Australian government acted with 'hubris' before Victoria's aged care outbreak, inquiry told

The federal government acted with “self-congratulation” and “hubris” by not learning lessons and not preparing Victoria for its devastating outbreak of coronavirus in aged care, a royal commission has heard.

The counsel assisting the commission, Peter Rozen QC, delivered the strong criticism in his closing remarks to a week of emergency hearings, called to examine how the coronavirus pandemic entered Australia’s nursing homes.

So far there have been 220 deaths of aged care residents due to Covid-19, which makes up 70% of the nation’s deaths.

The commission also heard:

The government acted too late in only making masks compulsory for aged care workers on 13 July – after a person had already died in Victorian aged care, and months after people had died in New South Wales.

Blanket bans on visitors into aged care homes should be lifted “in all but extreme cases”.

The mask advice was so confusing that it “appeared to be [done] by press release”.

The former chief medical officer, Prof Brendan Murphy, could not identify what legal order had made masks compulsory.

Rozen said that the federal government, which has responsibility for private aged care homes, failed to learn the lessons of earlier Covid-19 outbreaks in NSW.

Related: Victoria takes control of three more aged care homes as 278 new Covid cases recorded

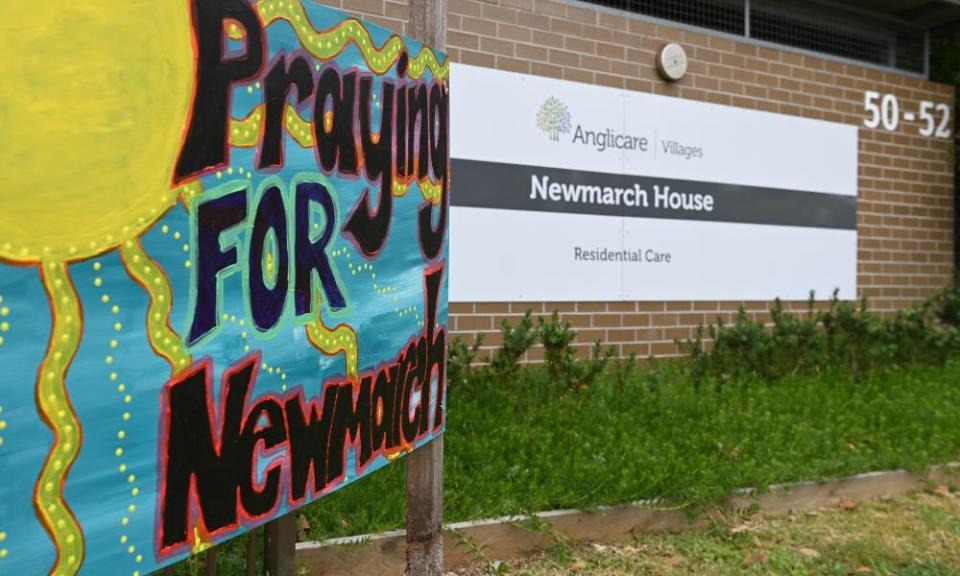

Dozens of people died during outbreaks at the Newmarch House and the Dorothy Henderson Lodge facilities, until they were brought under control in April. However, in mid-June, outbreaks began in Victoria’s private aged care homes, many of which are still continuing, and have led to more than 200 deaths.

Rozen told the commission that the lessons from NSW had not been learned, and that aged care was still “not properly prepared now”.

“Tragically not all that could be done was done,” he said.

“There is reason to think that in the crucial months between the Newmarch House outbreak in April and mid-June a degree of self-congratulation and even hubris was displayed by the commonwealth. Perhaps they were reflecting the general mood in the country that we were through it.

“The time between the two Sydney outbreaks and the increase in community transmission in Melbourne in June was an important period ... What did the commonwealth do to ensure the lessons of the two outbreaks were conveyed to the aged care sector? We say it’s not enough.”

He also said Australia acted too late making masks compulsory and criticised the former chief medial officer, Prof Brendan Murphy, for not being able to say whether the peak emergency health body – the AHPPC – had even discussed compulsory masks.

Rozen said that the advice around masks was so confusing that it “appeared to be [done] by press release”.

He criticised Murphy, who gave evidence earlier in the week, because Murphy could not say what legal order had made masks compulsory.

“Prof Murphy was not sure and thought it might have been a Victorian public health order,” Rozen said. “He said he would have to check, we are awaiting the outlook of that checking.”

Related: Australian experts warn against the use of sedatives to contain Covid spread in aged care

Michael Lye, who is the deputy secretary at the federal health department, also could not answer the question, Rozen said.

“Mr Lye was not necessarily sure it was such an order. This level of confusion by senior officers in the Department of Health is far from reassuring, it appears to be more by press release.”

He also said he believed the 13 July decision was made “on the run”, and was sparked by the death of a resident in Victorian aged care, rather than a plan from health authorities.

“Prof Murphy and Mr Lye were unable to clarify if there had been discussions within the AHPPC regarding making mask wearing compulsory any time between 16 June and 13 July,” he said. “One is left with the sense that it was the death of an aged care resident on 11 July, the first in the current outbreak, that prompted the advice.”

Later, Rozen also recommended that any blanket bans on visitors into aged care homes should be overturned.

He pointed to evidence from earlier in the week from experts who said they were “not aware of any cases where visitation has resulted in a case of Covid-19 within a facility”.

Earlier this week, the commission heard from a woman, given the pseudonym UY, whose father had died in an aged care home in Victoria in May, before the state’s second outbreak.

She told the commission she “begged” to be able to take her father for walks, and when she did, she noticed he had visibly deteriorated without visitors.

Her father was “an Italian man for whom family was everything” and who had dementia, meaning he “relied on physical touch to communicate”, Rosen said.

The woman told the commission that “Dad gave up wanting to live” as a result of his lack of visitors and died in his sleep.

“We submit that a blanket ban on visitation is unacceptable in all but extreme cases,” Rozen said.

In his closing statements, he told the commissioners, Lynelle Briggs and Tony Pagone, that Australia had become one of the worst-performing countries in the world in aged care deaths.

He said multiple reports and experts had sounded the alarm over Covid-19.

“The federal government, which has sole responsibility for aged care, was firmly on notice early in 2020 about the many challenges the sector would face if there were outbreaks of Covid-19,” he said.

“Firstly, the limitations of the aged care workforce have been well documented in reports such as the 2018 report of the aged care workforce taskforce. The sector is understaffed and it lacks nurses with clinical skills.

“Secondly, it was widely report in both Europe and New York, America, residents were dying in nursing homes as a result of Covid-19. Thirdly, the interim report of this royal commission in 2019 revealed a range of problems that beset the sector … and finally individuals like Prof Ibrahim and organisations like the Nursing and Midwifery Federation had raised their concerns about the sector’s lack of preparedness for Covid-19 and had offered solutions.”

Yahoo News

Yahoo News