Arched feet essential for walking ‘evolved in humans 3.5 million years ago’

Humans evolved to have a “unique” arch across each foot more than 3.5 million years ago which enabled walking and running on two legs, scientists have said.

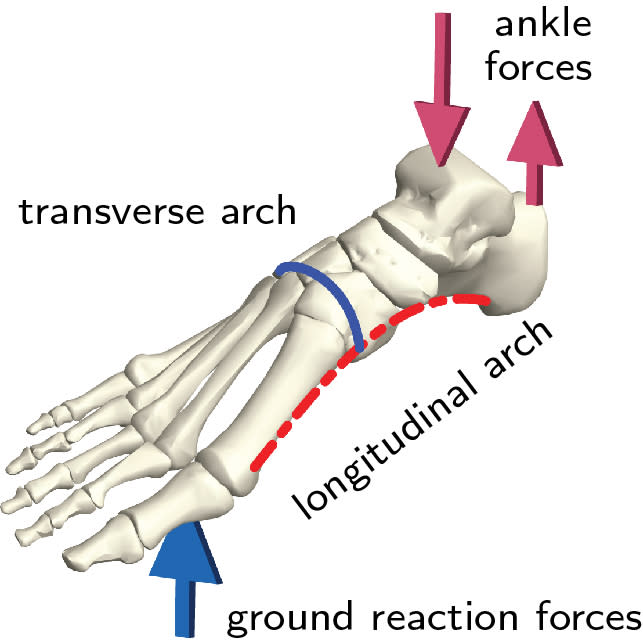

The so-called transverse arch, which run across the width of the midfoot, is absent in other primates such as chimpanzees and gorillas which have flat, and more flexible, feet.

The scientists believe their findings, published in the journal Nature, show a “key step” in human evolution and may help to improve the design of robotic feet.

Madhusudhan Venkadesan, an assistant professor at the Yale School of Engineering and Applied Science in the US, and one of the lead authors on the study, said: “Our evidence suggests that a human-like transverse arch may have evolved over 3.5 million years ago, a whole 1.5 million years before the emergence of the genus Homo, and was a key step in the evolution of modern humans.”

Mahesh Bandi, an associate professor at the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology Graduate University in Japan, who co-led the study, added: “Having a firm understanding of how the human foot works has several real-world applications.”

Anthropologists have long debated how the structure of the human foot creates the stiffness that is essential for upright walking.

While most studies have focused on the longitudinal arch, which runs from the heel to the ball of the foot, the role of the transverse arch has been overlooked.

To investigate whether the transverse arch creates stiffness, a team of engineers, which included scientists from the University of Warwick, performed bending tests on human feet and examined fossil samples of human ancestors and relatives.

They also created computer simulations and plastic models of the midfoot and measured how much force was required to bend them.

Results showed the transverse arch to be responsible for “more than 40%” of foot stiffness.

Professor Bandi said: “We found that the plastic models and simulations with more pronounced TAs (transverse arches) were stiffer and less susceptible to bending than flatter ones.

“In contrast, on these models, an increase in the curvature of the LA (longitudinal arch) had little effect on the stiffness.”

Just as bending a sheet of paper parallel to the width stiffens it lengthways, the researchers believe the transverse arch may have a similar role in feet.

Dr Shreyas Mandre, from the department of maths at the University of Warwick and the study co-leader, said that flat thin objects like paper sheets bend easily, but are much more difficult to stretch.

He added: “The transverse curvature of the sheet engages its transverse stretching when attempting to bend it.

“This coupling of bending and stretching due to curvature is the principle underlying the stiffening role of the transverse arch.”

The team believe their findings may explain how Australopithecus afarensis, a human relative which lived around 3.66 million years ago, could generate footprints like humans, despite having no apparent longitudinal arch.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News