Boris Johnson says tax cuts bring in revenue. But we now know that’s a myth

This time next week the tumbril calls for Theresa May, that removal van freighted with symbolism. Boris Johnson will kiss hands the next day, not elected by us, not with our consent, no “one nation” unifier but leader of a dysfunctional, disunited kingdom. He will get the usual goodwill poll bounce: May and Gordon Brown had theirs. Skipping spring-heeled across the Downing Street threshold, full of vacuous optimism and “let the sun shine in” self-intoxication, he may bring smiles to the faces of admirers.

His honeymoon will barely pass a hundred days before he hits the Brexit wall

His honeymoon will barely pass 100 days before he hits the Brexit wall. A retread of May’s deal will be greeted as “betrayal” by Nigel Farage and the European Research Group. A no-deal crash-out will be a cataclysm. In an election, Johnson risks beating all records for the shortest term as prime minister. But other storm clouds are gathering, darker by the day. Read the financial figures, look at the forecasts, and the rumble is everywhere of an approaching crash, recession or severe downturn. Barometer readings show the global slowdown accelerating fastest towards Brexit-stricken Britain. Johnson may gaily dismiss it as gloomageddon, but whistling in the dark won’t chase it away.

The Resolution Foundation warns we face the highest recession risk since 2007. Mark Carney, governor of the Bank of England, this month warned of threatening recession. The pound has fallen further since the referendum than when the UK fell out of the exchange rate mechanism in 1992, yet devaluation has done nothing for exports, the trade deficit soaring again this year. Construction and manufacturing figures are dropping like a stone and people have stopped shopping, with sales down three months in a row. Household debt is the highest recorded – an average of £15,000 on credit cards, not including mortgages. The employment agency Reed reports new job growth falling fast. Accountant EY reports “crisis levels” of profit warnings by listed companies, not seen since 2008.

This comes after a disastrously slow-growth decade, with wages still not back to pre-crash levels, a stagnation unknown since Napoleonic times. Resolution warns of few weapons left in the armoury, with interest rates at record lows and national debt up by 72% since 2010.

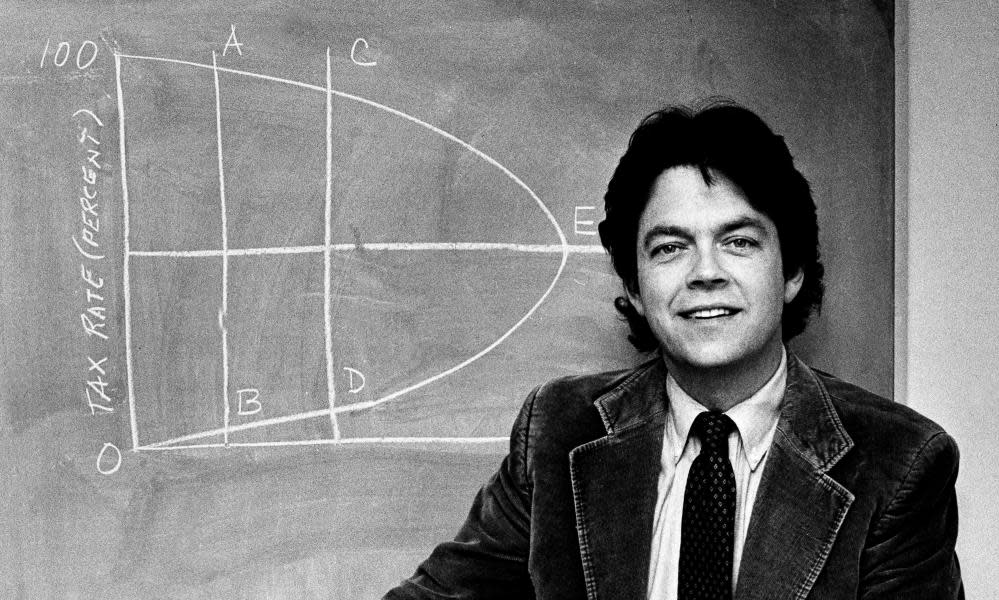

What would Johnson and his cabinet do? The auguries are ominous. Their only economic policy has been tax cuts, competing to shrink the state’s revenue. Dominic Raab wants 5p off income tax and a top rate of 35%. Sajid Javid would also abolish the 45% rate. Jeremy Hunt would cut corporation tax to 12.5%. Michael Gove would replace VAT with a lower sales tax. Johnson proposes spending £9bn on raising the threshold for top taxpayers, and cutting stamp duty on property, with national insurance cuts as an afterthought. All say cutting taxes will bring in more revenue. Rattling beneath their words is their evidence-free faith that tax cuts pay for themselves, the Tory magic money tree: “It’s something called the Laffer curve!” Johnson blasts out time and again in hustings when asked how he could afford to do it.

Related: From Trump to Boris Johnson, we’re moving from post-truth to post-shame | Alastair Campbell

The Laffer curve is a regular in his columns, though his latest pretentiousness name-checks another tax-cutting guru – an obscure 14th-century Islamic scholar, Ibn Khaldun. The theory is that a tipping point comes where tax cuts incentivise entrepreneurial drive, encouraging overtime and higher earnings, yielding more tax. This theory has been exploded time and again, but it’s far too convenient a creed for conservative politicians and the rich to let it die.

Last month 78-year-old Arthur Laffer, who came up with this nonsense, was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom, hung round his neck by Donald Trump, who was flattered by Laffer’s book Trumponics, which praised his tax cuts for the wealthy. Laffer advised Ronald Reagan, who cut top tax from 70% to 28% and caused the highest national debt since the war. Unsurprisingly, Trump’s debts are rising fast too, up $739bn so far this year, and with nothing to show for it (debt increases are reasonable, if used for national investment).

There was a real-life experiment in Kansas in 2012, when the governor summoned Laffer, who promised massive revenue and job gains. Tax was cut by a third, but revenue dropped 10% in a year, schools were closed, Medicaid slashed, few jobs were created and growth fell below national levels. It had to be abandoned. Laffer says it didn’t work because “it didn’t go far enough”, like the far left’s excuse for communism’s failures.

The consensus of research finds the Laffer curve does kick in – but not until tax rates surpass 75%. Until then, higher taxes produce higher revenues. Research by Emmanuel Saez and Thomas Piketty shows countries that cut their top rates did not have higher growth: instead cuts can stimulate what economists call worthless rent-seeking rather than enterprise.

Does lower top tax mean less evasion by the rich? Not according to a tax official I interviewed who had been at the Inland Revenue in 1988 when Nigel Lawson cut the top rate from 60% to 40%. He said they expected their workload to fall as the rich would abandon complex avoidance schemes: it didn’t happen. Instead the “tax is theft, greed is good” political culture of those times spurred the wealthy on.

But Boris Johnson chooses to believe in Laffer, as do Javid, an Ayn Rand admirer, and Raab, both bidding to be his chancellor. So does Liz Truss, backed for the post this week by Philip Hammond, who says admiringly: “She’s even meaner than me. She won’t let people spend irresponsibly. She’s really tough.” Whoever Johnson appoints, don’t expect Laffer to disappear from the lexicon of bad reasons why the rich should pay less, while depleting the exchequer. This cadre are all bred of the same small-state, tax-cutting genes. What happens when this anti-tax dogma meets the harsh reality of Brexit and recession won’t be a pretty sight.

• Polly Toynbee is a Guardian columnist

Yahoo News

Yahoo News