Brazil's right on the rise as anger grows over scandal and corruption

Fernando Holiday is one of the few openly gay, black politicians in Brazil, but before he won a single vote, he first reached national fame in 2015 with a string of viral videos in which he attacked Brazil’s affirmative action system for black, indigenous and poor people.

“We blacks and poor can win in life on merit,” he said in one Facebook video. “I don’t play the victim.”

That year, Holiday became a leading figure in the Free Brazil Movement – a rightwing pressure group instrumental in the mass street demonstrations against the corruption unveiled by Operation Car Wash, an investigation into a multi-billion dollar graft scheme at state-run oil company Petrobras.

Protesters demanded the impeachment of then-president Dilma Rousseff, who was eventually ousted in August 2016 for breaking budget laws. Two months later, Holiday was elected to the São Paulo city council for the conservative Democrats party, one of eight municipal representatives linked to the Free Brazil Movement.

Groups like these are now forcing a sea change in the politics of a country run for 13 years by the leftwing Workers’ party founded by Rousseff’s predecessor, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva.

“The swing voters moved to the right,” said Marcus Melo, a professor of political science at the Federal University of Pernambuco.

Brazil’s economy is struggling to escape recession. There are 14 million people unemployed. Violent crime is rising, while the graft scandals that tainted Rousseff’s party have since entangled the administration of her successor, Michel Temer. And disillusioned Brazilians are increasingly looking to free-market liberals, evangelical Christians, and populist, rightwing populists.

In the same municipal elections that propelled Holiday to the council chamber, João Doria, a conservative businessman and former presenter of Brazil’s version of The Apprentice, won an unprecedented first-round victory as mayor of São Paulo, South America’s biggest city, and Marcelo Crivella, a fundamentalist, evangelical bishop, was elected mayor of Rio de Janeiro.

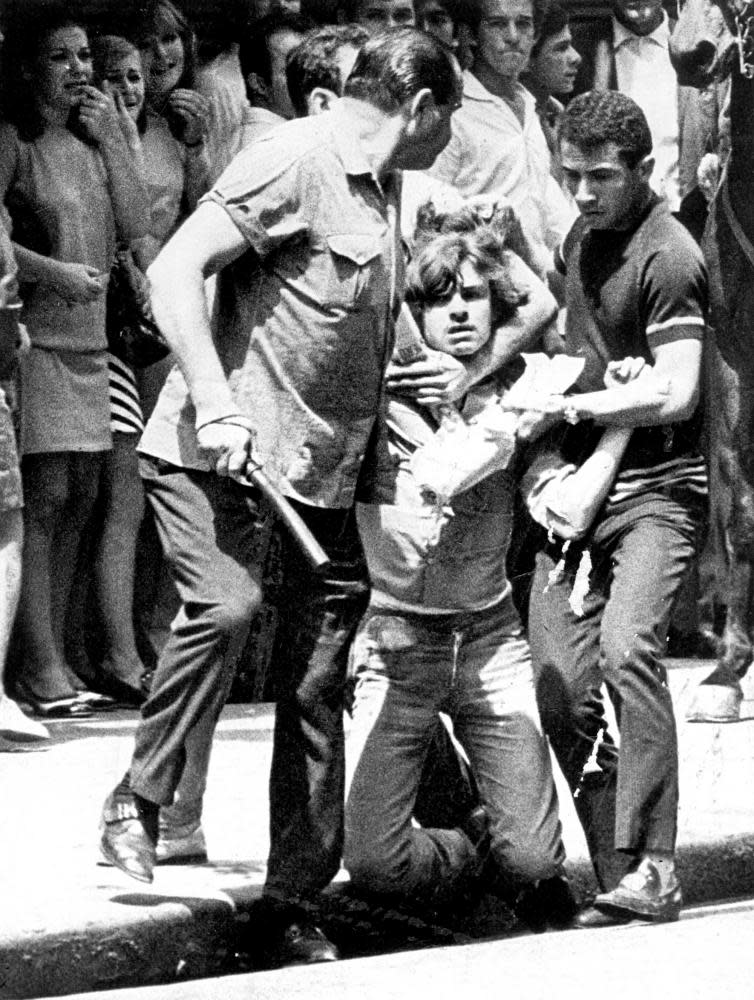

On the national stage, Jair Bolsonaro, a former army captain and federal deputy, is currently running second in some polls for the 2018 presidential elections. He has an aggressively rightwing, anti-crime platform, espouses homophobic views, and has lauded the military dictatorship that ran Brazil from 1964 to 1985, executed hundreds of its opponents and brutally tortured thousands more, including Rousseff, a former Marxist guerilla.

Bolsonaro, who promises to appoint generals to his cabinet if elected, is greeted by cheering crowds at airports and rallies who chant his name and boast that he has never been linked to any corruption allegations – unlike many of his fellow lawmakers.

His supporters say they felt legitimised by the pro-impeachment protests.

Before then “it was inadmissible for you to position yourself as rightwing in Brazil – it was basically a swear word,” said Douglas Garcia, 23, one of the organisers of São Paulo Right, a pro-Bolsonaro group with 185,000 followers on its Facebook page.

The Free Brazil Movement began from an “anxiety to create a simple language and spread and transform economic and political liberalism into a relevant political force in Brazil,” said Kim Kataguiri, 21, another of its young leaders, who plans to stand for Congress in next year’s elections.

He said some Free Brazil Movement coordinators had received training by Students for Liberty, a free-market advocacy network that is part of the Atlas Network, an American non-profit organisation that spreads free market ideals. Students for Liberty and the Atlas Network have received funding from Charles Koch, who with his brother David, controls Koch Industries – the US energy, fossil fuels and petrochemicals behemoth.

Fabio Ostermann, an independent political scientist based in Porto Alegre in the south of Brazil, helped found the Free Brazil Movement and was also a member of the Brazilian branch of Students for Liberty. He was a Koch summer fellow at the Institute for Humane Studies in Virginia for three months.

“They give basic training, an introduction on how to organise a thinktank, how to publicise liberal ideas,” he said. “It was a first-world education that gave me a analytic capability beyond the Brazilian reality.”

Like Charles Koch, Ostermann downplays the risks of climate change. He has since left the Free Brazil Movement because, he said, they support the Temer government, which he regards as corrupt. Yet he agrees with them on one key point: neither support the return of a military dictatorship.

But others on the Brazilian right do. And every Monday evening, a group of about 40 meet in an ornate, chandelier-lit salon at São Paulo’s private Nacional Club.

“[When] you have thieves in the state, you have to call the police. Who are the people’s police? It’s the army,” said Antônio Paiva, 68, a lawyer and rural producer, before the meeting began. He said a junta of two civilians and a military officer should take over Brazil for up to two years and gradually reintroduce democracy, starting with municipal elections.

Afterwards, as participants ate cake to celebrate Paiva’s birthday, Edna Leite, 61, a public education official, said the 1979 amnesty that preceded Brazil’s return to democracy had allowed too many leftist leaders back into society – like Rousseff.

“You can’t recuperate these people for society,” she said. “Eliminate them.”

Those openly calling for a return to military dictatorship are a minority, but they appear to be growing.

Support for democracy fell from 54% in 2015 to 32% in 2016, according to Latin Barometer, an annual, continent-wide survey. And support for the return to military dictatorship is increasingly being expressed in Brazilian society, said Enio Mainardi, 82, a retired advertising mogul whose Facebook page, which he uses to disseminate rightwing views and berate the Brazilian left, has nearly 20,000 followers.

He opposed Brazil’s military dictatorship as a young man, but is now changing his mind, he said.

“I had no notion, it wasn’t clear, that the military regime was right,” he said.

Mainardi’s son Diogo is one of the founders of The Antagonist, an influential rightwing news site that supports Operation Car Wash and Sergio Moro and attacks the Workers’ party.

Supporters of Lula and Rousseff say that the rich loathe the Workers’ Party because it did more to help the Brazilian poor than anyone else, but Mainardi said the party was corrupted by power.

“If you read what reasonable people say on Facebook, you will see the hate,” Mainardi said. His retired wife Teresa Mainardi, 64, said she supported military intervention to control Brazil’s vast population.

Both would vote for Jair Bolsonaro in the 2018 election over Lula, who currently leads polls. But earlier this month Lula was sentenced to nearly 10 years in prison for corruption and money-laundering which could render him ineligible.

None of the rightwing candidates are likely to be good news for the Amazon, where deforestation rose 29% last year.

In an April interview with Brazil’s Estado de S.Paulo newspaper, Bolsonaro said Brazil should clear more forest land to produce food for a growing world population.

Environmentalists, he said, “hope that I don’t become president.”

Yahoo News

Yahoo News