'What do we do now?': the New Labour landslide, 20 years on

They all remember the sunshine. Talk to those who were there on 1 May 1997, and everyone mentions the way the whole country seemed to glow under bright blue skies and a warm sun. It had been that way for much of the campaign, but those at the centre had barely had a chance to enjoy it. Now, on polling day, time at last seemed to slow down. For those few hours, there was nothing more that the small, tight group at the heart of New Labour could do, except wait.

Thanks to Theresa May’s decision to call an early election, the campaign of 2017 will encompass a poignant milestone: the 20th anniversary of the biggest landslide in British political history. On Monday, two decades will have passed since Tony Blair led Labour to a triumph so complete it eclipsed even the groundbreaking win of 1945. While Clement Attlee racked up a Commons majority of 145 seats, Blair managed 179. Nothing like it had been accomplished before – or since.

When you’d lost as many elections as we had, you believed right until the end that some unforeseen event could derail us

Drawing on conversations with the key players who propelled Blair and Gordon Brown into power – Alastair Campbell, Peter Mandelson, Ed Balls, David Miliband, Anji Hunter, Jonathan Powell and others – it’s possible to glimpse again that extraordinary day when Britain turned its back on 18 years of Conservative rule and stepped into an unknown future, led by a group of people who, as one puts it now, had “no idea what the inside of government even looked like”. They tell stories of jubilation and mild panic as the results came in – and of landmark achievements and enduring regrets, as that victory turned into a 13-year spell in government.

On the day itself, no one was allowed to celebrate, not until all the votes were counted. For Blair, it was part superstition (don’t jinx it by taking it for granted), part bitter experience. “When you’d lost as many elections as we had by 1997, you believed right until the end that some unforeseen event could derail us,” says Mandelson, then MP for Hartlepool and campaign director.

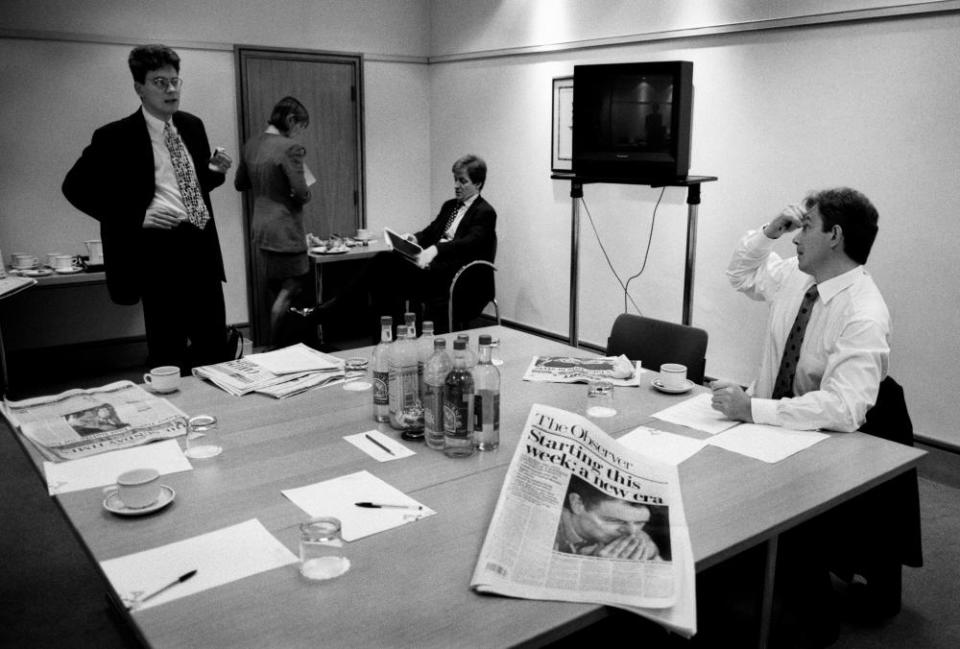

Blair had been in that frame of mind throughout. When he saw the front page of the Observer on the Sunday before polling day – with its headline, above a portrait of himself, “Starting this week: a new era” – he was “appalled”, remembers Hunter, who until 2001 served as the leader’s gatekeeper and unofficial voice of middle England. Blair had refused to say or do anything that smacked of presumption or complacency, even when every poll showed he was on course for Downing Street.

On 1 May, he allowed himself a small exemption: since there was no more campaigning to be done, he agreed to discuss tentative plans for the Labour government that might – all conversations had to be framed in the conditional – begin the next day. At Myrobella, the former pit manager’s house he had in his Sedgefield constituency, he took his first peek at the document chief of staff Jonathan Powell had drafted, outlining a plan for Labour’s first 100 days in office. Until then, Powell says, “He hadn’t wanted to look.”

Blair alternated between pacing inside the house and sitting in the garden. “He was apprehensive,” Powell recalls. “He’d call Sally [Morgan, a senior political aide] and say, ‘What’s going on?’ She’d make stuff up: ‘Oh, turnout’s good in the East Midlands.’ It was complete nonsense. Anything to get him to shut up.”

Mandelson, Campbell, Powell and Hunter were all there. John Prescott came over from Hull, before heading back to his own count. In the garden, “We permitted ourselves a theoretical discussion of who might fill various posts,” Mandelson remembers. But mainly they remained in the same curious state of limbo, halfway between opposition and government. “There was a sense that everything was happening in slow motion,” he says.

“I was completely exhausted,” recalls Campbell, then Blair’s spokesman and right-hand man. The campaign had been relentless and Campbell had been fierce about maintaining discipline, including over his own emotions. But the night before, he had been on the phone with his 10-year-old son, Callum, who asked, “Are we going to win?” That “we” was too much. “I put the phone down and I started crying. I cried for about half an hour.”

Meanwhile, on the streets of Enfield Southgate, David Miliband, then Blair’s head of policy, was canvassing with Stephen Twigg, a former student leader whose hopeless task was to take on the Conservative cabinet minister Michael Portillo. They’d been leafleting big houses: obviously solid Tory ground. Eating lunch at a pub, Twigg laughingly revealed that Millbank, Labour HQ in those days, had sent him a draft victory speech. “No chance of that happening,” he said, unaware that a matter of hours later his sheepish grin, alongside a shell-shocked Portillo, would become one of the defining images of the election.

Eventually, evening came. A BBC contact had leaked to Hunter the details of the exit poll. But Blair shooed her away. “He didn’t want to hear it.”

At 10pm, David Dimbleby forecast an enormous Labour win. The early results confirmed it. But still the inner circle was counting no chickens. At one point, hearing that champagne corks were popping at Millbank, Campbell got on the phone to give the London team a carpeting. Not the right look for the cameras, he barked. Press officer David Hill told him, “We are about to win the biggest victory in our history and end 18 consecutive years of Tory government. I think it’s going to be a little hard to tell them all to look sombre.”

My pager kept going off: Labour gain, Labour gain, Labour gain, Labour hold, Labour gain, Labour gain…

Blair once told me of the moment Bruce Grocott, his parliamentary private secretary, came to him and said, “I’ve got good news and bad news. The good news is, you’ve won by a landslide. The bad news is, landslides happen.” Even the prospect of massive victory was tainted by the familiar Labour angst: they might be voting you in, but they could just as easily throw you out.

Soon, John Major rang, conceding defeat. Blair took the call in the house’s small study; Campbell and Powell huddled around, trying to listen in. Campbell remembers that Blair was “wearing a rugby shirt, shorts and these ridiculous fluffy slippers. It didn’t feel like a historic moment.”

It was time to head to Blair’s count. His son, Nicky, couldn’t be woken and had to be carried to the car; this team of political sorcerers were still young. Campbell, who had intimidated the entire Westminster press corps, was 39; Blair was not yet 44. As he went into the sports centre where the Sedgefield votes were being tallied, Campbell gave a TV interview, again stressing that nothing could be taken for granted. His demeanour was downbeat. His pager, state-of-the-art technology at the time, started buzzing as colleagues asked the same question: “What is wrong with you?”

Mandelson flew to London alongside novelist Robert Harris, granted access for an insider’s account. “As we flew down, we listened to the radio – we must have been flying low – as one after another of these southern coastal seats began falling like dominoes.” Campbell was on another flight, with Tony and Cherie Blair. “My pager kept going off: Labour gain, Labour gain, Labour gain, Labour hold, Labour gain, Labour gain…”

Meanwhile, Ed Balls, then right-hand man to Brown, was dozing in the back of a car as he was driven to London from Castleford where his wife, Yvette Cooper, had just been elected as MP for the first time. At one point, Balls woke with a start: the driver, a trade union volunteer, had let out a roar on hearing the news of Portillo’s defeat.

I refuse to list Iraq as an upfront regret, because I don’t believe it

Once in London, the Blair team headed towards the victory party at the Royal Festival Hall. They arrived to a crowd of activists, MPs, trade unionists, celebrities and party workers in a state of near ecstasy. I remember it well: I was there, notebook in hand, watching as Richard Branson mingled with John Edmonds of the GMB, and as a delighted, relieved Neil Kinnock danced with Peter Mandelson. As the sun came up, Blair ad-libbed that line with its oddly Majoresque cadence: “A new dawn has broken, has it not?”

But the euphoria of the crowd, felt across much of the country on that Friday morning, did not fully extend to those on the inside. “I was scared,” Blair wrote in his memoirs. Hunter thinks “the weight, the awesome responsibility” pressed in on him. What was going through her mind? “Tony needs to have a sleep, that’s what I was thinking.”

The Blairs went back to their Islington home to get a few hours rest – a drowsy Cherie famously snapped by a waiting press pack as she opened her front door - but the others either got much less sleep or none at all. Powell went to Downing Street, charged with performing in a few hours a transition from one administration to another that in the US takes three months. Mandelson went to Millbank, partly to mug up on a parliamentary Labour party now boosted to 418, including scores of new MPs “who we’d frankly not heard of and knew nothing about”. Brown and Balls headed for the Treasury, where they handed stunned civil servants a letter announcing their intention to make the Bank of England independent. Immediately.

At around 6am, David Miliband and his wife, Louise, walked across Waterloo Bridge, stopping to watch the morning sun glinting on Big Ben. “I guess I thought, ‘What do we do now?’” he recalls.

***

I asked these key players in New Labour to name three things they were proudest of in the years after the great landslide, and three regrets. The positives were easy, though not entirely what I predicted.

Naturally, Powell offered the Good Friday agreement, in which he was intimately involved, while Campbell cited the military intervention in Kosovo. (Campbell was sent to get a grip on the communications effort for Nato during that war in 1999, and has retained his interest: he’s lost count of the young adults he has met in Albania called Tony Blair, named for the man their parents believe saved their lives.) Balls was proud of the decision to keep Britain out of the euro, as well as the post-2001 rise in national insurance to fund the NHS, a tax rise levied explicitly to pay for a public service: “No left-of-centre government had done that.”

Others ticked off signature New Labour achievements, the kind that used to be listed on giant TV screens as the warm-up video for the leader’s speech at party conference: increased investment in schools and hospitals; devolution to Scotland, Wales and London; the minimum wage; civil partnerships; sharp reductions in poverty among pensioners and children; a massive redistribution of wealth to the worse off through the creation of the tax credit system.

Miliband said he was proud that the 1997 government created the Department for International Development, while speechwriter and strategist Peter Hyman says he still admires the fact that Blair “never pandered on immigration”, and that, in those years, the country felt, broadly, tolerant, inclusive and optimistic: “It was the best time to be British.” All of them cite Labour’s three consecutive election wins, a sustained success that, again, outstrips Attlee’s. “The 1945 government was a shooting star: it had lost all of its energy by 1950,” Miliband says.

Twenty years on, the regrets are harder to talk about. Balls is critical of himself and his colleagues over the “searing event” of the 2008 financial crash. Like their fellow governments around the world, he says, Labour failed to see the “building problem” in the financial institutions until it was too late.

Nothing is more damning than the fact that, 20 years on, Jeremy Corbyn is leader and Labour is about to be annihilated

Others speak of the 2003 invasion of Iraq that devoured Blair’s second term and destroyed his premiership – though not without prompting. Defiantly, Powell says that, in terms of its impact on Britain, “Iraq will be forgotten in five or 10 years.” Likewise, Campbell says, “I refuse to list that as an upfront regret, because I don’t believe it.”

Thanks to Brexit, self-criticism comes more easily over Europe. “We didn’t talk Europe up enough,” Hunter says. “Everybody slightly pandered to the Daily Mail agenda on Europe – ‘the gravy train’ and all that. We didn’t fight that.” Miliband puts it succinctly: “We won arguments in Europe, but didn’t win the argument for Europe.”

Most of the class of 1997 reject the idea that it was their actions that stored up so much of the current trouble, starting with the suggestion that it was the arrival of 1.5m eastern European immigrants after 2004 that ultimately led to last year’s Brexit vote. No, they say: while it would obviously have been better to have managed that influx more gradually, it did not lead ineluctably to Brexit. The case for migration could have been made more effectively; David Cameron could have got a better deal from his renegotiation with Brussels. (Blair would have, Hyman says.) Balls is more unforgiving: “We thought globalisation would be all about the movement of goods and services; we didn’t anticipate that it would mean the mass movement of people.”

Only in one area are the founders of New Labour ready to see a direct line of responsibility and blame, and that is in the area that wounds them most deeply: the current plight of the Labour party, a few weeks out from what promises to be a very different general election.

“We have to take some responsibility for the state Labour is in today,” Campbell says. “We can’t say Corbyn happened in a vacuum. We didn’t cement the legacy.” Hyman goes further: “Nothing is more damning than the fact that, 20 years later, Jeremy Corbyn is leading the party and Labour is about to be annihilated.”

There have always been parts of the Labour party that find the discipline of government, of compromise, hard

The architects of New Labour watched as their record was first questioned and then rubbished. For that, many of the 1997 veterans blame Ed Miliband, about whom they can be scathing – and not just for making the rule change that meant party members alone, including ones who’d just signed up, could now elect the party leader, with no extra weight given to the views of MPs. They say that, by declaring New Labour “dead”, Miliband prepared the ground for Corbyn.

And so now Labour is led by a man who either never speaks of the last Labour government or, if he does, seems to regard it as an embarrassment requiring atonement. While the Tories exult in their victories, lionising their winners and boasting of their time in office, Blair is mainly cast as a source of shame. For his part, as if to confirm how much the political landscape has changed since 1997, Blair now suggests that people vote in June for the most anti-Brexit candidate – even if that means voting Tory.

Part of New Labour’s failure was one of personnel. Most agree that they failed to bring on a new generation, that fresh talent struggled to grow in the shade cast by Blair and Brown. But it goes deeper than that. Balls thinks New Labour was, in part, a victim of its own success. “There have always been parts of the Labour party that find the discipline of government, of compromise, hard. I think the party was quite exhausted by government. But, to be fair to Ed Miliband, that discipline held for another five years.” When 2015 brought a second election defeat, Balls says, “People said, ‘Oh God, can’t we just get back to dreaming? Can’t we be outsiders?’ So, in some ways, the success of Blair and Brown, being in power that long, caused a pent-up resentment about all the discipline and compromise.” After a long, hard hike on the road to power, electing Corbyn felt like sinking into a warm bath.

Some of the New Labour team wonder how things might have been had their bosses, Blair and Brown, been able to repeat in government the effective working relationship they had during the 1997 campaign, instead of allowing the tension between them to gnaw at New Labour from the inside. Powell’s big regret is that nothing came of the “project” of convergence – maybe even merger – with the Lib Dems.

As for the future, no one – not even the truest believer – suggests a simple resurrection of New Labour. They know that the world of late 1990s Britain has gone and is never coming back. But it’s worth remembering all the same. David Miliband says that if the party keeps disdaining its 13 years in power, if “we forget why it’s worth having a Labour government, we end up not having one”.

New Labour’s mistakes and misdeeds were legion – and, whatever Campbell and Powell say, Iraq surely belongs at the top of that list. Still, its key insight – that Labour could do radical things, but only once it had reassured the electorate it was fit to hold power – holds as true now as it did in 1997.

The founders of New Labour look back with pride at the victory they won two decades ago, but the memory is bittersweet. For they know the prize eventually slipped out of reach – as bright and brief as a glorious May afternoon.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News