'Designer baby' shock sparks WHO call for global genetics research register

An expert panel convened by the World Health Organization has stopped short of calling for a ban on the gene-editing of embryos and instead has said a global registry should be set up to track all research being conducted in the area.

Following a two-day meeting in Geneva, the committee said an "open and transparent" international registry should be set up "immediately" to track all research into human gene-editing.

Although it did not propose a ban on the genetic manipulation of embryos it did say that any such experiments would be "irresponsible".

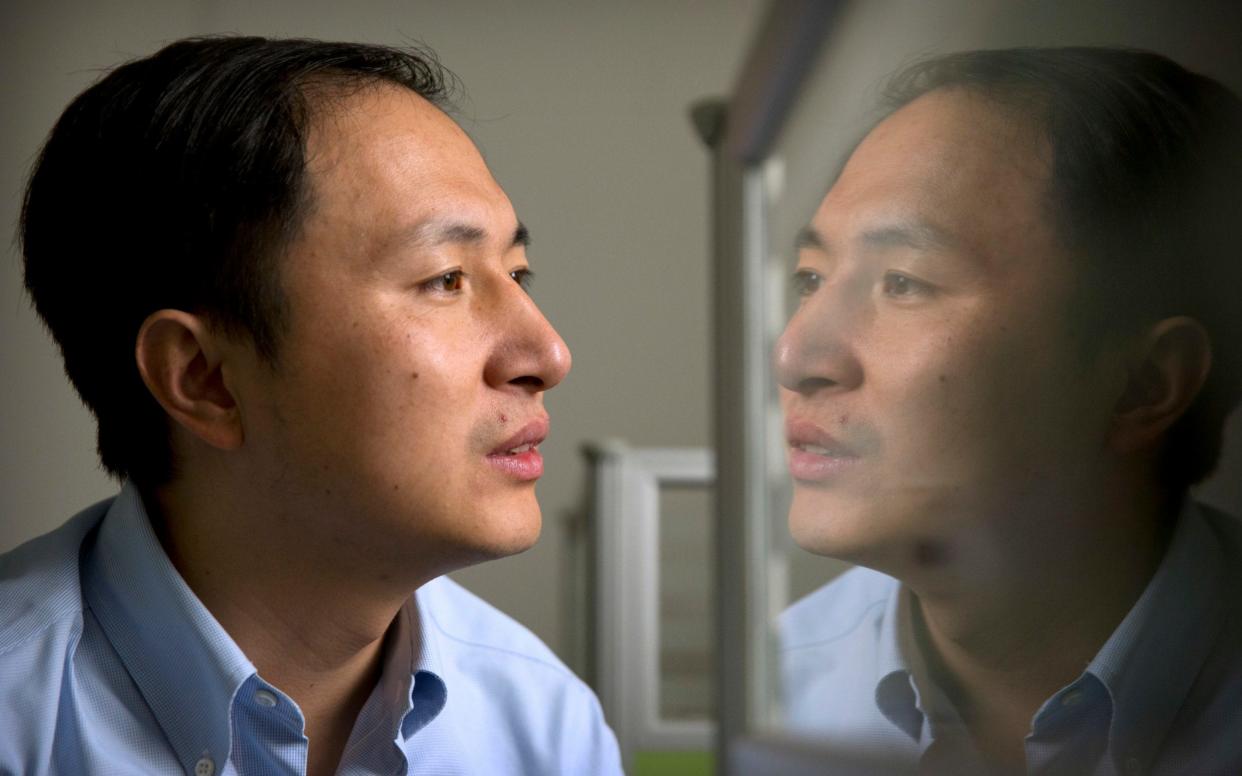

The panel was established in December after the shock announcement that a Chinese scientist, He Jiankui, had edited the embryos of twin girls to give them resistance to HIV. The children, born last autumn, are thought to be the world's first gene-edited babies.

The revelation took the world by surprise and was met with global condemnation. Medical ethics were breached because HIV can be treated without gene-editing and the risks that entails.

Editing the genes of embryonic DNA may also have far reaching consequences as it alters the germline - meaning that the changes made are passed from one generation to another and cannot be undone.

The panel, which included 18 researchers and bioethicists, said there is an “urgent need” to create a transparent global registry which lists all experiments related to human gene-editing, and asked the WHO to set up such a registry immediately.

Dr Margaret Ann Hamburg, co-chair of the WHO panel, said the proposed registry - where scientific journals and funders would have to list anything they publish or finance - would “increase accountability of scientific researchers around the world.”

The database should include studies that edit the DNA of eggs, sperm and early embryos, but should also include those that edit adult cells to curtail disease - which is far less controversial.

The panel added that over the next two years it aims to produce “comprehensive governance framework” for work in the field, to help prevent maverick uses of the developing technology.

But the panel stopped short of proposing a moratorium on germline gene-editing, which was called for by an international group of scientists in an article in Nature journal last week.

"I don't think a vague moratorium is the answer to what needs to be done," said Dr Hamburg. "What we're trying to do is look at the broad picture.

But Dr Hamburg also said: “The committee agrees that it is irresponsible at this time for anyone to proceed with clinical applications of human germline genome editing."

Long-term ethical concern and debate around germline editing revolves around the creation of “designer babies” - embryos modified not just to protect against disease but to produce children with enhanced intelligence, athletic prowess or cosmetic traits.

Stephen Hawking’s final prediction, in an essay published after his death, was that the wealthiest strata of society would soon begin editing their own and their children’s DNA to create a ‘superhuman’ race, with enhanced memory, disease resistance, intelligence and longevity.

He argued this risked dividing humanity into genetic ‘haves’ and ‘have-nots’.

But in an interview in last week's Telegraph George Church, professor of genetics at Harvard Medical School, said the controversy surrounding the editing of human embryos was overblown.

He compared the debate to the short lived moral panic that proceeded the introduction of IVF treatment, predicting that germline editing would eventually be “adopted worldwide”.

“I just don't think that blue eyes and [an extra] 15 IQ points is really a public health threat,” he said, “I don't think it's a threat to our morality.”

He did add, however, that there were legitimate concerns about the technology exacerbating inequalities.

The WHO’s director-general, Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus , welcomed the panel’s proposals. “Gene editing holds incredible promise for health, but it also poses some risks, both ethically and medically,” he said.

Protect yourself and your family by learning more about Global Health Security

Yahoo News

Yahoo News