Boris Johnson: The world would be a better place if all girls went to school

I am always dubious about so-called silver bullets that allegedly solve a host of problems. “Life can’t be that simple,” I think. “Surely there must be a catch?”

But there is one step that would improve countless lives — and make the world an infinitely better place — if only every government summoned the will to make it happen. Let me spell out what needs to be done: make sure that all girls go to school.

Today, the appalling truth is that about 61 million girls between the ages of five and 14 are deprived of an education across the world. In countries such as Nigeria, Afghanistan and Pakistan there are millions of girls who never get the chance to enter a classroom.

In some places, schools just do not exist; in others, prejudice, violence and poverty deny girls the education that is their right. Whatever the reason, this failure to allow every girl to attend school is holding back entire societies.

If political leaders would wake up to the benefits — and the essential justice — of educating the daughters of their countries just as surely as they educate their sons, then everyone would be immeasurably better off.

Do you want to boost economic growth? Or reduce population pressures? What about reducing infant mortality and improving child nutrition? In every case the single most effective remedy is to give all girls the opportunity to attend school. That is not a matter of opinion: it is proven fact.

I will let the conclusions of a United Nations study speak for themselves. If all women went to secondary school, says the UN report, then infant mortality would be cut in half and three million young lives saved every year. About 12 million children would not have their growth stunted by malnutrition.

The tragedy of child marriages would also become less common. The UN calculates that if every girl went to secondary school the prevalence of child marriage would fall by two- thirds.

And the pressures exerted by rising populations would be brought under control. Women in sub-Saharan Africa who never attend school give birth an average of 6.7 times. For those with secondary education the figure plummets to 3.9.

The conclusion is crystal-clear: allowing girls into the classroom is both profoundly right in itself and the single most powerful spur to development and progress. It’s also the surest way of achieving the broader emancipation of women that we would all like to see. When girls are deprived of an education they become vulnerable and powerless —easy prey for those who would force them into work or early marriage.

Fortunately the situation is slowly improving in many countries, not least because of the great work being done by Priti Patel and the Department for International Development.

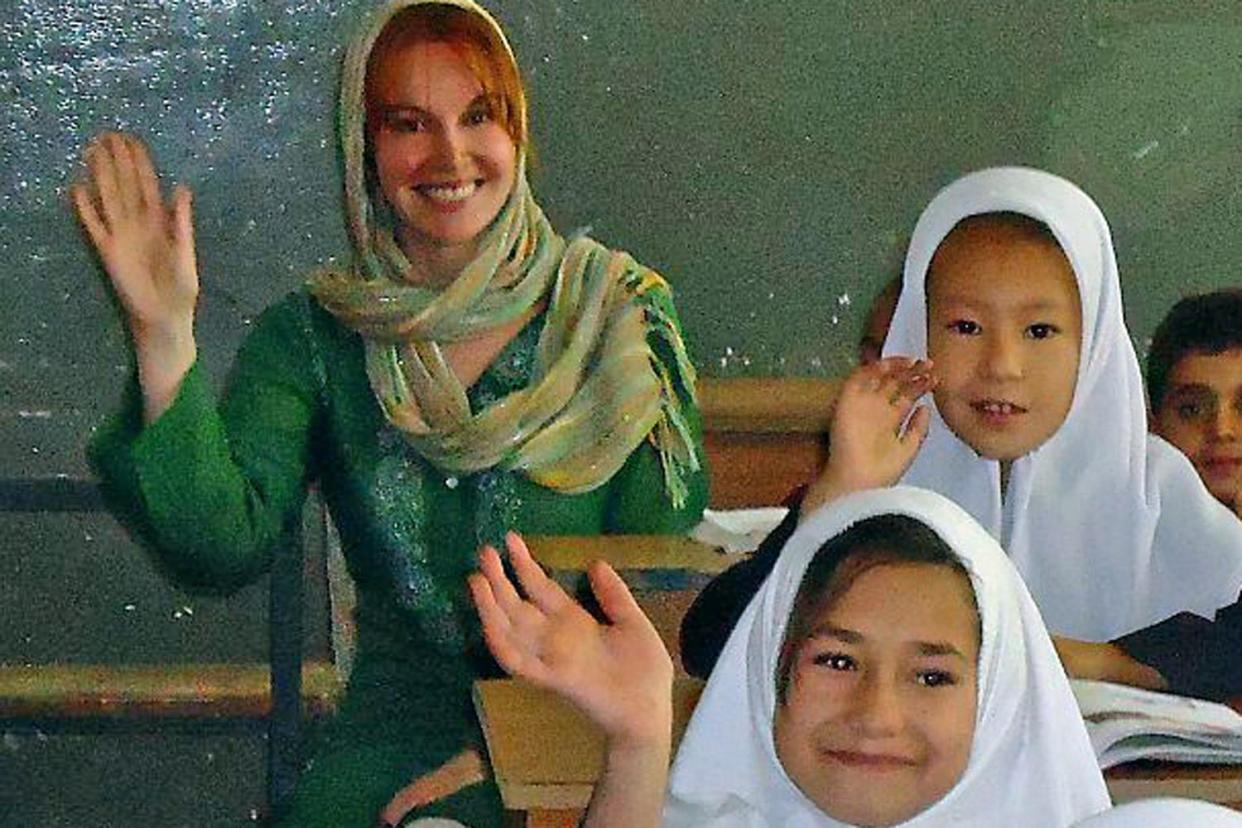

Last year I saw for myself how the DfID is helping six million girls to attend school in Punjab province in Pakistan. And I visited Kabul University in Afghanistan, where I was fortunate enough to see Macbeth performed by a partly female cast. This was a scene that would have been inconceivable when the Taliban was tormenting Kabul barely two decades ago. There before me were young Afghan women, free to perform Shakespeare in the Dari tongue.

Before 2001 the number of girls attending school in Taliban-ruled Afghanistan was close to zero. Female education was actually banned. Women teachers were sacked and, since they comprised the majority of the profession, the result was the virtual collapse of the education system.

Today, by contrast, there are at least two million girls in the classrooms of Afghanistan — thanks in large measure to the British forces that served in the country. If you want to point out one crowning achievement of the toil and valour of our servicemen and women, look no further than the Afghan girls who now have the chance to go to school.

Across the world, DfID provides the money and the programmes to help girls into the classroom. And we should have no illusions that plenty of other factors, quite apart from the denial of education, hold women back. One of my priorities as Foreign Secretary is to use every relevant platform to advance the cause of female education.

Next month I will visit the UN in New York during the second week of the Commission on the Status of Women, the principal global gathering dedicated to fostering gender equality.

Later this year I will host a conference on the future of Somalia. I’ll take the opportunity to highlight how the lack of female education is holding back progress in that country.

I want the Foreign Office to play its part and reflect on how we can take forward the goal of gender equality within our own organisation.

Today I’m hosting a reception at the Foreign Office where I will announce that I’ve chosen one our most senior diplomats, Joanna Roper, to be special envoy for gender equality.

One day I hope it will no longer be a rarity for Afghan women to study at university — and perform Shakespeare if they wish. I look forward to the day when every girl has the chance to go to school.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News