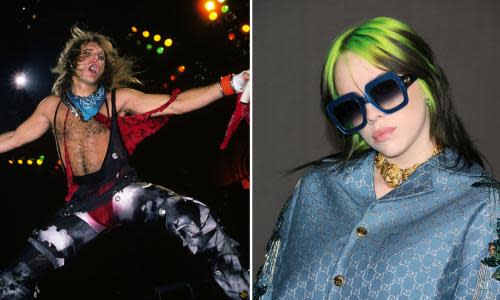

Billie Eilish v Van Halen: what makes older music click with young people

At this point, the arguments about Billie Eilish never having heard of Van Halen – as she admitted to US talk show host Jimmy Fallon this week – have been played out: a bare handful saying the band are titans of rock and everyone should know their mighty works! Then a much larger number saying they are old men who were huge decades before Eilish was even born! What’s more interesting, perhaps, is why she (and most other 17-year-olds) hasn’t heard of them, whereas she had heard of Madonna and Cyndi Lauper, and every teenager I know (I’ve got a 16-year-old and a 19-year-old) has some selection of long-departed heritage acts that they adore.

Often knowledge of older music comes through parents (my kids, I’m afraid, do know who Van Halen are; my son is irritated that he doesn’t know any Oasis songs because I’ve never played them, but all his friends do), but that has always been the way. Other music survives because it continues to talk across generations, and not necessarily because of its greatness – more because it is still part of a wider cultural narrative. And, looking at the sphere in which Van Halen exist – rock music – you can see that most clearly, perhaps when you look at the bands who can fill stadiums with crowds in which there are lots of teenagers and who still get booked to headline festivals for those same teenagers: Foo Fighters, the double bill of Green Day and Weezer that is touring next year; Red Hot Chili Peppers, Blink-182 (when they’re all talking to each other), and in the way it’s not just the old folks who turn out to see Liam Gallagher or Noel Gallagher or U2. I’ve never seen Pearl Jam, so I don’t know whether they can still bring out a younger audience, but I wouldn’t bet against it.

What’s interesting is that, with rock music at least, the bands who have a place in the consciousness of a younger audience tend to be those who postdate the rise of “alternative” music, or those who, like U2 and the Red Hot Chili Peppers, had their roots in the alternative music of an earlier generation.

One might expect that streaming culture, by making all music available to everyone, would have revived lots of bands who were hugely popular in the past. But it hasn’t happened that way because you still need to know that Van Halen existed in the first place, and the culture is not filled with people talking about Van Halen (other than me and some people in America, so far as I can tell). Thinking out loud, it seems now as though the rock music that reaches a younger audience is the stuff that springs from three strands: grunge and the alternative rock explosion in the US in the early 1990s (for all that they were never a grunge band, this was the point that the Chili Peppers exploded); the pop punk and emo boom of a few years later; and Britpop (the latter’s effects still rumbling on in the form of lads-of-the-people bands such as the Courteeners, Catfish and the Bottlemen, and perhaps even Gerry Cinnamon).

The three music revolutions of the 90s created new norms. Grunge reshaped the way rock was viewed not just by critics, but by the wider public

How we in the UK laughed when a US documentary was released entitled 1991: The Year Punk Broke; in retrospect it looks perfectly named. Whereas the original punk movement had deep and profound influence, it didn’t succeed in shifting the rock mainstream to any great extent. It affected mainstream pop much more than it did rock – notably in the new romantic and new pop movements that followed. Those three revolutions in the 90s, though, really did. They created new norms. The notion that grunge killed hair metal is, I suspect an oversimplification (those bands’ time was up anyway; they had already had the best part of a decade; they were tired and drugged-out and would have been replaced by something else had grunge not come along). But grunge reshaped the way rock was viewed not just by critics, but by the wider public.

That’s not to say the older generation lost everything. As Def Leppard’s Joe Elliott said to me of his band in the mid-90s: “We were doing two sold-out nights everywhere rather than three. We were doing 24,000 instead of 36,000 people. But it was still 24,000 people.” That’s still the case with lots of those bands – big, but not attracting anyone new: recently, one festival booker was telling me about negotiations with a big rock band of the pre-alternative era, a band that Billie Eilish probably would have heard of. They concluded that while they knew the name recognition would be fine, they weren’t convinced that enough people even at a huge and popular festival in Europe would know enough of their songs to justify giving them the high slot that the size of their own fanbase would seem to justify.

Related: Sign up for the Sleeve Notes email: music news, bold reviews and unexpected extras

But because mainstream rock music has rather stultified since the 90s, nothing has come along to clear away the acts who became stars in that decade. There have been individual bands – notably the Arctic Monkeys, Kings of Leon, the Strokes and the White Stripes, all of whom also sprang from alternative music – but no movements that really gathered force beyond their particular moments in time. And so Foo Fighters et al continue to rule.

So to go back to Billie Eilish and Van Halen. It’s not because Van Halen are old that she hasn’t heard of them. It’s that Van Halen – for all that I sincerely believe them to be the second most important rock band of all time, after the Beatles – aren’t even in the lineage of bands of whom you might reasonably expect a teenager to have heard of, let alone listened to. Fame in one lifetime does not automatically translate to fame in another, and the way influence spreads is not subject to the normal rules of progression. It’s more like a virus that jumps and mutates in baffling ways – witness the sudden re-emergence of Fleetwood Mac into the sound of young artists a few years back, or Fiona Apple being called “the godmother of 2019” for her influence on Lana Del Rey, Maggie Rogers, King Princess and, yes, Eilish. Maybe Van Halen will be a carrier for that virus one day. But not now.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News