'Atomic plague': how the UK press reported Hiroshima

On August 7 1945, few Britons expected the war to end soon. The relief of VE Day three months earlier had already faded. Thousands of British soldiers, sailors and airmen were still involved in gruelling battles against Japanese imperial forces. Many who had fought across Europe expected to be sent to join them.

On Okinawa, American forces had lost 10,000 in their campaign to expel the Japanese garrison. A Sunday Times correspondent wrote that:

The protracted and extremely bitter fighting and the substantial casualties incurred by the attackers convey the obvious warning that the invasion of the Japanese homeland, if and when it comes, may be a very tough and expensive affair.

So, the reports about the attack on Hiroshima the previous day came as a complete surprise. My research into newspaper archives, only available electronically by subscription, reveals that journalists were stunned by the scientific breakthrough.

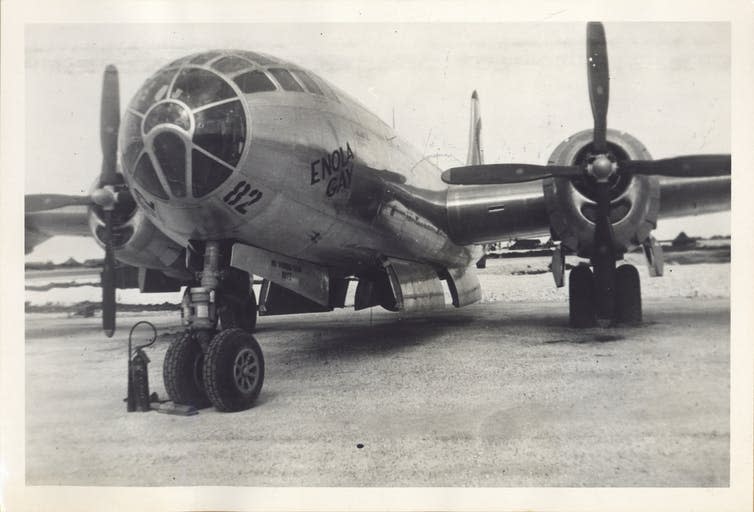

The Manhattan Project, whose team of American, British and Canadian scientists had designed and assembled atomic bombs at the Los Alamos laboratory in New Mexico, was an intensely guarded secret. Beyond a tiny elite, the weapon that would “radically alter the military and diplomatic power of the USA” and define the strategic politics of the post-war world, was unheard of and unimagined.

The Manchester Guardian’s initial report of the Hiroshima bomb explained that it was the result, as its headline related, of “Immense Co-Operative Effort by Ourselves and US”. A combination of awe at the scientific achievement and patriotic pride united newspapers of left and right.

From New York, the Daily Mail’s James Brough predicted that Japan faced obliteration by “the mightiest destructive force the world has ever known – unless she surrenders unconditionally in a few days”. A second report told how the workers who built the bomb had never seen their final product “and until today, they did not know what they were doing”.

Just days later, The Times correspondent in Washington DC explained that Japanese resistance had shaped the decision to attack Hiroshima:

Until early June, the president and military leaders were in agreement that this weapon should not be used … but those responsible came to the conclusion that they were justified in using any and all means to bring the war in the Pacific to a close within the shortest possible time.

Beyond belief

But, amid astonishment at the new weapon, concern was not entirely buried. Winston Churchill wrote in the Daily Mail that: “This revelation of the secrets of nature, long mercifully withheld from man, should arouse the most solemn reflections in the mind and conscience of every human capable of comprehension.”

The Daily Mirror sought to make sense of the weapon’s power by relating it to its readers’ own lives. In a fine example of quality popular journalism, commissioned just 24 hours after the first bomb fell, the Mirror asked its reporters to explain what would have happened if an atomic bomb had hit their city.

From Edinburgh, the Mirror reported that: “All historic Edinburgh would have disappeared.” In London: “There would be a swathe of utter destruction from Kensington Church to the Mansion House, as wide as the parks and the West End, from Bayswater Road and Oxford Street, across to Piccadilly and the Strand.” Manchester believed everything between Victoria Station and Old Trafford would be levelled.

The Manchester Guardian’s London correspondent lamented: “The fact, so suddenly and appallingly revealed to us, is that we have devised a machine that will either end war or end us all.” The Listener, a weekly title owned by the BBC, prayed that work to maintain peace would be pursued with as much vigour as the science that had split the atom. Newspapers hoped the new technology would be used to generate cheap energy.

Hair-trigger business

Eyewitness accounts of the condition of survivors poisoned by radiation were slow to emerge. Wilfred Burchett’s account for the Daily Express, headlined “Atomic Plague”, was published on September 5. The authorised eyewitness account of the second, Nagasaki bombing, by William L Laurence for the New York Times was released on September 9. These would change the tenor of debate.

The Guardian’s London correspondent described people wondering how the capital “would have stood it had the Germans been first with the atomic bombs. What a hair-trigger business the world has become”.

In early September, the Daily Mail reported that Japanese doctors in Hiroshima were seeing patients die “at the rate of about one hundred daily through delayed action effects of the atomic bomb”. The Times reported warnings that: “No state would be more at the mercy of any future atomic bomb attacks than Britain” which had “immense aggregations of people in its great cities”.

Concern about the consequences of atomic warfare emerged more rapidly in newspapers than any about conventional bombing of German or Japanese cities. This had killed more civilians. Within weeks of the bombings, British newspapers had raised questions about how future use of atomic power might be effectively controlled and whether it could be used for peaceful purposes.

Read more: VE Day as reported by British newspapers: relief, joy and a saucy comic strip

Japan raised the question of moral culpability. “This is not war, not even murder, it is pure nihilism”, declared its state broadcaster. Such responses begin to explain why, eight decades later, few Germans challenge their nation’s war guilt, but many Japanese consider their country a victim as much as a perpetrator of war.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Tim Luckhurst has received research funding from News UK and Ireland Ltd. This article is based on research conducted in preparation of my book under the provisional title 'Reporting the Second World War: Newspapers and the Public in Wartime Britain'. I am under contract to Bloomsbury Academic, an imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

Yahoo News

Yahoo News