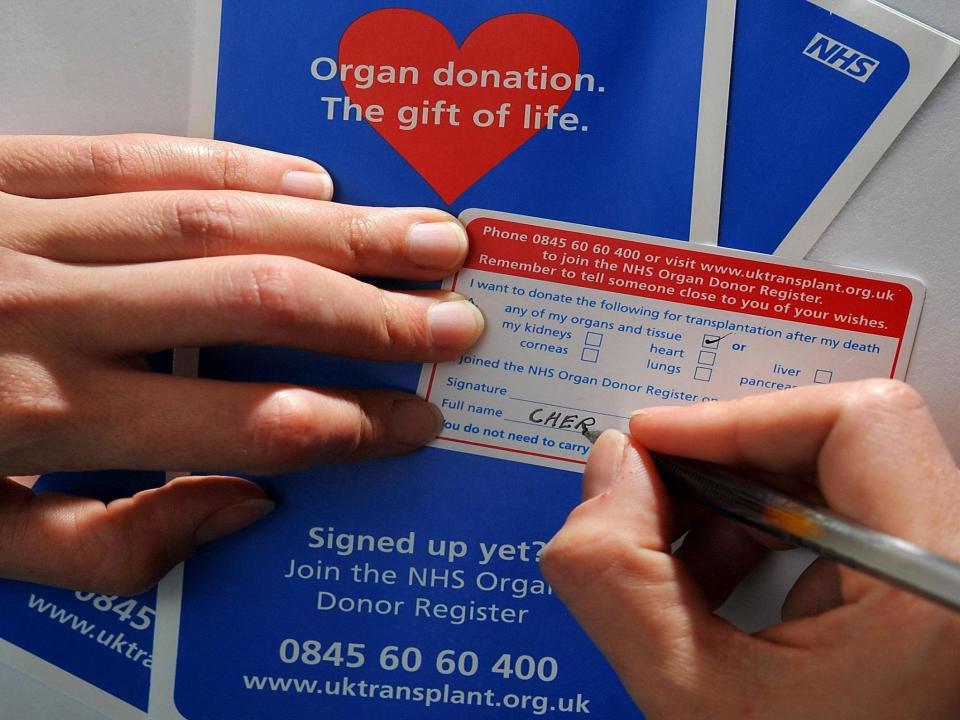

BAME groups are dying over religious falsehoods about organ donation. Why aren’t faith leaders helping?

Deciding whether or not to donate your organs after death probably rarely crosses the average person’s mind.

If you’ve never known someone in need of a life-saving organ transplant you may not be aware of the NHS’s desperation for organ donors. And if you’re not black or Asian you’re unlikely to know that BAME patients have to wait significantly longer than white patients for organs to become available.

Over the next year conversations about organ donation will become more common, as from 2020 adults in England will have to actively opt out of being on the potential donor register.

This news might have offered some hope for the BAME community, who, as a result of disproportionately low donor rates, have borne the brunt of racial disparity in transplant waiting times.

But a report published this week by the London Assembly suggests that it’s going to take serious and organised efforts over the next year to change BAME attitudes to remaining on the organ donor register, and it is our faith leaders who need to take charge of leading the conversations we need to make a difference.

Successful matches for organ transplants are more likely between people of the same ethnic group, so low rates of BAME people giving their consent to donate after death has a direct impact of how long other BAME people in need of organs will wait.

In a survey of BAME Londoners accompanying the report, it was revealed that concerns about religious conflicts held black and Asian people back from donating organs.

Of the people surveyed, 51 per cent who were unwilling to donate organs said it was because of their religious beliefs and 19 per cent said it conflicted with their cultural beliefs.

It’s not surprising that faith and culture are the biggest factors affecting organ donation. But what was striking was how much confusion there was about religious teachings among those who were surveyed.

Nearly a quarter of people who said they were unsure about organ donation said they might agree to it if someone from their faith or community group encouraged them to donate, and the same amount said they did not know whether their religion permitted organ donation or that they did not know enough about the subject.

It goes without saying that religious objections to organ donation should be respected like any other individual moral choice, and there will be people who opt out of the register for reasons that have nothing to do with faith. It’s a very personal decision.

But where there is confusion around the act of organ donation, faith leaders have a duty to give clear guidance, especially as some religions either sanction it or leave the matter open to personal interpretation.

Certain principles within Judaism can be interpreted to encourage organ donation while within Buddhism there is nothing set out either for or against. Sikhism and Hinduism both offer teachings that can be applied quite directly in favour of organ donation. And within Christianity and Islam there are many schools of thought that both support and prohibit donating organs.

If there are large amounts of people who might have considered staying on the register, but who opt out next year because they’ve had no access to reliable information about the teachings of their faith, this will have a massive impact on an already critical situation.

National figures from the NHS show that last year 21 per cent of people who died while waiting for an organ to be donated were black or Asian despite them only representing 11 per cent of the population. The countdown starts now to make sure BAME people start to see equality in organ transplantation waiting times in years to come.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News