As the Ben Roberts-Smith case proves, it’s time for Australia to abandon our farcical Anzac myths

A federal court defamation case finding that Ben Roberts-Smith is, on the balance of probabilities, a cold-blooded battlefield murderer has done more than leave Australia’s most decorated living soldier in reputational tatters. It has, perhaps irrevocably, tarnished the carefully curated, revered legend of Anzac and its spurious myth of the white-hatted, egalitarian, hard-but-fair battlefield conduct of the celebrated Aussie digger.

The problem with myths, of course, is that they stand to be demythologised by unsavoury fact. It gets in the way.

Myth, of course, also relies on belief. Often suspended. Belief is the bedrock of religious or other faiths. Faiths like Anzac.

For Anzac is nothing if not Australia’s secular religion, one cherished and celebrated as core to our national identity by generations of political leaders, sporting identities and cultural influencers – historians, journalists, film-makers, authors and visual artists.

The finding against Roberts-Smith in his defamation case loss on Thursday lays bare, yet again, the flipside to the Anzac legend and brings into stark relief the perils of tying national celebration – and adulation – to the battlefield.

For well over a century Australian military personnel have been committing serious crimes on foreign battlefields. The 2020 Brereton report into alleged war crimes by Australian special forces in Afghanistan carefully contextualised its findings against contemporary soldiers on foreign operations. It highlighted that from Australia’s colonial adventurism in the Boer war and through the first world war, into battles in Europe and the Pacific in world war two and into Vietnam and beyond, Australian soldiers had been involved in many unlawful killings.

It’s not something you’ll learn about when you look at the dioramas and other displays chronicling Australia’s martial history at our national secular shrine, the Australian War Memorial. You’ll learn about enemy atrocities, to be sure. But the Australian combatant is largely lionised.

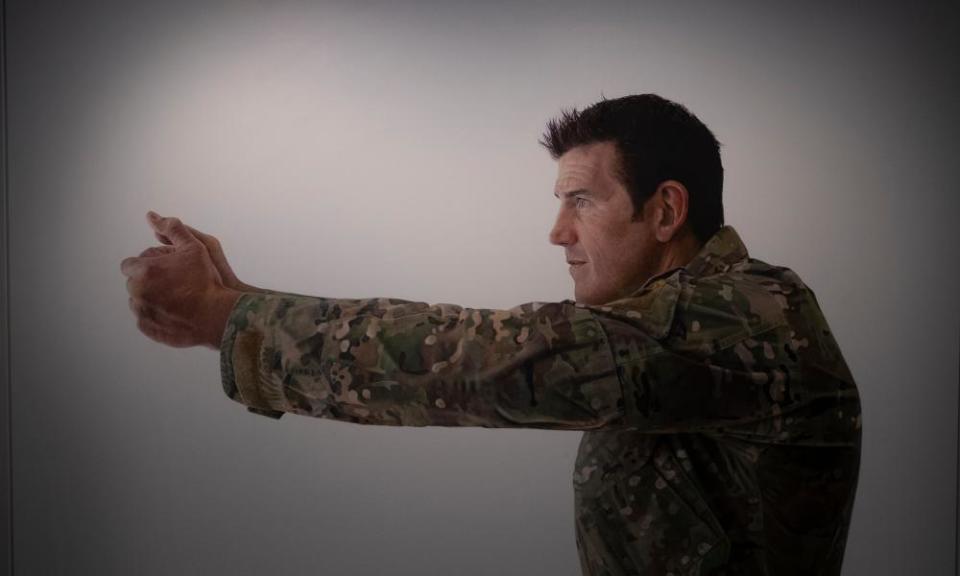

And none more so, of course, than the disgraced Roberts-Smith, two portraits of whom hang in pride of place. One measures an immodest, imposing 1.6m by 2.2m and features him in a combat pose as if about to fire a handgun. Pistol grip, it is titled. Michael Zavros painted a hero who, the artist said, when asked to adopt a fighting stance, “went to this whole other mode. He was suddenly this other creature and I immediately saw all these other things. It showed me what he is capable of … it was just there in this flash.”

Pistol grip asks: do we get the heroes we deserve or those we create?

The governing council of the memorial – many leading politicians, former prime ministers and party leaders among them – have been waiting anxiously for Justice Anthony Besanko’s judgment in the Roberts-Smith defamation case. The memorial has, to understate it, had significant investment in Roberts-Smith’s reputational battle.

The former war memorial director, one-time Liberal leader and defence minister Brendan Nelson, the one-time prime minister and council board member Tony Abbott and Kerry Stokes – Roberts-Smith’s employer, the bankroller of his defamation action, former memorial council chair and a generous donor towards AWM exhibitions – have all assiduously, some would say recklessly, supported Roberts-Smith to the hilt.

Abbott said people ought be cautious not to “judge soldiers operating in the heat of combat under the fog of war by the same standards that we would judge civilians”.

Well, the federal court doesn’t discriminate, as it happens.

Related: Ben Roberts-Smith: the explosive allegations of war crimes at the heart of defamation case

Nelson said some journalists’ allegations against Roberts-Smith were an attempt to “tear down our heroes”. “But as far as I am concerned, unless there have been the most egregious breaches of laws of armed conflict, we should leave it all alone,” he said.

The problem is it’s all been left alone far too long. Good history – like good journalism and justice – has as its bedrock fact.

It’s time we got past our national reliance on belief when it comes to Anzac’s white-hatted digger, its farcical myth and its long tail into Australia’s contemporary defence force.

Ben Roberts-Smith seems destined to play a critical part in such a national awakening.

• Paul Daley is a Guardian Australia columnist

• Support and counselling for Australian veterans and their families is available 24 hours a day from Open Arms on 1800 011 046 or openarms.gov.au and Safe Zone Support on 1800 142 072

Yahoo News

Yahoo News