'It's unacceptable to expect DJs to keep going and going': Why Avicii's death is a wake-up call for the music industry

Flying across the world to play to thousands of adoring fans: to the average punter, the life of a globally-renowned DJ seems like a fantasy come true. People have long made fun of touring selectors’ tantrums about the wrong brand of champagne in their rider or a subpar private jet (see: @DJsComplaining).

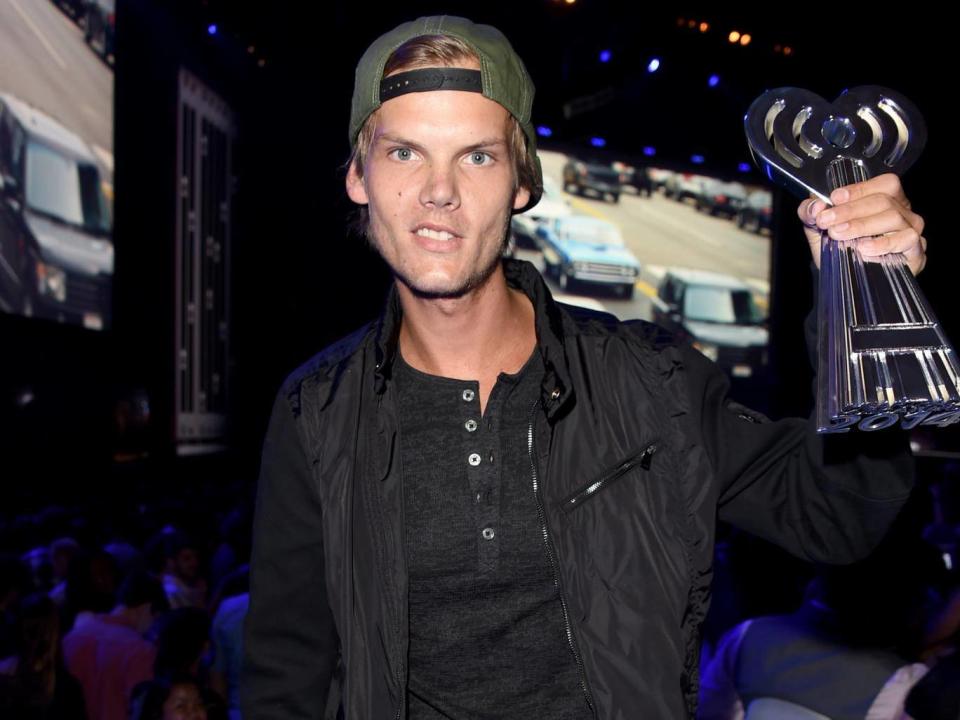

It’s hard, admittedly, to feel sympathy for someone receiving eye-watering sums of money to do a job that looks like one big party. The tragic death of 28-year-old Tim Bergling, aka beloved EDM DJ Avicii, should make us reconsider these stereotypes. Yesterday, the Swedish megastar’s cause of death was not directly confirmed by his family, but they said he could "not go on any longer".

"Our beloved Tim was a seeker, a fragile artistic soul searching for answers to existential questions," they continued. "Tim was not made for the business machine he found himself in; he was a sensitive guy who loved his fans but shunned the spotlight."

Bergling, who toured excessively until quitting completely in 2016, was vocal about the physical and mental health problems induced by his career. A documentary released last year, Avicii: True Stories, showed a man plagued with anxiety and stress, pushed to breaking point by his management and booking agency who repeatedly tried to make him play more shows.

In the film, Bergling is seen saying, “I have told them this: ‘I won’t be able to play any more.’ I have said, like, ‘I’m going to die’. I have said it so many times. And so I don’t want to hear that I should entertain the thought of doing another gig.”

Evidence shows that long touring can take a severe toll on an artist’s physical and mental health. The accompanying lifestyle neglects the basic human needs; disrupted sleeping patterns, physical distance from friends and family, readily available drugs and alcohol and the pressure of performing in front of large crowds can be a lethal combination.

Erick Morillo, Ben Pearce, Benga and B.Traits are just some of the successful DJs who have publicly fought with mental issues caused by life on the road, and it is only in the last few years have they felt comfortable speaking out.

UK charity Help Musicians published a study in 2016, finding that 69 per cent of its 2,211 participants had experienced depression, while 71 per cent had panic attacks and/or high levels of anxiety. People working in music may be up to three times more likely to experience depression than the general public, it found.

It’s a problem that seems to be especially rife within electronic music. Whereas bands usually tour around album cycles, a DJ is often expected to be touring non-stop. Bergling racked up 813 shows in eight years, performing almost 320 times during one of those. The potential loss of money for the artist’s label or management company makes it additionally stressful to turn down new bookings.

Music Support, a charity helping artists suffering from addiction and mental health issues, told The Independent: “There is growing consensus that it is unacceptable to expect artists and DJs to keep going and going and going, often even if they want to. Managers have known this all along, but they need support in looking after their artists from other areas such as record companies, agents and promoters.”

The hyper-speed of the electronic music industry, which can break artists like Avicii almost overnight, increases this pressure to perform day after day. Fierce competition for relevancy makes it hard to turn down a slot. “You have to really stand out now, DJing,” Bergling told GQ in an interview in 2013. “Especially now that [EDM] is getting so big and saturated, and there's a lot more similar DJs competing against each other. People are just coming out of nowhere.”

“A DJ’s career often involves massive highs and massive lows, and learning how to navigate them is an art in itself,” Help Musicians observe.

We tend to focus on the spotlights, CO2 cannons and widespread adulation of the actual set, yet don’t consider the extreme solitude that comes post-performance or after party, with artists stuck in hotel rooms, buses and planes, desperate to catch some sleep. Spending days in transit and dark clubs depletes serotonin through lack of exposure to Vitamin D, while chronic sleep deprivation can cause increased levels of anxiety, a compromised immune system and in extreme cases, a dissociation from reality.

A self-confessed introvert, Bergling was open about struggling with performance anxiety. Discovered at 16 as a bedroom producer, he was thrust into the limelight without much understanding of the industry’s mechanics, and from there his career accelerated at warp speed.

Psychologists have found links between being a professional musician and the personality characteristic of introversion, and many DJs have corroborated this, citing a ‘stage persona’ that is at odds with their real personality. Whereas in the nineties people would dance with each other at concerts, EDM culture is about stadium-sized crowds facing a DJ-popstar expected to act as a frontman; an anxiety-inducing experience for anyone who is used to simply producing in their bedroom.

The mass quantities of alcohol and drugs backstage at these shows can quickly become a crutch for nervous performers. “In the beginning I was too afraid to drink because I didn’t want to screw up,” Bergling, who suffered acute pancreatitis and had his gallbladder and appendix removed, says in True Stories, “but then I realised how stiff I was when I wasn’t drinking. Then I found the magical cure of having a couple of drinks before going on stage. I saw how other DJs drank... DJs who had been in the industry for ten years and they are still drinking at every show.“

British charity Alcohol Concern told The Independent: “When we come to drink more heavily or to rely on alcohol it can lead or contribute to both acute and long-term physical and mental health problems, and damage our lives in other ways.”

Now that we know the risks, how can we make the industry a safer environment for artists? “We believe the solution is in the hands of the music industry itself,” say Help Musicians. In December 2017, the organisation launched the Music Minds Matter mental health service, a freephone number offering routes into counselling, cognitive behavioural therapy and legal and welfare advice.

Artists like Goldie and B.Traits have also advocated practices such as yoga and meditation to maintain a healthy mind, while London nightclub fabric is throwing a guided meditation day next month, donating profits to mental health charity CALM.

At one point in True Stories, Bergling can be seen reflecting on his career, and his words are sobering: “I didn't take the time to really figure out what I wanted to do - I just went along with the flow.“ He adds: “I was running after a happiness that wasn't my own.”

“The music industry is coming to understand the need for a 'gold standard' of touring so we can work together to make sure we are doing everything possible to make sure that burn-out, collapse and, tragically, death stops happening,” says Music Support. “In some instances this will be unavoidable, but there is more that can be done.”

The Music Minds Matter freephone service can be accessed on 0808 802 8008 for advice, information and emotional support, or via musicmindsmatter.org.uk and helpmusicians.org.uk

Music Support’s helpline number is 0800 030 6789, or you can make contact on their website http://www.musicsupport.org/contact

Samaritans can be contacted on 116 123 (in the UK) or via email: jo@samaritans.org

Yahoo News

Yahoo News