Awe, wonder and the overview effect: how feeling small gives us much-needed perspective

Surely the best witnesses to the fact that the key to awe and wonder is feeling small are astronauts. Like Captain Jim Lovell, who, when on board the Apollo 8 on Christmas Eve 1968, raised his hand against the window and watched the entire planet disappear. “I realised how insignificant we all are if everything I’d ever known is behind my thumb,” he said. The first person to ever step on to the moon, Neil Armstrong, did exactly the same thing. He recalled later: “It suddenly struck me that tiny pea, pretty and blue, was the Earth. I put up my thumb and shut one eye, and my thumb blotted out the planet Earth. I didn’t feel like a giant. I felt very, very small.”

We have shot hundreds of human beings into space over the past few decades, most with a background in engineering, science, medicine or the military, and almost all of them seem to return with permanently widened eyes. Former soldiers suddenly speak of elation, mathematicians of bliss, biologists of transcendence. The term for the psychological impact of flying into space and viewing the Earth as a simple dot is called the “Overview Effect”, and it was coined by author Frank White in his book of the same name in 1987. White defined it as “a profound reaction to viewing the Earth from outside its atmosphere”.

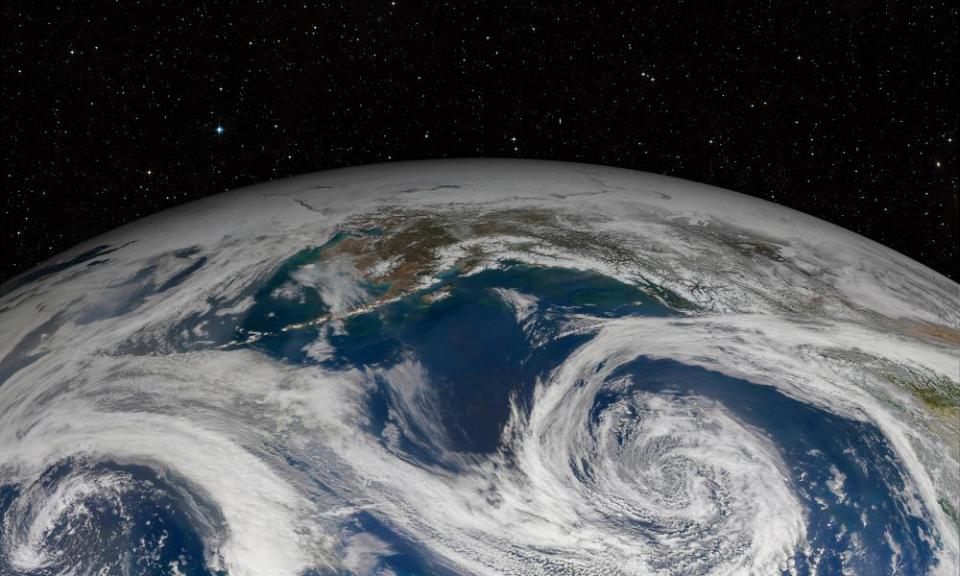

The Overview Effect turns astronauts into “evangelists, preaching the gospel of orbit” as they return from space with a renewed faith or on a quest for wisdom. For some it’s a kind of lingering euphoria that results in a permanent change of perspective. The first human to reach outer space, the Russian cosmonaut, Yuri Gagarin, who circled the Earth for 108 minutes in 1961, came back with a clarion call: “Orbiting Earth in the spaceship, I saw how beautiful our planet is. People, let us preserve and increase this beauty, not destroy it.”

In recent years, scientists have been trying to measure and understand the Overview Effect, even sending people into virtual space, where they view galaxies through portals, and then grilling them about their responses, but the accounts of astronauts provide the best insights. The words they use are saturated with awe, an understanding of how fragile the Earth is, with its paper-thin atmosphere, and how much needs to be done to protect it and its inhabitants.

As Syrian astronaut Muhammad Ahmad Faris said, when you look at Earth from space, the “scars of national boundaries” disappear. American Sam Durrance said he became emotional after having hurtled past the stratosphere into black space because “you’re removed from the Earth but at the same time you feel this incredible connection to the Earth like nothing I’d ever felt before”. Mae Jemison, the first black woman to travel in space, who orbited the Earth 127 times in 1992 on board the space shuttle Endeavour, also says she felt “very connected with the rest of the universe”. (She later told students: “Life is best when you live deeply and look up.”)

The Japanese term yugen, which derives from the study of aesthetics, is sometimes used to describe space-gazing. It is said to mean “a profound, mysterious sense of the beauty of the universe … and the sad beauty of human suffering”, though the meaning and translation depend on the context. Japanese actor and aesthetician Zeami Motokiyo described some of the ways to access yugen:

To watch the sun sink behind a flower-clad hill.

To wander on in a huge forest without thought of return. To stand upon the shore and gaze after a boat that disappears behind distant islands. To contemplate the flight of wild geese seen and lost among the clouds.

And subtle shadows of bamboo on bamboo.

Or to stare at the heavens from Earth, or Earth from the heavens.

Yugen is also defined as “an awareness of the universe that triggers emotional responses too big and powerful for words”. It’s striking how, repeatedly, people who venture into space speak of the inadequacy of words. Former Nasa astronaut Kathryn D Sullivan, who in 1984 became the first woman to ever walk in space (and in 2013 was nominated by president Obama to be under secretary of commerce for oceans and atmosphere), was also gobsmacked.

“It’s hard to explain how amazing and magical this experience is,” she says. “First of all, there’s the astounding beauty and diversity of the planet itself, scrolling across your view at what appears to be a smooth, stately pace … I’m happy to report that no amount of prior study or training can fully prepare anybody for the awe and wonder this inspires.”

American engineer and astronaut Nicole Stott reported that she was “stunned in a way that was completely unexpected”. She described it to her seven-year-old son this way: “Just take a lightbulb – the brightest lightbulb that you could ever possibly imagine – and paint it all the colours that you know Earth to be, and turn it on, and be blinded by it.”

When you shrink, your ability to see somehow sharpens. When you see the beauty, vastness and fragility of nature, you want to preserve it. You see what we share, and how we connect. You understand being small. Astronaut Boris Volynov said that after seeing Earth from black space “you become more full of life, softer. You begin to look at all living things with greater trepidation and you begin to be more kind and patient with the people around you.”

Scott Kelly, who spent a full year on the International Space Station from 2015 to 2016, delighting Earth-dwellers with his tweets and superb photographs, told Business Insider that the experience of space makes people more empathetic, “more in touch with humanity and who we are, and what we should do to not only take care of the planet but also to solve our common problems, which clearly are many”. Kelly’s insights echo those of many others: the splendour and vulnerability of the Earth, the connectedness of people, and the need to work in concert, across nations. He said:

“The planet is incredibly beautiful, breathtakingly beautiful. Having said that, parts of it are polluted, like with constant levels of pollution in certain parts of Asia. You see how fragile the atmosphere looks. It’s very thin. It’s almost like a thin contact lens over somebody’s eye, and you realise all the pollutants we put into the atmosphere are contained in that very thin film over the surface. It’s a little bit scary actually to look at it.

And then you realise looking at the Earth, that despite its beauty and its tranquility, there’s a lot of hardship and conflict that goes on. You look at the planet without borders, especially during the day. At night you can see countries with lights, but during the daytime it looks like we are all part of one spaceship, Spaceship Earth.

And we’re all flying through space together, as a team, and it gives you this perspective – people have described it as this ‘orbital perspective’ – on humanity, and you get this feeling that we just need to work better – much, much better – to solve our common problems.”

The first Canadian to walk in space, Chris Hadfield, says whizzing across continents and seeing a sunrise or sunset every 45 minutes creates “a feeling of privilege and sort of a reverence, an awe that is pervasive. And that sense of wonder and privilege and clarity of the world slowly shifts your view.” He believes the Overview Effect is not limited to spaceflight but is more about “when you sense that there is something so much bigger than you, so much more deep than you are, ancient, [that] has sort of a natural importance that dwarfs your own.” This understanding, Hadfield suggests, can lead people to make smarter global decisions, and less “jealous, local, narrow” ones. We hope.

One of my favourite scientists is the brilliant Carl Sagan, an eloquent speaker, prolific author and cosmologist who was known in America as “the astronomer of the people”. He studied extraterrestrial life and sent physical “universal” messages into space in the hope that other beings might find and understand them. In his 1994 book Pale Blue Dot, which is about the solar system and our place in it, Sagan wrote about the sight of Earth from space.

He perfectly described how that view makes us keenly aware that our little planet is just a pale blue dot floating in an immensity of space, and our only home, where we and everyone we love, and everyone who has ever lived, has spent their lives. And he pointed out that recognising that all of humanity’s creation, and millennia of delight and pain, of hubris and striving, have all taken place on this tiny, distant speck must surely help us realise the importance of being decent and careful with each other, and of protecting and loving the Earth.

If only we could immediately send all members of our governing bodies, politicians and judges and thinkers, into outer space – and allow them to eventually return – to instil in them the urgency of protecting our planet.

You don’t have to leave this blue dot to experience awe, wonder and the like; but the accounts of mystified astronauts remind us of the importance of being alive to it, to open every door, window, threshold and portal to its possibility.

This is an edited extract from Phosphorescence – on awe, wonder and things that sustain you when the world goes dark, by Julia Baird (Fourth Estate, $32.99)

Yahoo News

Yahoo News