Betty Davis projected her own liberation – and freed up generations in her wake

Loved by artists from Prince to Butthole Surfers, Davis created a fearlessly sexual, futurist sound that sowed the seed of rebellion

• Betty Davis, raw funk pioneer, dies at 77

In 1974, a year before the release of Nasty Gal, the third studio album by funk and fashion trailblazer Betty Davis, the New York Times predicted that her radical, raunchy music would eventually be appreciated, if only people would let themselves catch up with her: “Miss Davis is trying to tell us something real and basic about our irrational needs, and western civilisation puts its highest premiums on conformity and rationality and rarely recognises the Bessies or the Bettys until they’re gone.”

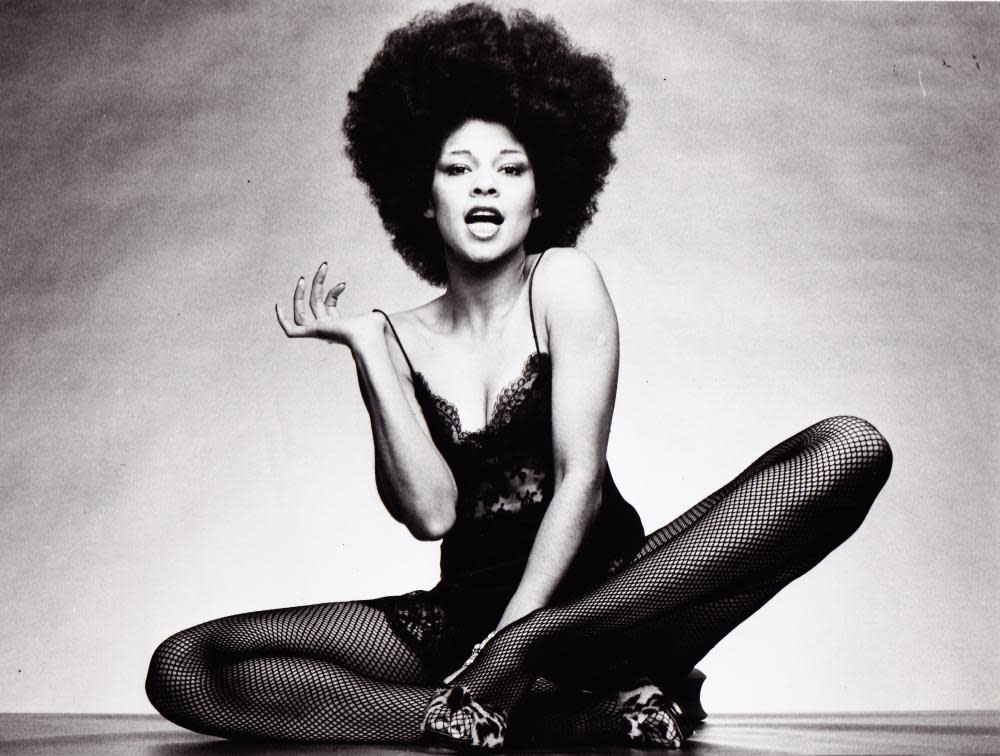

Rather than conform, Davis, who has died aged 77, let the landmark discography she recorded in the 1970s speak for her, along with the sultry, futurist stage persona she created in a powerfully tall afro, cosmic leotards, sequinned hot pants and silver thigh-high boots. “I made three albums of hard funk,” Davis said in the 2017 documentary They Say I’m Different. “I put everything there.” And then, for decades, she vanished from the public eye.

That those albums still sound revolutionary in 2022 says as much about the world as it does about Betty Davis, who will be remembered for the doors she opened and for the incandescent mark she made. Davis was the geist of her zeit, a fashion design student and model who worked for Halston, Norma Kamali and Betsey Johnson. She wrote songs for the Commodores that got them signed to Motown; the Chambers Brothers perform a slinky version of her Uptown (to Harlem) at the Harlem Cultural festival of 1969, finally immortalised in the Questlove-directed, Oscar-nominated Summer of Soul. She electrified Miles Davis, with whom she had a brief and reportedly stormy marriage, during which she turned him on to the psychedelic and funk music of her friends Sly and the Family Stone and Jimi Hendrix, pointing the way toward Bitches Brew. She also helped Davis ditch his formal Italian suits in favour of scarves and platform shoes. Meanwhile, Marc Bolan encouraged Betty to record her own music. She recorded with the Pointer Sisters and Sylvester as well as members of the Family Stone and also her own actual family – a band of cousins and friends from North Carolina called Funk House.

In a 1970s radio interview, asked to characterise her music, Davis let her answer slowly crackle. “Mmm,” she said. “I’d just say it was raw.” You could try to dredge up some metaphor about that rawness, the feral howl of her voice, how its gritty undertones might have absorbed the smoke of the cigarette factories in her hometowns of Durham and Reidsville, North Carolina, or the steel mills of her teenage years, after her family moved to Pittsburgh. Born Betty Grey Mabry in 1944, Davis was raised on her grandma’s BB King, Elmore James and Jimmy Reed records. Decades later, Davis would call herself a “projector”, not a singer. What Davis projected was liberation. Once in the early 1960s, Davis showed up at Park Place AME Church in a fur coat, miniskirt and fishnet tights. In a phone call on the day of Davis’s passing, Connie Portis, her friend of 65 years, recalled her teenage friend in a local talent show, performing an original Davis had titled Get Ready for Betty. “That was the handwriting on the wall.”

Years later, when Portis saw Davis perform on a bill with “either War or Kool and the Gang” in DC, she was shocked by her wildness. But backstage, Portis says, “She was the same Betty. She never drank, never smoked, never did drugs.” Betty autographed publicity photos of herself in sky-high boots and hot pants and mailed them back home to North Carolina, personalising them “to Grandma”.

Davis was a projector, too, of unabashed individuality and sexuality in a way that scared her male peers. “I even turned your head around now,” Davis sang in Nasty Gal. More handwriting on the wall, a lipstick scrawl. “You said I love you every way but your way / And my way was too dirty for you now.”

In the 1970s, her songs were frequently banned from the radio. Even the NAACP urged a boycott of her work on the grounds that it perpetuated negative stereotypes. For a woman, and especially a Black woman, in the 1970s to sing about desire and sex so openly and unabashedly was outside the realm of the civil rights movement. Although Island Records failed to renew her contract, she had already paved the way for others.

Related: Cult heroes: Betty Davis – blistering funk pioneer and fearless female artist

Remove Betty Davis from the strand and you can picture the fallen pearls scattering around the room: Janelle Monáe, Outkast, Cardi B. Miles Davis said she was Madonna before Madonna, Prince before Prince (who played her song If I’m in Luck I Might Get Picked Up as inspiration for his own band). In the wake of Davis’s death, a quote circulated from a conversation about Davis between musicians Erykah Badu and Joi. As Badu concluded: “We just grains of sand in her Bettyness.” Her Bettyness extends far and wide: King Coffey of influential Texan punk band the Butthole Surfers recalled his adulation for his favourite Betty Davis song, Game Is My Middle Name, calling it “certainly the toughest riff of 1973”.

Her influence continued after she retreated from music: over the last 15 years, Light in the Attic has unveiled previously unreleased Davis gems, including another come-on, I Will Take That Ride, in which Davis sang: “Is it true that you want to hi-ho my silver?” (The label will reissue Davis’ final studio album, Crashin’ from Passion, later this year.)

After breaking with Island, and following the death of her father, with whom she had an especially close bond, Davis spent a year recording and performing in Japan, before returning to Pittsburgh. I believe Davis will be remembered for this, too – of extending the bravery she exhibited on stage to her backstage self, to work to heal herself and to protect the parts of her self and her life that were her own. “She was very private, but she never stopped writing,” Portis says. “Betty opened up the way for others to be brazen and brash and to say what they wanted to say.” We still have some catching up to do.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News