Bayeux tapestry: a brag, a lament, an embodiment of history's complexity

It is a miracle of cooperation across borders that brings two peoples, two cultures together and reveals they are the same, after all.

I’m not talking about the news this week that France’s president, Emmanuel Macron, has given the go-ahead for the Bayeux tapestry to visit Britain. I am describing the tapestry itself.

Perhaps it is coming to something when we have to turn to the early middle ages for lessons in humanity, compassion and how to be Europeans. The Bayeux tapestry was created in a world of bullying knights, near-universal illiteracy and tiny life expectancies, a remote time when a comet passing in the sky was a sign from God. In 1066 – as every British child is taught – the Normans, a hardy people who had been Vikings before they settled in northern France, invaded England. Their leader, Duke William, seized the crown after killing his Anglo-Saxon rival, Harold Godwinson, at the Battle of Hastings.

Very soon after that fatal battle, a more than 70 metre-long comic strip was created that told the story of the Norman invasion in bold, bright, embroidered woollen images revealing one unexpectedly subtle detail after another to create a moving picture (in every sense) of what war is really like. All great historical events are complex. Modern historians can tell you that and historical novels like War and Peace or Wolf Hall set out to capture it. The Bayeux tapestry shows it. The incredible, mysterious thing about this apparently primitive work made by anonymous craftspeople so long ago is that it shows the truth from multiple points of view, with respect for the losers as well as winners of the most decisive battle in British history.

“It’s a fantastic example of the making of history,” says Simon Schama. The writer, broadcaster and Columbia professor who has done so much to put narrative at the heart of today’s historical thinking and teaching is awed by the storytelling skills of the anonymous embroiderers who filled this panorama with lovely living detail.

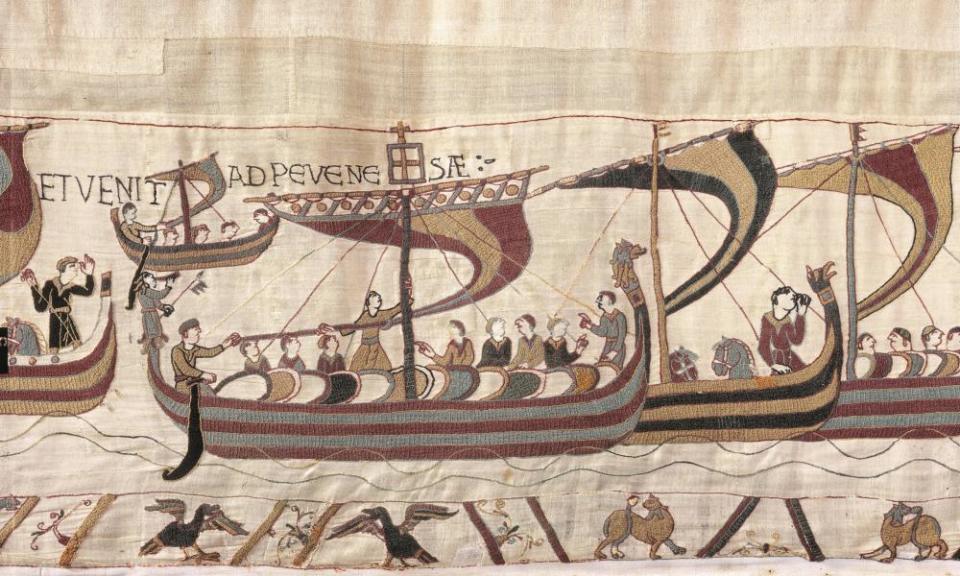

“My favourite bit is where the embroiderers abolish the borders at the point where the armada sails so you have this extension in space, creating the sense of an infinite flotilla. There’s also a couple having it off. And there are these peasants in the border pulling the hauberks [chain-mail armour] off the dead.”

It all starts with a holiday gone wrong. Perhaps the trip the Anglo-Saxon noble Harold takes to Normandy in the early scenes of the tapestry is more business than pleasure, but whatever his plans, they are wrecked. He ends up a “guest” of Duke William, who gets him to swear an oath of loyalty. Harold has to stand placing his hands on two ornate reliquary caskets. William sits on his throne, already the image of a king. He points to the relics in an acutely cinematic, psychologically truthful image of smouldering power.

Already the question hits you – whose side are the artists on? For this is no simple propaganda image. Harold is portrayed just as sensitively as William. This is a moment of strange intimacy. If anything, we’re on Harold’s side.

Schama, like most historians, believes the tapestry was commissioned by Odo, bishop of Bayeux and half-brother to William. After the Norman victory at Hastings, Odo was made Earl of Kent, giving him access to “Europe’s greatest embroiderers – men and women”. The style of Kent’s craftspeople has been detected in the bright wool of the frieze. Chances are it is their work and, in its most subversive moments, their vision.

For ambivalence runs like a subtle thread right through this richly told story. If it only showed the Normans building castles when they landed in England, that would be impressive propaganda. Yet it also shows them burning a house – not such a good look. The Anglo-Saxons meanwhile are portrayed fighting bravely and well. Harold’s death in battle is given tragic pathos. “Really the two armies are indistinguishable,” says Schama. He thinks this even-handed quality underlines “the sense the embroiderers are bound to be English”.

This is where the tapestry becomes not just an image of history but an embodiment of its living complexity. It is both a Norman brag and a Saxon lament. Perhaps we are looking at it with the wrong eyes if we ascribe a fixed point of view – for or against the conquest – to anyone involved in its creation. This is a wise, broadminded, tolerant work of art that sees no need to insult the weak or make gods of the strong.

“It’s so much about Englishness or Britishness and at the same time how that is rooted in Norman-ness,” marvels Schama.

At a time when our relationship with Europe is being remade – or just plain broken – here is a document of how interwoven that relationship really is.

The story behind what happened this week and how Macron came to make such a daring cultural gesture also has an intricate weave. It is not purely a French initiative but started in the British Museum, which is probably where the tapestry will be shown in 2022 so long as scientific tests confirm it can travel.

Under its current director, Hartwig Fischer, as well as his predecessor, Neil MacGregor, this museum has developed an ideal of “cultural diplomacy”, the use of museums and their treasures to open doors between nations and cultures, that has seen it send works to China and loan the Cyrus Cylinder, an ancient Persian treasure, to Iran. Now it is doing cultural diplomacy on Brexit Britain itself by bringing our European story home to us.

In 2013 Michael Lewis, the British museum’s deputy head of Britain, Europe and pre-history, who also happens to be an authority on the Bayeux tapestry, joined a committee to help plan a new gallery in Bayeux for the town’s most precious treasure. As he sat on this committee he got an idea. What would happen to the tapestry while its space was being rebuilt?

“It occurred to me that they will need to take it off display,” Lewis says.

He began talking to his colleagues in Bayeux about the possibility of lending it to Britain. These talks developed until they were taken to civil service levels. Then suddenly the French president stepped in.

So it’s all his idea, not Macron’s?

“I suppose it is really,” he says.

But of course Macron deserves the credit, he insists. The president saw its potential, cut through red tape (of which France has plenty) and has used his authority to make a medieval dream come true.

Fischer agrees. For the British museum’s director, Macron is a visionary.

“He’s extemely aware of what constitutes Europe through history. What are the ideas that have shaped Europe? What is the shared heritage? If you read his speech in Athens last year, he seems to be aware of the role culture plays”.

Macron gave that speech on the ancient Pnyx hill and delivered part of it in Greek. Fischer does not, however, see any analogy between the tapestry and the Parthenon marbles, the treasure of the British Museum whose return Greece has so long demanded. Britain does not claim to own the Bayeux tapestry, after all – he points out.

Is he sure? After speaking to him I see this headline: “The Bayeux tapestry’s English. If the French want it back they’ll have to invade!” It seems a bit premature, before we’ve even got our hands it.

Yet any attempt to twist the tapestry into petty patriotism looks desperate and doomed. This medieval masterpiece is, says Fischer, “about conquest, it’s about exchange. It makes you aware of how national borders come out of a long, long process. If you asked people in the 11th century what their country was, the answer would be very different.”

So there you have it – the Bayeux tapestry is coming to Britain in a remainer plot hatched at the ultra-liberal British Museum.

The year 1066 is where British history starts in a lot of our minds. It’s where the line of monarchs down to today begins. It’s a date we can all latch on to. Thinking about it means thinking about who the British are. If you look at the tapestry with both eyes open the answers to that can easily be seen. It’s true we are an island. The Normans come across in a great fleet of Viking ships. Yet to look at those embroidered ships with their multicoloured sails is to see the richness of the new, the foreign, the different. The Bayeux tapestry is a mix of threads, a carnival of colours. The true flag of Europe.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News