The Australian parliament, the whole arse-covering and ego-driven apparatus, should be paralysed by shame and remorse

The Jenkins review into parliament’s culture should make everyone, not just women, weep. But Scott Morrison is responsible for making change – this reckoning presented on his watch

There are statistics, and there are vignettes in Kate Jenkins’ review that trigger deep revulsion.

“The MP sitting beside me leaned over. Also thinking he wanted to tell me something, I leaned in. He grabbed me and stuck his tongue down my throat. The others all laughed. It was revolting and humiliating.”

Another person said there were aspiring male politicians “who thought nothing of, in one case, picking you up, kissing you on the lips, lifting you up, touching you, pats on the bottom, comments about appearance, you know, the usual. The point I make with that … was the culture allowed it, encouraged it.”

Another: “Frequently, like at least every week, the advice was go and cry in the toilet so that nobody can see you, because that’s what it’s like up here.”

Parliament is not the only Australian workplace where women, and some men, feel unsafe. There are plenty of toxic places, plenty of terrible stories.

But there are distinctive characteristics of political life that supercharge some of the risks. The Jenkins review lists them. The role of power, gender inequality, a lack of accountability, a culture of entitlement and exclusion.

I sit on the edge of this world. I have for more than two decades. Political reporters are in it, and out of it. The hours are long. We all work under high pressure. The occupational requirements are unforgiving. Perfection is a high bar, and I certainly don’t claim to clear it.

But if any external agency assessed my own news bureau in the terms in which the sex discrimination commission has just reviewed the parliament, I would dig a large hole, clamber inside, and never get out again.

I would be paralysed by shame and remorse. I would feel the clinical rebuke in my marrow. There would not be enough ways of saying sorry.

A review like the one tabled on Tuesday should trigger deep institutional atonement (which was actually recommendation one of the Jenkins report: stop, take a beat, acknowledge the wrong).

The women who spoke to the human rights commission about their private humiliations, people who have spent years being angry, should not be the only ones weeping.

The Australian parliament, the political class, the whole arse-covering, ego-driven apparatus, should care enough to grieve.

It should care enough to want to be better.

But almost immediately after the Jenkins review was made public, someone in the Senate made a noise that sounded for all the world like a dog growling when the Tasmanian independent Jacqui Lambie was on her feet asking a question.

The growl (or growl-adjacent sound – the Liberal senator who made it later contested it was a growl while apologising “unreservedly” to Lambie for the interjection) wasn’t audible on the internal broadcast.

But the Greens senator Sarah Hanson-Young and Labor’s Senate leader, Penny Wong, heard it clearly, and said it came from the government side of the chamber. Both objected in the strongest possible terms.

While the Senate did pause momentarily to consider this development, nobody confessed immediately to inappropriate growling, so the Senate moved on – because why would the Senate become paralysed by introspection?

As the Jenkins review notes, politicians don’t have conventional employers to account to. They can growl while a woman is talking without being reported to the nonexistent human resources department, and later contest the precise nature of the sound while promising to be better. Tomorrow obviously. Being better always happens tomorrow, or possibly the next day.

The house was also in a mood. The testosterone was so thick and so noxious the new Speaker, Andrew Wallace, must have felt at risk of choking.

After an extended rhetorical maul – hackles raised, chests out, voices raised, like unruly teenagers on the verge of a schoolyard brawl, man toddlers separated by Perspex screens – Anthony Albanese branded Peter Dutton a “boofhead” and shouted at him to sit down while Dutton accused the Labor leader of having a “glass jaw”.

Email: sign up for our daily morning briefing newsletter

App: download the free app and never miss the biggest stories, or get our weekend edition for a curated selection of the week's best stories

Social: follow us on YouTube, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter or TikTok

Podcast: listen to our daily episodes on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or search "Full Story" in your favourite app

Shortly after this inspiring interlude, Wallace reminded MPs the just-released Jenkins review had called for “respect”.

“As I said in my first speech as Speaker, I don’t expect this place to be a monastical library, but the Australian public does not want to see this place descend into a political colosseum,” Wallace counselled. “There will be a lot of discussion over the next days and weeks over respect in this place and I would ask members, all members, to show that level of respect in this chamber as well.”

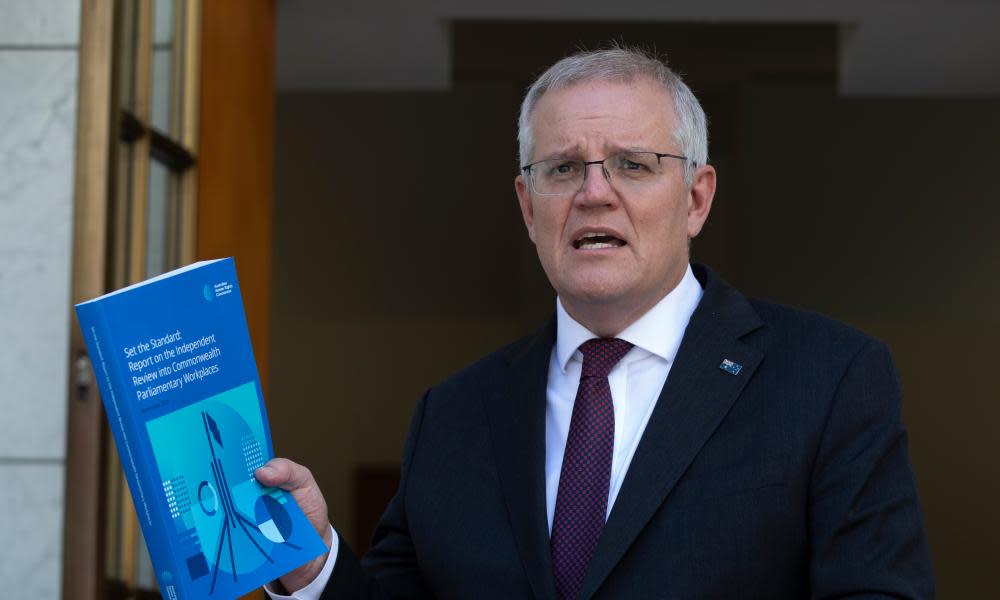

Before question time, we had Scott Morrison in his courtyard, being appalled, yet also not surprised, about the culture depicted by the review.

Morrison didn’t say anything terrible. It wasn’t like those excruciating weeks after the former Liberal staffer Brittany Higgins came forward with her allegation of sexual assault – an allegation that blew the lid right off the often dysfunctional and sometimes cruel enterprise of working in the belly of the political beast. Back then, every word the prime minister uttered was wrong.

Tuesday’s words were better, but just like with the Higgins matter, Morrison was also flat out managing, massaging, shaping.

The prime minister’s very obvious objective immediately on receipt of the report was to make sure that nobody concludes this grossness is a Coalition problem, or a government problem.

This muck was everybody’s problem. Liberals, Nationals, Labor, Greens, journalists. The prime minister thought this crook culture had been around for a long time – certainly longer than he’d been in the parliament. Everyone had a role in the clean-up.

Morrison is correct to say everyone has a role in the clean-up. We are all culpable in our own spheres for knowing about these things, or a version of these things, but moving too quickly past them.

But the problem with everybody being responsible is it is too easy for no one to be responsible, particularly when the reform options get hard, and some of the proposed changes will be contentious.

Jenkins has given the parliament a structure to work with when it comes to attacking the root causes of some of the problems.

But the measure of success will be action – and prompt action. This review is a landmark, but plenty of landmarks gather dust.

Going forward, Morrison needs to understand two things.

The first is he is responsible for making this change. He is the prime minister who has to build the necessary consensus to get this done. This moment of reckoning has presented on his watch.

The other thing Morrison needs to understand is we are watching. We owe it to the victims of this crook culture to go on watching. The prime minister will be judged by what he delivers.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News