'No regrets': world's biggest election loser runs for 96th time in Canada

The first time John Turmel ran in an election, it was 1979 and his primary aim was to legalise gambling. While his door-knocking efforts earned him just 193 votes, the race marked the start of an obsession that would eventually launch the Canadian into the record books for having contested, and lost, the highest number of elections in the world.

Some four decades on, Turmel has contested 95 elections, throwing his hat into the ring for jobs ranging from city councillor to MP. Often running as an independent, the number of votes he receives fluctuates wildly, from 11 to 4,500.

Long-winded and prone to campaign ideas that fly in the face of science – such as describing climate change as a hoax – the perennial fringe candidate has racked up a string of bruising headlines over the years. “Super loser fails again,” read one article, while a recent radio appearance dubbed him “politics’ biggest loser”.

Turmel is quick to wave off the criticism. “Am I feeling bad? No,” says the 67-year-old in an interview in his cluttered home office in Brantford, a small city of some 99,000 in southern Ontario.

To the self-described professional gambler elections are not there to be won or lost, but rather a low-cost means of disseminating ideas.

Turmel’s first foray into elections was prompted by a police crackdown on the underground blackjack games he was running in Ottawa. “I kept getting busted,” he says. “So I ran for parliament in 1979 to legalise gambling and stop busting me.”

His platform soon expanded to legalising drugs and prostitution as well. “I was called the champion of the gamblers, hookers and dope smokers.”

That campaign – taking place in a year in which inflation rates averaged around 9% – left Turmel fending off a constant stream of questions about the economy. By the time the election rolled around, he had added the idea of abolishing the interest rate to his program.

The idea blossomed into a fascination with what Turmel calls “a gentle kind of capitalism,” referring to interest-free barter arrangements such as “time banks”.

These arrangements offer people the chance to create an alternative currency, backed by their own goods and services, explains Turmel. “People with no money can basically create their own tokens by monetising their own time.”

Convinced that this was an idea whose time had come in Canada, he seized on the elections as a way to spread the word. “So that’s why I kept running,” he says.

“I realised that I’m going to have to take advantage of every opportunity to explain how we could save ourselves from poverty, which is created by not enough money. We’ve got lots of wealth, lots of food, lots of clothes, we’ve just got not enough money to buy it.”

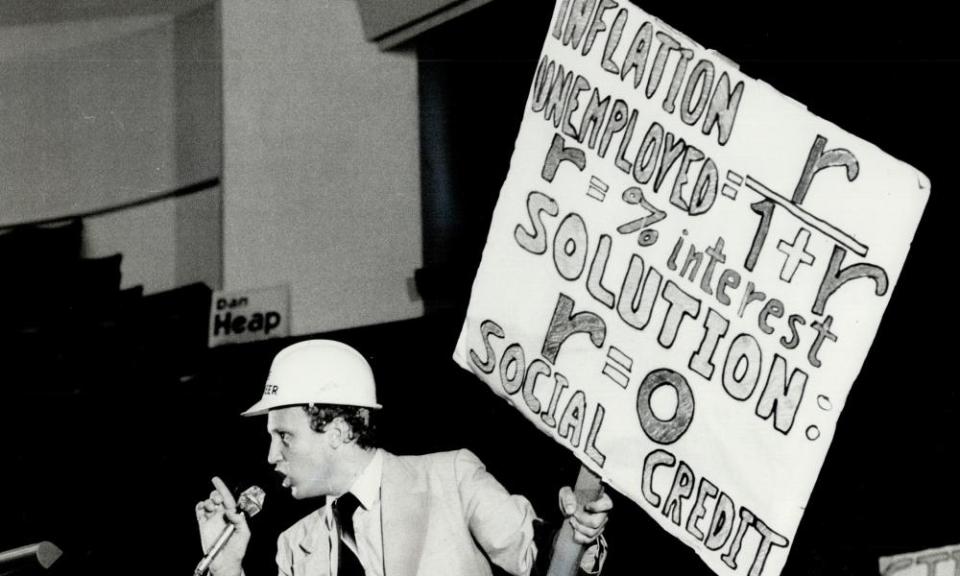

Clad often in his lucky playing card tie and a white construction helmet emblazoned with the words “Turmel the Engineer” – a reference to his bachelor degree in electrical engineering – he has become a polarising fixture in Canadian elections, referring to himself as the “smartest man on Earth” while describing the masses as “slows”.

In recent years he has eschewed going door-to-door for a far more confrontational style of campaigning; showing up at all debates – including those he hasn’t been invited to – and regularly being escorted out by police.

“I do zero campaigns,” he says. “I go and I sign up, I give them a press release and a press conference and then I’ll go home. And if there’s a debate, I’ll show up.”

At times though his unconventional strategy has paid off; one month after an Ontario newspaper described him as a “super loser”, a second article detailed the creation of a group committed to launching a local currency.

“Mission accomplished,” says Turmel, a note of pride creeping into his voice as he holds up the two articles.

The little that he does end up spending comes from his gambling winnings. “I live three blocks from the biggest poker game in the country which has allowed me to finance all my activities,” he says. Two years ago he started receiving a pension, which now supplants the income he says he once earned from poker.

While he has stopped playing poker for the most part, he shows little sign of slowing down when it comes to elections – Turmel is currently running in his 96th election campaign, this time for mayor of Brantford, the city where he lives.

Looking back on four decades littered with electoral losses, he turns combative when asked whether it has all been worth it.

“Who cares? I’m doing my duty. I just show up, do my best – which is my duty – sit back and see what happens.”

His voice calms as he adds: “I have no regrets. For a guy with no resources, doing it all with my winnings from mainly illegal games, what have I got to be ashamed of?”

Yahoo News

Yahoo News