'Heroin is very good at getting rid of all my problems': drugs and sexism in India

After selling heroin on the streets all morning, former school teacher Jenny is tired and in need of her next hit. Carrying her earnings, she travels to a decrepit house on the outskirts of Imphal, capital of the north-eastern Indian state of Manipur, to find some relief.

It’s here that drug users openly inject and unwind, and where Jenny, 46, picks up her next gram of heroin to sell on the streets. She can’t remember when she began injecting heroin – she thinks it was about 10 years ago when problems with her husband reached boiling point – nor can she remember the last time she saw her two children.

“Heroin is very good at getting rid of all my problems. If I don’t get it, it’s very hard,” says Jenny, while describing how she lives on the streets, sometimes sleeping in public toilets or the nearby forest, other times at hotels where she does sex work. “I need treatment. I will quit, just tell me where to go.”

In 2011 India was hailed for its introduction of methadone maintenance treatment (MMT) to reduce drug dependence and HIV and hepatitis C infections among users. Methadone works by blocking the “high” caused by using opiates and helps reduce cravings and withdrawal symptoms.

But six years on, despite strong evidence of its benefits, the criminalisation of drug use, inadequate services and an emphasis on detoxification and rehabilitation remain major barriers to the ability of drug users to access treatment.

ForJenny, simply being female makes it even harder. She faces the double stigma of being a drug user and a woman, which immensely hinders the ability of people like her to overcome addiction.

A fear of judgement and discrimination, of being shouted at or abused, means that many female drug users in India often delay or completely avoid seeking treatment.

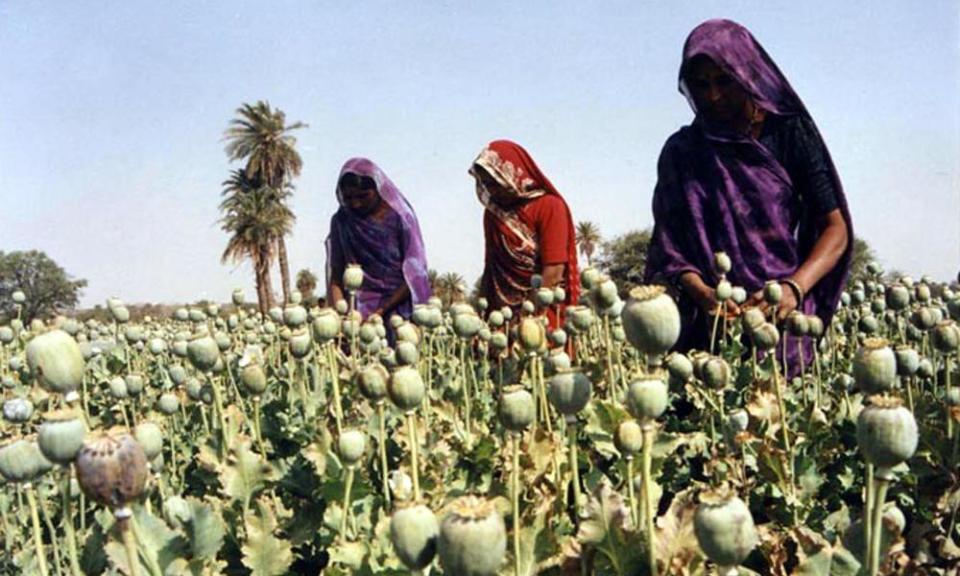

The result is that far fewer get treatment. In Manipur where Jenny lives, for example grug use, HIV and hepatitis C are all rife, fuelled by the state’s porous border with Myanmar, one of the world’s largest producers of heroin. The area has the highest percentage (28.2%) of female drug users [pdf] out of seven states in north-eastern India, and half sell drugs or sex to pay for their addiction. However, only 5% of users enrolled in the MMT programme at the Regional Institute of Medical Sciences in Imphal, are women, says regional coordinator Thokchom Indira Devi.

Devi’s research assistant Loli adds that female drug users face structural and institutional barriers to accessing services. “When you look at the set-up it’s very difficult for women to come here. The services are male-centric so even though women are welcome here, they ask: what will people think? What will the community think?”

One of the major barriers preventing women from accessing treatment is that in order for patients to be eligible for government-run MMT programmes, these have to be their last resort. In other words, the drug user has to prove they have tried rehabilitation or detoxification and failed. But the vast majority of drug rehabs and detox programs in Manipur only accept men, and among the few that accept women cost is a major barrier. In fact, a 2012 study on Manipur found a “desperate need for women-only and women-friendly drug and alcohol detoxification and rehabilitation centres that are low-cost and can accommodate children.”

Women more likely to share needles

Across town at a drop-in-centre run by the Nirvana Foundation – one of the few organisations in Manipur that specifically supports female drug users – women rest, shower, pick up condoms and receive medical check-ups. The foundation’s general secretary Sobhana Sorokhaibam explains how the women they see are more prone to HIV and other blood-borne viruses because they are more likely to share needles. She puts this down to them being less able to access clean needle-exchange programmes and having unprotected sex because of their lack of negotiating power.

Women are more likely to share needles than men, she says, because they are only able to access one clean needle per day at government-run programmes despite research showing women inject more frequently than men.

They could purchase more but it comes at a cost. Jenny says it’s a trade off between either sharing needles or having sex with more clients so they can afford to purchase new needles at the pharmacy.

On the top floor of the centre, a dozen women, many with bloodshot, glassy eyes and bruises down their arms, lie on the floor.

Most have never tried to get clean, not because they don’t want to, they tell us, but because of stigma. They say they are trapped in a vicious cycle of drug use, sex work and homelessness – all issues that fuel stigma about their situation.

“We are all struggling,” says Susmina, 29, who is homeless and has been injecting heroin for two years. “We were chased out by our families. We need a shelter, a safe place to go.”

Gender bias in healthcare gets worse as cost of care rises

That women struggle more than men do to access treatment for drug use in India is not entirely surprising: gender plays an important role in all health outcomes for women in the country.

Gender roles and norms have significant influence over how women and men access health services and how the health system responds to their different needs. Research shows [pdf] that from birth and right through their life, females in India are less favoured than males, which often translates into poorer health outcomes.

A girl in India is more likely to be killed at birth and more likely to be under-nourished; she is also less likely to access healthcare or to be taken to a hospital compared with men, and is more prone to stigma relating to mental illness and drug addiction.

Shamika Ravi, senior fellow at the Brookings Institute India, recently completed a study of gender bias at India’s largest public healthcare provider, the All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIMS), across five states.

“Gender bias gets worse as cost of care rises,” she says of the study’s results, which are yet to be published. “Women are seldom brought to the hospital because the perceived benefits of providing care is not seen. There’s a gross neglect of girl’s’ health over their lifecycle. We need a strategy to tackle gender bias but so far efforts have been fragmented.”

While there are schemes that provide incentives for women to give birth at hospitals and immunise their daughters, along with retaining girls at school, no schemes specifically address the root causes of gender inequality and structural sexism.

Back at the run-down house in Manipur, Jenny has injected twice. She hangs her head low, murmuring incoherently.

Another drug user hits her to wake her up, telling her to get back to work. On the bus into town she asks: “How long am I going to stay like this for?” No one answers and still high, she falls back to sleep.

Some names have been changed.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News