An alleged sexual predator, Republican civil war and Steve Bannon: what's at stake in Alabama?

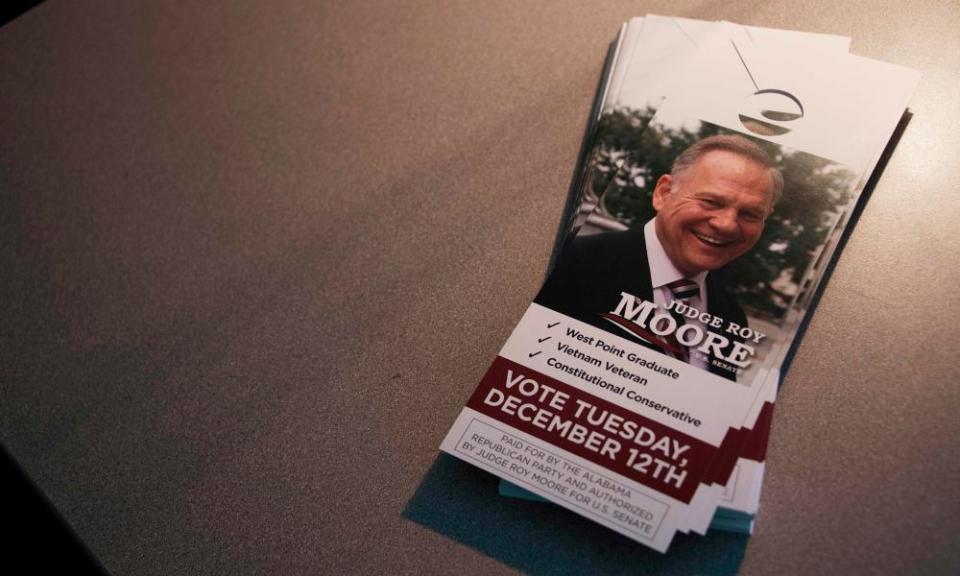

On Tuesday, Alabamans will go to the polls to decide which is the lesser evil, an accused child molester or a Democrat. In recent polls, the accused child molester is favored.

The surprise is that a Democrat even has a chance in a deep red state that Donald Trump won by a landslide in the 2016 presidential race. The concept that a Republican might be vulnerable is almost as unusual as the white-flecked fields of rural Alabama in December, where snow mixed with leftover cotton bolls to produce an Arctic landscape in the Bible Belt.

But Roy Moore is not a normal Republican and 2017 is not a normal year.

On 9 November, the Washington Post published a story that alleged Moore had sexually assaulted one teenage girl and romantically pursued three others when he was in his 30s. In the following days, another accuser came forward to say Moore had sexually assaulted her as a teen. Other women claimed Moore pursued them – one even said Moore summoned her from a high school trigonometry class to ask her on a date.

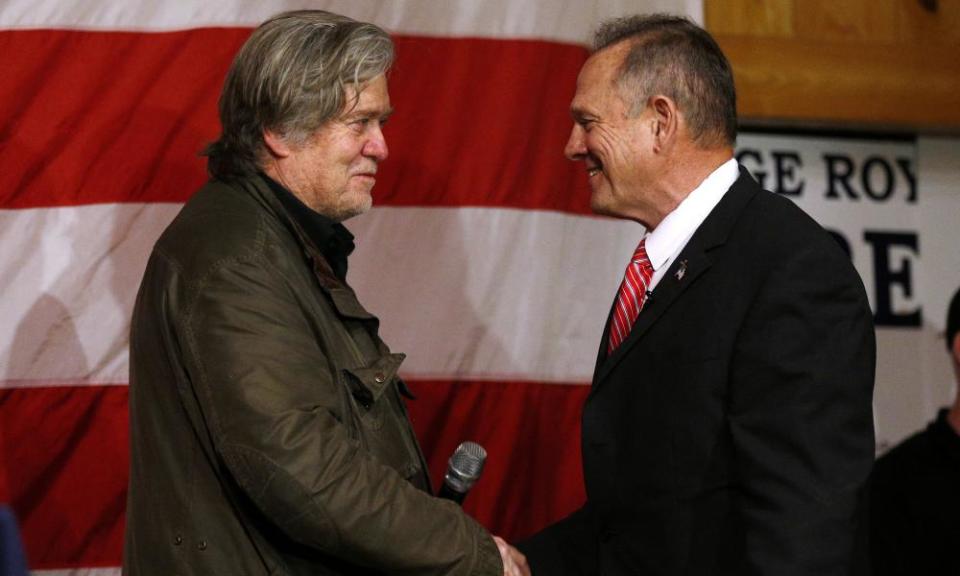

National Republicans fled from Moore and urged him to drop out. The only prominent figure to stand by him was former White House strategist Steve Bannon. Moore became a figure of ridicule, mocked by late-night TV hosts and Saturday Night Live.

It turned the race into the political version of the standoff in The Good, the Bad and the Ugly: a three-way fight between Democrats, establishment Republicans and the Trump wing of the Republican party.

Democrats saw an opportunity to pick off a seat and shrink an already slender Republican majority in the Senate, impeding efforts to pass Trump-agenda cornerstones like tax reform. Washington Republicans saw an impossible choice between a far-right firebrand and a Democrat, and thought the scandal might give them a third way. And Bannon and the Trump wing of the party saw a “drain the swamp” candidate who was as adamantly opposed to Republican Senate leader Mitch McConnell and to Democratic minority leader Chuck Schumer.

Victory for Doug Jones would shrink the Republican margin in the Senate to a pencil-thin 51-49 margin

Moore’s refusal to drop out and his inability to adequately rebut the allegations against him has framed the race as a referendum on him, with moderate establishment types caught in the middle between their loathing for a man accused of sexual misconduct and their traditional disdain of the Democratic party.

This divide has meant that Democrat Doug Jones has closed the gap, with the message that a Moore win would embarrass the state and make it more difficult for Alabama to attract jobs. He has not dwelt on major policy issues or deep ideological chasms. Instead, to residents of a state that was long a national punchline for its history of poverty and segregation, he has promised to simply represent them with honor. As one of Jones’s top surrogates, congresswoman Terri Sewell, has repeated: “We deserve to have a US senator we can be proud of, whose character will be unquestioned, whose integrity and veracity will be unquestioned.”

That message has resonated with some. Doris Anthony of Montgomery told the Guardian at a Jones event on Saturday that a Moore win would be an embarrassment for her home state. It would mean “we are off our gourds, that we are not able to make political decisions based on facts”. But to others, there were still plenty of reasons to vote for Moore.

The allegations initially turned the race into a dead heat or perhaps even a lead for Jones. But their impact has diminished as time passed. Democratic pollster Zac McCrary thought if the election had been held three weeks ago, Jones would have won comfortably. Moore strategist Brett Doster told the Guardian: “The allegations themselves had an impact when they first came out because people were dealing with shock effect.” However, Doster said he thought they had receded because “they are simply not true and there is not a shred of credible evidence to back them up”.

Many Republicans have agreed with the Moore strategist about the women who have come forward accusing Senate candidate of sexual assault. In a focus group done by pollster Frank Luntz for Vice News, Moore supporters dismissed the allegations as false. Luntz compared the support for Moore to that for Donald Trump in 2016. “It’s a level of intensity unprecedented in American politics,” Luntz told the Guardian. “Like Trump voters in 2016, the more you challenge them, the harder they fight back. And like Trump voters, they hate the opponent as much as they like their candidate.”

Even before the first allegations against him, Moore was long considered a fringe and unusual figure. He was first elected as chief justice of the state supreme court in 2000 and immediately decided to install an elaborate stone monument to the Ten Commandments inside his courthouse. Lawsuits ensued. Federal courts ruled that the monument violated the principle of separation of church and state. Moore defied the federal courts, refused to remove “Roy’s rock” and was himself removed from office.

After several unsuccessful bids for statewide office, Moore was re-elected to his old post in 2012. When the supreme court ruled gay marriage was legal in the United States in 2015, Moore attempted to instruct local officials that the decision didn’t apply in Alabama. After yet another federal court battle, Moore was forced out of office again. He seemed destined to be a forgotten cult figure, revered by rural Republicans but unable to gain sufficient suburban support in Republican primaries to ever become a significant figure. Then senator Jeff Sessions became Trump’s attorney general, and former governor Robert Bentley appointed attorney general Luther Strange to be his replacement.

Strange had been investigating Bentley for using state resources to cover up an extramarital affair – which forced him to resign from office and plead guilty two misdemeanors earlier this year. In a state with a reputation for political corruption that had seen several governors jailed and the first Republican speaker of house in a century convicted of felonies in 2016, Bentley’s appointment of Strange raised eyebrows. Several connected Republicans have speculated to the Guardian that if Strange ran for the seat on his own, he would have won easily – but the appointment doomed him.

The result was that Moore managed to pull off a victory in the Republican primary, despite Strange having the support of national Republicans and even a lukewarm endorsement from Trump.

Moore’s victory in the primary was the result of an odd alliance between the social conservatives who had long flocked to Moore’s banner and Trumpist populists – including former White House strategist Bannon, who simply rallied to anyone opposed by McConnell.

However, that alliance gave Democrats the opportunity to expand their coalition to “not just the typical Democratic base but so many women and moderate Republicans” as Sewell told the Guardian. In attempt to appeal to these swing female voters, Jones’s campaign offices featured homemade signs like “Women support Doug because Doug supports women.”

Just as Trump’s populist rhetoric alienated many suburban voters in 2016, it strikes an awkward tone in Alabama where the state Republican party only became relevant in the 1960s and 1970s in opposition to conservative Democratic populist George Wallace. Among these voters in prosperous Alabama suburbs, Moore was despised not just for the allegations against him but for his long history of inflammatory statements on social issues including his belief that “homosexual conduct” should be illegal and fervent tirades against “the transgenders”.

This distaste means that many Republicans will stay at home on Tuesday or vote for a write-in candidate if they cannot bring themselves to vote for the Democrat Jones. Richard Shelby, the state’s senior Republican senator, went on national television on Sunday morning to reiterate his opposition to Moore. “I didn’t vote for Roy Moore. I wouldn’t vote for Roy Moore. I think the Republican party can do better,” said Shelby. Instead, he voted for a write-in candidate. The statement was immediately turned into an advertisement by the Jones campaign.

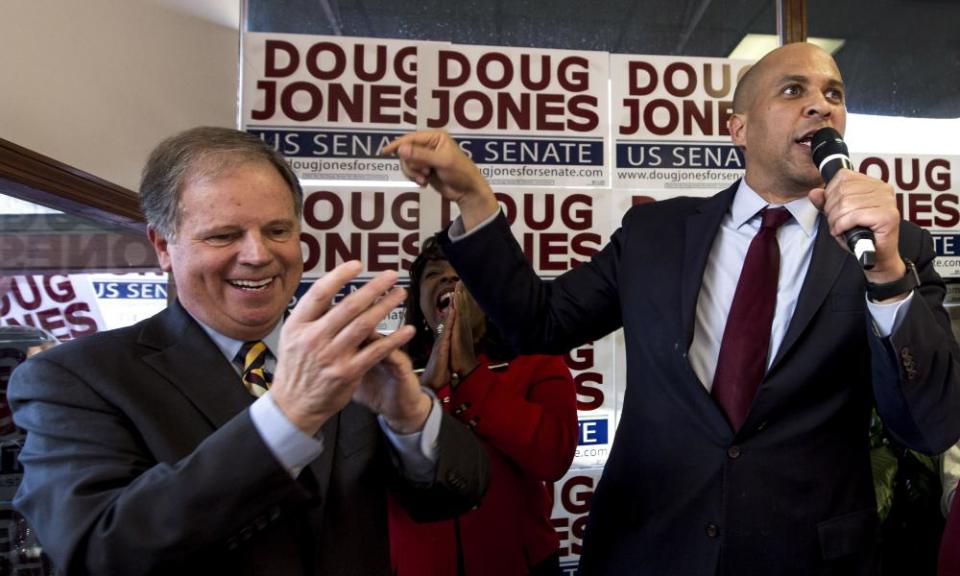

The challenge for Democrats is to not only convert moderate Republicans appalled by Moore’s record and the allegations against him, but to energize African Americans, who make up more than a quarter of the state’s population and a represent a reliable Democratic bloc. Although African American turnout increased significantly under Barack Obama, it fell nationally in 2016 for the first time in two decades.

In a state where race is deeply interwoven with politics – Moore’s election night event will be roughly halfway between the first capital of the Confederacy and the bus stop where Rosa Parks boarded in 1955 – African Americans vote for Democrats by 10 to one margins. The Jones campaign has been frantically working not to convince black voters to support them but to ensure that African American turnout is proportional.

Jones has spent much of the last few days stumping in the African American community and bringing in national African American surrogates. On Saturday, Jones first campaigned in front of the historic Brown Memorial Chapel AME Church in Selma with former Massachusetts governor Deval Patrick. He then went to Alabama State University, a historically black college in Montgomery with New Jersey senator Cory Booker.

Speaking to reporters in Selma, Jones dismissed concerns about his campaign’s outreach to black voters. “I feel very, very comfortable that we’ve been reaching everybody,” Jones said. “I want to make sure everyone understands this is not just a question about African American voters, this election is about everybody in the state.”

But while Jones is using some national Democrats as surrogates, many Republicans in Washington are condemning his opponent. Senator Cory Gardner, the head of the National Republican Senatorial Committee, said flatly that the political arm of Senate Republicans would never back Moore. “Roy Moore will never have the support of the senatorial committee,” said Gardner, a Colorado Republican. “We will never endorse him. We won’t support him. I won’t let that happen. Nothing will change.” Even more dramatically, Republican senator Jeff Flake of Arizona sent a campaign contribution to Jones the Democrat, tweeting a picture of the donation with the message “country over party”.

The only national Republican to back Moore has been the president. He openly backed Moore and gave him a wholehearted endorsement in a rally on Friday in Pensacola, Florida, just across the state line from Alabama. He has also recorded a robocall on Moore’s behalf. Trump, who has faced multiple allegations of sexual assault himself, even went out of his way to try to discredit one of Moore’s accusers.

But with the reluctance of most national Republicans to get involved, the race has become a key proving ground for Bannon’s crusade to transform the Republican party into a vehicle for his populist cause.

Bannon’s website Breitbart has wholeheartedly backed Moore as a fellow “economic nationalist” and used the race as an opportunity to build grassroots opposition to party leadership.

Andy Surabian, a close Bannon ally who is the senior advisor to the Great America Alliance Super Pac, said McConnell’s criticism helped Moore weather the allegations. “I think if Judge Moore wins on Tuesday, he should send Mitch McConnell a fruit basket, because if it wasn’t for Mitch McConnell and the Washington establishment trying to force Judge Moore out of the race there would be a greater chance of him not surviving.”

Surabian went on to crow that McConnell was now a hate figure “on par with George Soros” in the eyes of Republican primary voters.

In contrast, Jones has had to strike a delicate balance. In a state that Trump won overwhelmingly in 2016, Jones needs to appeal to more moderate Republicans to have a chance.

At a campaign office in Huntsville, where volunteers made calls in a packed office space on Thursday afternoon, the script to persuade undecided voters described Jones as “a bipartisan consensus-builder” who will “ensure the good people of Alabama are represented with dignity”. That messaging was reflected on the campaign trail, where Jones has campaigned on his ability to work with Shelby to deliver federal money to the state.

The consequences, though, are far more significant nationally than whether pet projects in Alabama receive federal funding. A win by Moore would represent a massive victory for the Bannon wing of the party, which is aiming to dramatically shift the Republican party and will launch primary challenges against several incumbent senators and find anti-McConnell candidates to win the Republican nomination in seats held by Democrats for next year’s midterms.

McConnell and his allies would paint a Jones win as the extremes of the party once again undermining its electoral fortunes, and would use it to bolster the case for establishment Republicans in 2018.

For Democrats, if Jones wins, it would shrink the Republican margin in the Senate to a pencil-thin 51-49 margin, and would mean only two Republican dissenters would be enough to stop Trump’s tax bill and any other White House goals on Capitol Hill.

If Jones loses, it simply means that they can go into 2018 elections painting the Republicans as the party of alleged child molesters in 2018. Democrats would prefer the former but, after an upside-down race in a deep red state, they would settle for the latter.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News