'A killer is always a killer’: Gambia gripped by Junglers’ testimony

One of the most notorious killers in Gambia sits on a grubby mattress on his brother’s stoop, uneasy in his newfound freedom. His nephews fetch cigarettes and brew tea, and birds sing in the mango trees. A cuddly toy crocodile lies near the gate.

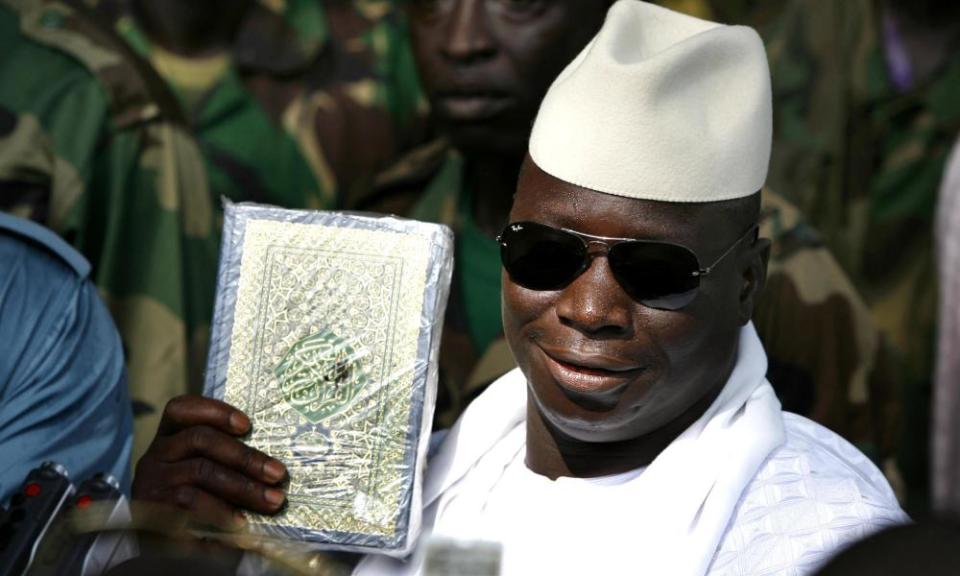

Malick Jatta was a member of the Junglers, a death squad trained to do the dirtiest work of the country’s former president, Yahya Jammeh, whose abuses over 22 years in power are being revealed by a truth, reconciliation and reparations commission broadcast live into the living rooms of Africa’s smallest mainland nation.

The appearance of Jatta and five of his fellow Junglers over the past three weeks has been the most gripping episode yet of this reality TV of the most sinister kind.

Sitting in his uniform and beret before a panel of commissioners, Jatta, the first Jungler to testify, explained how he and his team shot dead one of Gambia’s most prominent journalists, Deyda Hydara.

The second, Omar Jallow, described in gruesome detail how he led west African migrants wrongly accused of being mercenaries to their death, one by one, before Jatta and another Jungler executed them, their bodies falling into a ditch. Jatta admitted to killing only one migrant.

Some of their victims were suffocated with plastic bags, some they shot, others they cut into pieces or threw into wells. Their reward for this testimony was to be released, to the outrage of many Gambians, especially their victims’ families.

“A killer is always a killer,” said Aisha Jammeh, who was in the front row at the TRRC when Omar Jallow described how he tied a rope around the neck of her father, a cousin of the former president with whom he had fallen out, and helped strangle him to death.

“It’s unacceptable that these people go freely in the streets,” said Baba Hydara, son of the murdered journalist. “They’re not remorseful. They’re only trying to save themselves from spending the rest of their years in jail. They’re not even truthful.”

Jatta went back to the coastal village where he was born, Tujereng, whose inhabitants are said to be protected by spiritual forces. He was home in time for the Eid celebrations.

By turns contrite, defensive and paranoid about his personal safety, Jatta told the Guardian that he would be on his knees to his victims’ families if they would let him “boldly ask for their forgiveness”, but also blamed the killings on Jammeh, the chain of command in the army – and God.

“He (God) ordained it. He may have a purpose that you and I will not know,” Jatta said, rolling a cigarette. “Whatever we do is only from His decrees. I’m not a bad person.”

Jatta’s return is the talk of Tujereng. Every household is hooked on the TRRC, and particularly the testimony of a homegrown Jungler.

“The military changes people,” said Seedy Jammeh, who struggles to reconcile the mild, well-liked boy he had known with the killer describing his gruesome murders on TV. Jatta never harmed anyone in Tujereng, he said, though people were frightened by the arsenal of guns and grenades in his car.

“People are less afraid now that Malick’s spoken at the TRRC,” said Landing Jatta, another childhood friend. “They understand that what he was doing was not his will.”

Letting the Junglers go was the lawful thing to do, the justice minister, Abubacarr Tambadou, told the Guardian, as none of them were charged with any crime in more than two years of detention, while other self-confessed perpetrators walked freely.

“We want to ensure that we dispense justice fairly and equitably,” he said.

Tambadou has only let four go so far and will decide in the next few days on the fate of the other two– who repeatedly lied to the TRRC, according to its lead counsel.

The executive secretary of the TRRC, Baba Galleh Jallow, said the Junglers could still be prosecuted. “There’s no guarantee of amnesty. There’s no guarantee of anything,” he said.

Tambadou hoped it would encourage the Junglers who had fled the country to come home and testify. Eventually, this could provide the basis for prosecuting Jammeh himself, though the minister said the country was not yet ready for that.

“The fingers are pointing in one direction, but we’re in the truth-telling phase,” he said. “We’ll cross that bridge when we come to it.”

However, some of the Junglers’ victims said the government was making a big mess that they would live to regret. “He cannot guarantee anything. It could all fall apart,” Hydara said.

Slouching on his mattress, Jatta said he owed it to the Gambian people to testify against Jammeh in any future trial even if it meant the ex-president, whose former henchmen still occupy some of the highest positions in the country’s security forces, would try to have him killed.

“Be me alive or dead, Gambia will remain,” he said. “My nation is more important than Jammeh. Why would I step back? I have no fear. All I fear is the man I have offended. But not he who put me into mess.”

Hydara said he suspected the country’s politically isolated president, who is widely thought to be trying to attract support from Jammeh’s former party, had wanted the Junglers to be released knowing that it would please these potential voters.

“I think we’re getting ahead of ourselves here,” said Tambadou when asked about this. “I have no reason to doubt the commitment of the government or the president in seeing out the recommendations of the TRRC when they are made.”

Releasing the Junglers may have been controversial, but it has not made the TRRC any less popular.

During the day, security guards listen live on radios and cafes play the broadcasts in lieu of music. Villagers gather in their chiefs’ parlours to tune in together. Those with day jobs watch replays in their bedrooms at night. Gambians living in the diaspora follow it religiously, and some drop by the commission hall in their summer holidays to see the proceedings in person.

“It was a hit in the nation,” said Aisha Jammeh, who has been struggling to sleep since hearing the story of her father’s death. She did not mean that as a compliment. It was “using our stories” to earn Gambia undue credit at home and abroad, she thought, and detracting from what victims really wanted: for perpetrators to be brought to justice.

“They could have charged them (the Junglers) when they arrested them two years ago, but they did not charge them – they were just waiting for the show that is the TRRC.”

As for forgiveness for her father’s killers, she said: “It can’t be that simple. It must be as hard as finding a diamond. Too much is being asked of me. Just forget it and move on? It doesn’t work like that.”

Additional reporting by Mafuji Ceesay

Yahoo News

Yahoo News