing discrimination.

Ken Foxworth, a Minneapolis educator and activist, credits Klobuchar for supporting a program aimed at improving the high school graduation rate for African American men. Almost 400 young men went through the program, and nearly half went on to attend some type of post-secondary school, he said.

The 62-year-old also likes Klobuchar's record on issues like mental health and infrastructure and said people who view her only through the lens of her tough-on-crime approach aren't considering the full picture.

“Yeah, she was hard on that,” he said. “But look at what she did for those other 300, 400 black men. She changed their lives, too.”

Brian Herron, pastor of Zion Baptist Church on Minneapolis’ north side, said that he believes Klobuchar always has tried to be fair but that her record on issues with the police and young African American men “caused an angst within the community.”

More recently, Herron said, people were looking for a better response than she's provided in the case of Myon Burrell, who was 16 when he was arrested in the 2002 stray-bullet shooting death of an 11-year-old girl.

Burrell was convicted after a trial that relied on a teen rival's account. The AP investigation found there were no other eye witnesses and no gun, fingerprints or DNA. The now 33-year-old has maintained his innocence, and his co-defendants say he wasn't present when the shooting occurred.

Klobuchar responded by calling on prosecutors to take another look at the case. But that wasn't enough for some prominent African American leaders in Minnesota.

“If Myon Burrell was a young white male that this happened to ... she would’ve made it her business to rectify that situation as soon as it was brought up in the first place," said Leslie Redmond, president of the NAACP of Minneapolis, who wanted Klobuchar to use her influence to press prosecutors to reopen the case.

The current county prosecutor, Mike Freeman, said his office will review new information if it's presented. He also said it's unfair to make the case a “political football” in the presidential race because Klobuchar wasn't the trial attorney on Burrell's trial and was no longer with the office when he was tried, and convicted, a second time.

Redmond said Klobuchar’s track record of not going after police who killed black men set the trend that still exists today.

Excluding fatal car accidents, more than two dozen citizens died during encounters with police when Klobuchar served as Hennepin County’s lead prosecutor. Most of those killed were people of color, according to data compiled by Communities United Against Police Brutality and news articles reviewed by the AP. None of the officers was criminally charged.

“She wouldn’t go after them (police), but then she would go and charge black people for very low offenses. ... Why are we not holding this white woman accountable for her actions? And that is very dangerous, especially when she has used it to advance her political career,” Redmond said.

“This is not about partisanship. Not about politics. This is about justice," she said.

Robinson's podcast, Voting While Black, covers issues well beyond criminal justice. He talked with Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders last fall about “Medicare for All” and discussed voter suppression with Buttigieg, who also has lagged in support from African American voters.

Robinson said he respected the former South Bend, Indiana, mayor for doing the podcast even after he was criticized for his handling of policing in his city and the fatal shooting of a black man by a white officer. Since the taping they've had ongoing conversations on various issues.

That's made Klobuchar's lack of engagement more troubling, he said.

“I worry," he said, "about someone who wants our vote — or maybe she doesn't want our vote — and won't even talk to us.”

___

Burnett reported from Chicago. Associated Press reporters Hannah Fingerhut in Washington and Elana Schor in North Charleston, South Carolina contributed.

___

Catch up on the 2020 election campaign with AP experts on our weekly politics podcast, “Ground Game.”

Yahoo News

Yahoo News