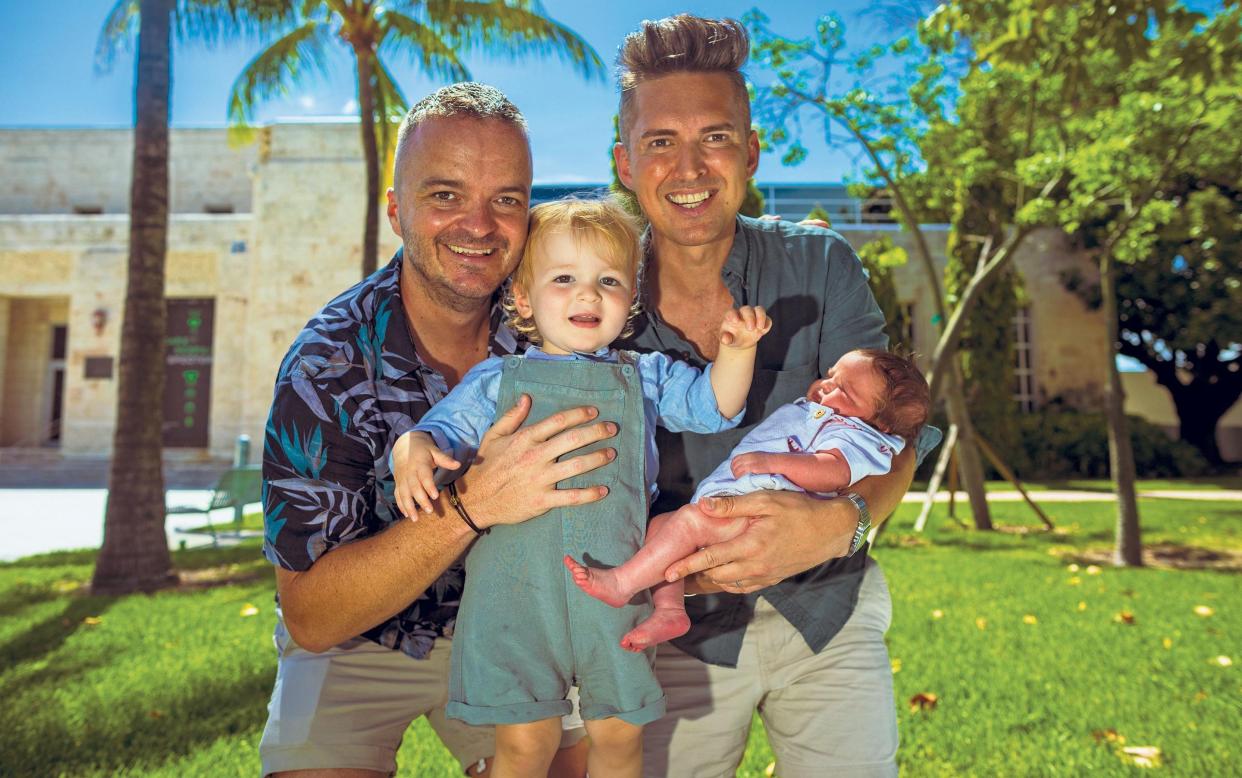

We became fathers to two surrogate babies within 18 months – this is what we learnt

“Complete” feels like the right word to describe my life right now. This Father’s Day is extra special, as it marks the birth of our second son, Aster, who was born three weeks ago. I couldn’t feel happier.

I always knew I wanted to have kids, but ever since my teens I’ve also known myself to be gay. As I got older, friends would ask me: “How are you going to do it? Will you adopt?”

To be honest, I didn’t have a clue. I knew it was going to happen one day, I just didn’t know how. That day came in 2019 during a celebratory dinner with my husband, Ian, in Hong Kong on our sixth wedding anniversary. It didn’t come out of the blue, if I’m honest. We’d been together 11 years and Ian was my first proper boyfriend. I’d mentioned early in our dating life that I wanted to be a parent one day to test the water – truthfully it was a deal breaker for me.

My parents gave me such a happy and stable childhood growing up in the Welsh Valleys, which I didn’t appreciate until I was an adult. It dawned on me I’d like to give the same love and support to a child.

Our friends started having babies so it felt like the right time. I was aware [Olympic diver] Tom Daley and his husband had had a baby via surrogacy in America [in 2018], so I did some Googling, listened to podcasts and phoned some agencies to work out our options.

As you can imagine, navigating the journey from our decision to have a baby – now two – via surrogate wasn’t completely seamless. It was a constant rollercoaster of emotions – highs of pure excitement to the anxious lows and sleepless nights. Although we knew what we were getting ourselves into – the system they have in the US is excellent and slightly more advanced than in the UK.

One of the big differences for us was that in the UK the law states that the surrogate (and their spouse, if they have one) is the legal parent of the baby for up to three months after birth or until consent from the surrogate is approved. This also means that the “carrier” is named as your baby’s parent on their birth certificate and the baby will have her surname during that time until the birth is re-registered. That didn’t make sense to me. Honestly, the whole surrogate journey comes with enough worries.

In the US, once your carrier has reached 25 weeks in the pregnancy, the legal paperwork gets drawn up naming you as intended parents with the carrier’s agreement. So when Wilder and Aster were born, their birth certificates were issued with their names, my name and my husband’s name. That was a huge deciding factor for us. Even though it’s just a bit of paper, it makes our family official.

The surrogate agencies in the US have all been running for longer, so for us this felt like a more tried and tested system. But it never felt like we were in control – how can you be when you are putting a new life into someone else’s hands?

We couldn’t have been luckier when the agency found our carrier, Stephani, who has helped us carry both of our boys. When we met her via Zoom along with her three sons and husband George in February 2020, we clicked. It was such a wonderful moment. It was the start of our new family and the start of a new and very close relationship with a stranger who would be in our lives forever.

You are putting a lot of trust into someone when you have a baby via surrogate, but I knew Stephani would do what was best for our baby and herself. When Covid hit just before the scheduled egg transfer on March 13 2020, Stephani did everything in her power to make sure she was the last transfer in the hospital before the world went into lockdown.

Unfortunately, the Covid travel restrictions meant I watched the birth on Zoom from a hotel room in Tulum, Mexico, en route to Minneapolis. Our baby boy, Wilder Gray, arrived four weeks early in the early hours of November 21 2020. I managed to make it for a cuddle when he was 10 hours old. As I sat in the ward, the tears rolled down my face. That moment, holding my baby boy for the first time, felt so surreal. I felt a tidal wave of emotions – I was finally a dad.

Lockdown turned out to be the best gift for two new parents because we had to stay in the US five months after Wilder was born, which meant we had this very cocoon-like start as a family. I look back on those days with very fond memories. We missed out on the pleasures of a physical pregnancy – like feeling the first kick or watching the bump grow – so this time together was our special bonding time.

It’s going to be different with Aster, as we have to consider Wilder and give him all the love and attention he’s used to. The surrogacy journey itself has been less stressful as we went through the legal paperwork the first time and we already had our embryos. The tricky bit was fitting in the Zoom chats around Wilder’s routine and keeping up-to-date with Stephani’s bump pictures and updates on WhatsApp.

Life has definitely shifted since having kids – we’re not out late on Friday night, or jetting off for weekends away, but that’s okay. We both run our own businesses and work hard, but we’re lucky as we can be flexible. I always make sure I’m back for bedtime. As two dads, we’ve taken a 50/50 approach to parenting from day one.

Now I’ve had children, I realise how much hard work parenting can be, especially for breastfeeding mothers who I have total admiration for. We were determined our roles would be equal. My identity is important to me, I like my work and my social life and I don’t want to lose it. Besides, if I’m happy, then I believe the kids are happy too.

We don’t talk about whose sperm was used for which baby – but we know one was used for Wilder, and another for Aster. We call them “our children” and we’re both their parents.

It was important to me for Wilder to have a brother and best friend. I want them to have a special bond so they can support each other through any kind of difficult moments that might arise in the future, especially as they have same-sex parents. It’s not a huge worry as I know attitudes are different now to when I was bullied at school in the 1990s, but it is in the back of my mind.

We get stopped in the street a lot and people tell us: “You’re so blessed. It’s so beautiful.” And others tell us to enjoy every second and not rush it. We’re trying our best.

‘My two batches are the most perfect things that have ever happened to me’

Journalist William Sitwell on becoming a father again in his 50s

There are some aspects of the universe that I don’t believe will ever be fully explained. I’m thinking about the singularity of black holes, why thistles keep growing on my lawn or how the hell my two smallest children are so chirpy having spent all night awake and coughing.

I, meanwhile, am rendered directionless, dizzy and irritable and in a fog of cantankerous befuddlement, so quite how these very words are dripping onto the page is another mystery to me.

But like teenagers with hangovers or prime ministers grappling with votes of no confidence, I cannot demand nor should I elicit any sympathy. Most fathers become fathers because they freely choose to be. So we congratulate them. When they are in their 20s or 30s we take pleasure in their sprightly energy and the novelty of newborns that sees most of them through the sleepless nights.

But now, in my early 50s, my two are more than ankle-biters: they are great whites, gobbling me up to my torso, dragging me beneath the waves.

It is my own fault of course. I have two older children, aged 17 and 20 – gifted, talented, beautiful creatures – but about five years ago I went into the little shop of life’s stepping-stones and ordered a fresh batch of two.

It means that now, while many of my contemporary dad friends are pondering on who is joining their tennis four or whether to do Corfu or Verdura this August, I am scratching my head wondering how I’m going to pay for school fees in 10 years’ time and whether I’ll get an unbroken, full night’s sleep this side of 2030. While they are weighing up whether to serve English sparkling or champagne before lunch this Sunday, I’m eyeing up 18-month-old Barney in his high-chair, wondering how I’m going to lean across the table and lift him out without slipping a disc.

I remember the time when all the childish paraphernalia for Batch One left the house: the nappy bin, the steriliser, the beakers, the dungarees, the Lego. Never again, I mused, breathing deeply, smugly, satisfactorily. Now it is for other fools to confine their every waking hour to screams, demands, routines and Peppa Pig.

But no. Fate had other ideas. And once again I live in a house of wet wipes, tiny socks and weekends that start at 7pm on a Sunday evening.

I contemplate the selective memory of my brain. Did my older children cough this much and have noses that were 24/7-operating vessels of running snot? Did they, despite having shameful numbers of toys, always choose to fight over a single, bashed-up red tractor or demand “TWO MORE MINUTES” in what is now a cold bath, fracturing my nerves as it is already six minutes past seven? (That’s six minutes past “open fridge door, grasp a bottle – with screw cap for emergency access – and pour a glass of white wine” o’clock.)

While the past may be bleary, technological advances do provide clear blue water between then and now. And they can have mixed blessings. There are the child monitors, for example. Twenty years ago they projected an audio signal around 15ft; today they can be Wi-Fi-enabled. So they don’t just stretch to the pub; you can now watch your children not sleeping in Somerset while you’re on business in Dubai.

The downside of this is that it can turn one a little obsessive. Overseas I am like the plane spotters at Heathrow watching and waiting for the slightest wing wobble. On my phone I witness impending doom as Barney stirs and chucks Peter Rabbit out of his cot.

Baby food has also improved both in form and delivery. Forget spoons and mess and tiny glass jars of revolting sweet potato. A small child can now suck a delectable Ella’s Kitchen organic squash, carrots, apples and prunes puree straight from the pack.

Car seats are no better, however. They’re just heavier, more expensive and need permanent fitting by a qualified engineer. And I can no more work out how to tighten or loosen the straps than I can collapse a pushchair at the steps of an easyJet plane.

But amid the whines and ouches, frenzied switching on and off of lights and heart-attack-inducing costs of childcare, I have rediscovered the unfettered joy of little children and one’s capacity to love.

I will never tire of seeing Barney’s smile in the morning, or my walks with three-and-a-half-year-old Walter as he chatters away, questioning everything while searching for the perfect stick – then, as I relent to his pleads that “my legs aren’t working” and pick him up, getting the tightest, most beautiful hug imaginable. Or, when he’s not discreetly (so he thinks) pushing him over, seeing Walter take Barney’s hand and run across the garden.

For this father, my two batches are actually the most perfect things that have ever happened to me.

‘You still feel that rush of adoration’

Chris George, 51, a healthcare regulator, adopted two children with his partner Helen

I was never one of those people who was desperate to become a dad. My partner Helen and I first met during the upper echelons of childbearing age – we had made our peace with not having a family.

It was only when my dad died, when I was 41, that I started thinking seriously about my life and what I wanted from it. He was such a great dad and had achieved a lot, whereas I’d been living in the same flat and doing the same job for a long time. I felt it was time to move on and do more; we were looking for the next step.

We got a house together and shortly after that time we spotted an advert in the paper from Central Bedfordshire Council inviting people to consider adoption. With a very genuine sort of open mind, we thought we would go along to the information evening to find out a bit more. We’re pretty laid-back about most things, so we approached it with the view that we were going to have a look and think about it. We kept going along to meetings and gradually it began to feel more and more like this was something for us.

We spent a long time with the social worker. It was quite a lengthy assessment, where we talked about our lives and why we wanted to adopt. You often hear people saying the process is really intrusive and far-reaching, but I think we found it pretty straightforward.

I definitely don’t think I was prepared for fatherhood. I sometimes joke that I don’t think I had hung out with a child since I was one. I don’t have any nieces and nephews and while Helen has two nephews, they were teenagers by the time I joined the family. I genuinely had no idea what to expect. Thankfully, Helen was brilliant.

We were offered a lot of profiles of children who were looking for adoptive parents and as soon as we found our daughter, who was 15 months old, we just thought she was gorgeous. On the morning we were set to meet her for the first time, I sat on the sofa at home and thought, “My life is never going to be the same again after today.”

It was overwhelming – but I had no doubts. The foster carer came to her front door with our daughter in her arms. I loved her from the first moment I set eyes on her. Obviously, it’s different from what biological parents experience – Helen wasn’t in a hospital bed giving birth – but you do still feel that rush of love and adoration. I worry that sounds contrived, but it was a monumental moment.

A few years later we went through the whole thing again when we adopted our son when he was 11 months old.

In some cases, adoption can be fraught for people who don’t go into it with the right attitude and expectations. I would say every parent needs more support than they get, but especially adoptive ones. It’s sad to hear about situations when it doesn’t work out. We are fortunate. We’ve always been upfront with both of them about their adoptions – it’s the most ordinary thing in the world for us. Our families have welcomed the children with open arms from day one.

I used to worry about silly things, like being the oldest dad at the school gates, not being prepared enough (I still don’t feel “prepared” for fatherhood, whatever that means: no one tells you that you’re going to have to remember to rinse and drain baked beans before you serve them to your son because he won’t eat them otherwise), but none of that matters really. I can’t imagine not being a dad now – I love it.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News