Here's why you don't enjoy blockbusters like you did

On the face of it, blockbusters are in rude health.

Box-office grosses can rival the GDP of small nations, Marvel and its ilk continue to create genuinely exciting franchises chock full of limitless possibilities, and again and again we find ourselves drawn back to the multiplex.

Deep down though, the way we enjoy these big cinematic events has changed. Even if you do successfully evade the minefield of trailers and teasers in the run-up to release, each one more spoilerific than the last, you may emerge from the cinema with the nagging feeling that it just didn't have the same impact on you as blockbusters once did.

Gently nodding along? Wondering why you didn't realise this earlier? There's more than one reason, and they're not as obvious as you'd think…

The science of getting it wrong

"Audiences are getting more discerning," says Tim Smith, a cognitive psychologist specialising in audivisual cognition at Birkbeck University. "We're no longer won over by the spectacle of CG imagery. But so long as our attention isn't drawn to the act of the construction of the image, we can let most imperfections go by."

And that's the trouble. While our gaze has remained the same – limited to 5% of the screen, occasionally shifting to view people's faces and points of high interest like explosions – CGI has not. No longer on the periphery, over time it's gradually moved front and centre, where we're faced to confront it for longer periods.

Stephen Prince, professor of cinema studies at Virginia Tech, notes that "cinematic representation operated significantly in terms of structured correspondences between the audio-visual display and a viewer's extra-filmic visual and social experience." (Translation: what we process on screen will always come back to logic.)

So, if an autobot happens to be on the screen, or King Kong – fine, we can deal with that. If Avatar is mostly CG, no problem. Issues arise when we process objects we wouldn't assume need digitalising.

Like, say, a human being – which prompts a dilemma within our moviegoing minds.

A case in point is the CG rebirth of the late Peter Cushing as Grand Moff Tarkin in the otherwise excellent Rogue One: A Star Wars Story. Even aside from the ethical question over thawing out a dead man's cinematic DNA, the character polarised opinion, largely due to the famous "Uncanny Valley" effect, whereby watching ultra-real – but not quite real – humanoid forms can elicit feelings of unease.

Cushing 2.0 was labelled a "constant distraction" by Collider and accused of "quietly undermining every scene he's in by somehow seeming less real than the various inhuman aliens in the movie" by The Hollywood Reporter.

(Don't expect the digital gravedigging to stop there: Ridley Scott has already hinted he could employ similar technology to de-age Sigourney Weaver – don't worry, she's fine – for future Alien outings, while it makes perfect commercial sense for studios to safeguard their franchises.)

Yet Hollywood's quest for digital perfection is also its weakness. For these dizzying spectacles to operate with the same jaw-dropping impact as they did a few decades ago, it would seem what's needed is a better balance between CG and practical effects.

Take Jurassic World. A great story, no doubt. A box-office behemoth, for sure – but did 2015's summer event really make you "hold on to your butt" as its 1993 forbearer did? No, no it did not.

While the CG employed in Steven Spielberg's 1993 original was certainly pioneering, much of the claustrophobic terror and joy was down to the work of SFX maestro Stan Winston, whose animatronics provided everything from those raptors running amok in the kitchen (eyes and arms were radio-controlled), to the sick triceratops wheezing like Homer Simpson with a hangover. Pure cinematic gold. Had these moments been purely CG, they'd likely have a considerably different feel.

Give Chris Pratt all the raptors you want – Jurassic World could never compete.

A misunderstanding in the brain

The film's apparent over-reliance on CG prompted YouTube science channel StoryBrain to release a video arguing why CGI peaked in the '90s. "Where CGI outweighs the physical in a film," they explain, "a misunderstanding occurs in the way the brain processes the visuals, leaving you unconcerned about the events on screen".

And make no mistake, we're getting much more than we used to.

A few decades ago, directors would superimpose CGI on a real scene – a trick that lasted up until around 2004, when software passed the point where production teams could render fully computer-generated backgrounds and foregrounds.

Dubbed the WETA effect (after the studio that pioneered it), it now meant entire worlds could be created without a director needing to pick up a camera, making the real action secondary and, subconsciously for the filmgoer, leading to a distinct lack of peril. You can see it in The Lord Of The Rings films, and even more obviously, in their Hobbit prequels.

Another major problem of this WETA effect, argues Tim Smith, is that the ease of creating CG worlds means filmmakers tend to show too much, in effect "taking away the mystery, and stopping the viewer from actively, cognitively engaging with the construction of the film in their own mind".

One man who gets it right more times than not is director Jon Favreau. Invited by the Academy of Motion Pictures to speak in a series of talks about CG in LA last year, Smith sat down with Favreau to conduct a live-audience experiment.

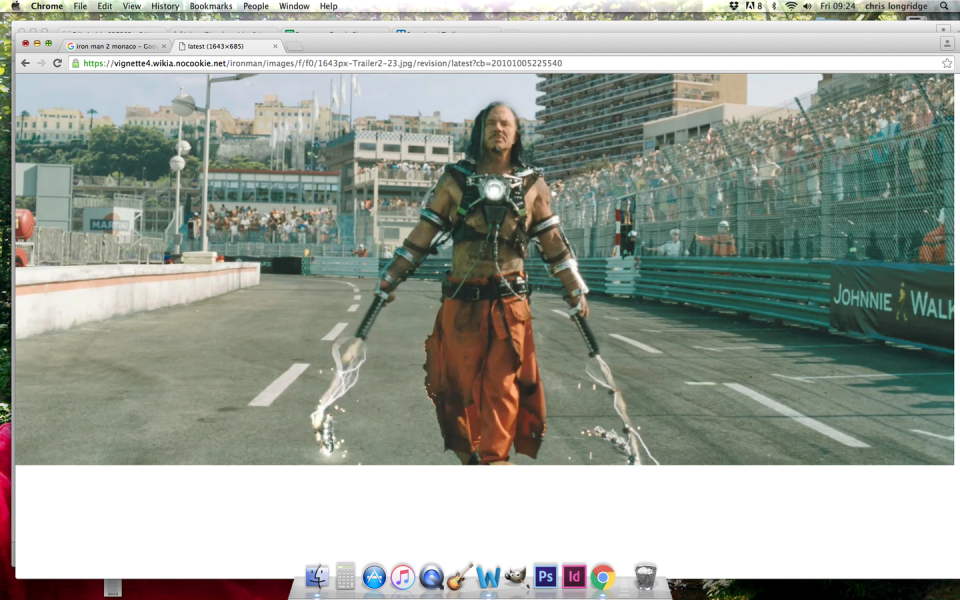

Tracking the eyes of how people watched the Monaco Formula One sequence in Iron Man 2, the aim was to see if viewers were looking at the areas Favreau had expected them to.

"He was quite surprised at how reduced the gaze was, how focused it was to a particular point on the screen, which was exactly the point he had composed his shots for," says Smith.

Meaning the background stayed in the background. "The majority of the CGI was in the periphery, exactly where the audiences weren't looking. Jon told us that they never even went to Monaco, that they shot on a backlot in LA. The crowd was basically a composite of multiple people, the cars are mostly CG. There's very limited real content in that scene, yet Jon made sure what real elements they did have were central, because he knew what things are going to attract the human eye."

So it's not just how much CGI is on screen that threatens our enjoyment of blockbusters, but rather where and how it's deployed.

You know when you've been Tango'd

You may have noticed that movies kind of, sort of, look quite similar these days. Not in the sense of "All Marvel films end with semi-robotic horde attacking a city from the sky", but in a more subliminal way. The advent of digital colour grading (whereby you can tint every frame of the film after shooting, adjust its brightness, boost the reds and so on) has allowed film-makers to seek out the optimum palette for their films.

One of the earliest, most distinctive uses of the technology was the Coen brothers' O Brother, Where Art Thou?, in which they changed all the greenery on show into a mellow, golden sepia, evoking the hot, Southern summers seen in old photographs. The Wachowskis turned everyone in The Matrix green. (They take on a much more naturally bluish daylight tint in the real-world scenes.)

But by far the most far-reaching consequence is known as the "orange and teal effect". In a nutshell, human skin looks at its best in a warm, orangy light. It's why old-school cinematographers always shot their romantic scenes in "magic hour" at dawn or dusk. And as any colour theorist knows, orange's complementary colour is teal (or subdued turquoise). Orange never looks as orange as when it's on a background of teal.

In short, films are literally all beginning to look the same.

The culture clash

Oh yeah, and there's also another factor at play in our declining excitement at tentpole pictures – quite a major one. "By their very definition, blockbusters are money-makers, and so have to fight for attention," says Smith. "So as films target international markets such as China and India, where language and characterisation can confuse, there will tend to be this simplification of those stories".

That's right: as blockbusters shift towards lucrative new shores, so too do the storylines. Action becomes the universal language, reducing the threat of culture-clash and narrative confusion, and the story – or what's left of it – becomes geographically ambiguous. Hence the "humans vs sea creatures" smashy-smashy spectacle of Pacific Rim, and Kong: Skull Island's cynical casting of a Chinese actress, Jing Tian, in a role nobody quite remembers.

If nothing else, at least these marketing ploys shed much-needed light on the soulless feel of the recent Transformers films – their human element now all but lost to a CG orgy of Dino-bots, exploding oil drums and wanton product placement.

Age of Extinction? Perhaps Michael Bay meant his prop team…

Want up-to-the-minute entertainment news and features? Just hit 'Like' on our Digital Spy Facebook page and 'Follow' on our @digitalspy Twitter account and you're all set.

You Might Also Like

Yahoo News

Yahoo News