What's the difference between explorers, anthropologists and tourists?

An anthropologist, an explorer and a tourist walk into a bar. They’re each clutching a spear. The anthropologist describes how it was presented to her on her seventh fieldwork season by the elders of the tribe. The explorer regales them with the tale of how he won the spear upon completing an initiation challenge the tribe had set for him, filmed for a documentary. The tourist explains that he paid $10 for his at the market, and needs to get back now otherwise the cruise ship will leave without him …

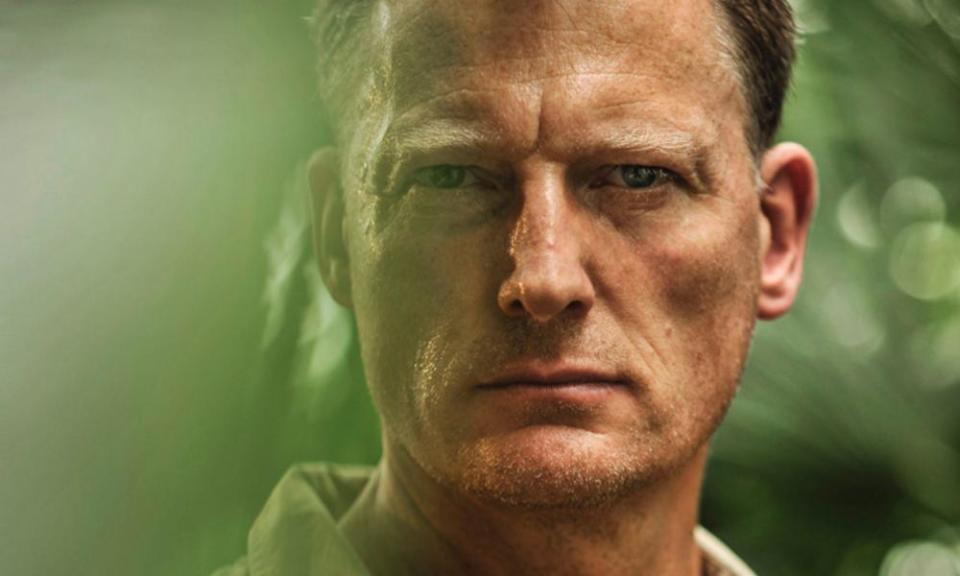

The media attention about the misadventure and recent rescue of British explorer Benedict Allen from Papua New Guinea, and the debate over whether his exploits are culturally appropriate in a post-colonial world, raise a question that’s at the heart of anthropology itself. Why do we travel to other cultures? Who, if anyone, gives permission? Are only some reasons for travel valid? And once you’re there, what understanding do you hope to achieve?

Many of the first practitioners of anthropological enquiry were missionaries and speculators seeking opportunities for travel, trade and religious conversion of colonial “natives”. Theirs was research with a heavy agenda. Fundamental to these early researchers’ understanding was that these races were less civilised by virtue of biology. Carolus Linnaeus, who created the taxonomic system we still use today to describe all species, described four geographical varients of human, Homo, in his Systema Natura in 1758. Europaeus albus, white Europeans, were muscular, sanguine, inventive and governed by laws – their species cousins were between them obstinate, merry, crafty or covetous, and governed variously by custom (Americanus), opinion (Asiaticus) or caprice (Africanus).

In those days, describing the physiology, thought and customs of a tribal native in a distant colony was no more epistemologically problematic than studying the physiology and behaviour of a species of exotic bird. You wouldn’t ask the native for an interpretation of their culture any more than you would ask an animal to explain life in the forest. You – the white European - would observe, describe and explain. You created and curated the truth. A good expedition report was a way to both prove your bravery and your empirical rationality. Derring-do and carefully described specimens – bird, beast and human – would get you ahead when you finally got back to Civilisation.

Racial and cultural theory have moved on, but nonetheless, it provokes the question of how, given shared roots, anthropologists and explorers are different to one another.

Allen described his objective as tracking down a band of people “out-of-contact with our interconnected world”. He insists his work as a professional adventurer-explorer “… isn’t about conquering nature, planting flags or leaving your mark. It’s about the opposite: opening yourself up and allowing the place to leave its mark on you.” That, he explains, is the reason for not taking GPS or satellite phone, which would be standard safety equipment for most remote expeditions. If the locals can’t leave when a dangerous situation or illness occurs, why then, should their white-skinned guest?

One of the principal techniques of ethnographic anthropological field research is participant-observation. The idea is that the anthropologist attempts to live in and become part of the community and culture that he or she is trying to understand. The anthropologist can experience life as an embedded subject, and yet step “out” enough to be able to observe as an objective researcher. Back and forth goes the yo-yo of research – steeped in the complexity of real life, and becoming a more insightful, nuanced observer at the same time. It takes a long time – often years rather than months – to build a body of knowledge. An anthropologist may well have a satellite phone and GPS – but they’re just two additional facts that stand them apart from their hosts, along with their clothes, stature, education, language, skin colour, vaccination programme and regime of anti-malarial tablets (for example). Anthropology acknowledges the problematic nature of the knowledge of others - you can never be fully objective in your observations, perceived as they are through the lens of your personal experience and identity. You’ll never be fully “participant” either – you’ll always be an anthropologist “other”, even if you’re also a member of the community.

For anthropologists in the field, scrutinising personal responses to experiences is part of being a good, reflexive researcher. But for most, the personal remains peripheral. The central focus is the group of people you’re studying.

And yet anthropologists in the field may well want to make a name for themselves, are expected to show the impact of their research back “home” and seek to raise awareness and understanding of the people they’re studying. Self-interested motives can easily lie alongside the desire to help an indigenous community. Plenty of communities might not benefit at all from an anthropologist’s academic output.

Explorers tend to be upfront and unapologetic about their quest for adventure. They seek remote and difficult destinations to test and learn about themselves as much as the people they meet. Rainforest and mountain become proving ground and playground, as well as a way to tell a story about a place and people the rest of us might not otherwise know about.

And what of the non-professional? Can tourists visit remote places and seldom-contacted people ethically? Or is is always degrading and exploitative to the indigenous people? In some places I’ve travelled, it feels like tribal tourism exploits the tourists seeking an “authentic” cultural experience more than it exploits the entrepreneurial locals offering dance performances, traditional costume, or market knick-knacks.

It’s perhaps as patriarchal – with all the echoes of colonial-era racism – to suggest that it’s for “us” to decide what is or isn’t ok for “them”. Maybe the remote Papua New Guinean tribe want to welcome the ageing white guy who last showed up thirty years ago. Maybe once-remote peoples see holidaying visitors as a key revenue stream for their 21st-century lives. And maybe the adventurous anthropologist with tenure in mind is no more or less self-interested than the tourist who wants an exotic selfie for instagram, or the explorer who wants another yarn to tell.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News