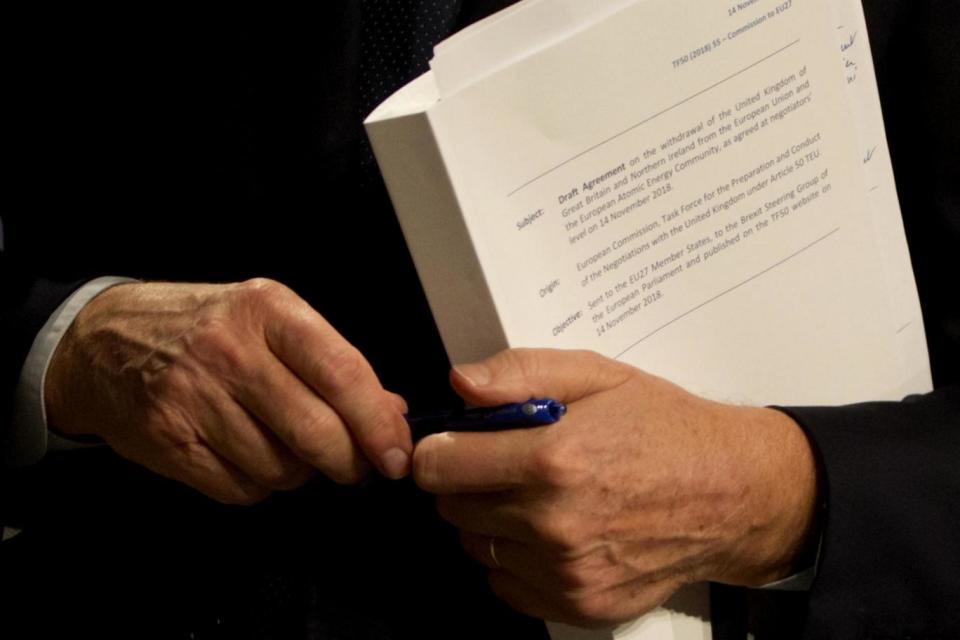

What is the Brexit deal? Theresa May's controversial withdrawal agreement with EU explained

Theresa May has survived a vote of confidence in her leadership.

The Prime Minister was under huge pressure to step down following widespread opposition to her Brexit deal, particularly over the proposals on the Irish border backstop.

Mrs May blamed the Irish border issue for delaying the Parliament vote on the deal.

Tensions within the party are rising following Mrs May's crucial meeting with EU president Jean-Claude Juncker, with the Tory leader concluding that the agreement was "the best deal available, indeed it is the only deal available."

Here, the Standard outlines the crucial key points made in the draft proposal:

The Irish border

The most contentious issue is the Northern Irish 'backstop', which is essentially an insurance policy to avoid a return to border checks between Britain and EU-member Ireland that could threaten the 1998 peace accord, which ended 30 years of violence.

The draft deal envisages a July 2020 decision on what would have to be done to make sure the border stays open after the post-Brexit transition runs its course. That’s if a new trade deal is not in place by then.

Either Britain would need to extend the transition period once beyond December 2020, or go into a customs arrangement that would cover all of the United Kingdom.

Under those arrangements, Northern Ireland would be aligned more closely with the EU's customs rules and production standards.

Any changes to or termination of those arrangements, after the end of the transition, would have to be agreed between London and Brussels.

Irish Prime Minister Leo Varadkar, whose desire to avoid a hard border was central for Brussels, said the deal satisfied all Dublin's key priorities.

But it remained unclear if the arrangement will pass muster in parliament as many pro-Brexit lawmakers demanded Britain must be able to unilaterally withdraw from the backstop to avoid being chained to the EU in perpetuity.

"I cannot support the proposed agreement in parliament and would hope that Conservative MPs would do likewise," Jacob Rees-Mogg, leader of an influential group of pro-Brexit Conservative lawmakers, wrote in a letter to his party colleagues.

Fisheries

The EU has said repeatedly that it would not allow British seafood exporters quota and tariff-free access to EU markets unless it is in exchange for a reciprocal agreement that EU fishing fleets are able to continue operating in British waters.

But the withdrawal agreement essentially goes only as far as to say that the EU would apply tariffs on fish until a separate deal was struck on access to EU fishing in Britain’s waters.

Citizens’ rights

Ending freedom of movement was a key demand for many who voted Leave, and will happen at the end of the transition period. Future immigration rules were not included in the negotiation process. This means Britain has flexibility to set its own.

The existing rights of the millions of EU citizens living in the UK and the Britons living in elsewhere in the bloc had already been guaranteed.

Transition period

Britain will leave the EU on March 29 but remain inside the bloc's single market and bound by its rules until the end of December 2020, while the two sides work out a new trade relationship. The transition period can be extended by joint agreement before July 1, 2020 if both parties decide more time is needed.

Divorce bill

Britain agrees to cover contributions to staff pensions and commitments to EU programmes the UK made while a member for the funding period that runs to 2020. The bill has previously been estimated at about £39 billion ($50 billion).

Difficult road ahead

The ultimate outcome for the UK remains uncertain. Scenarios range from a calm divorce to rejection of Mrs May's deal, potentially sinking her premiership and leaving the bloc with no agreement, or another referendum.

European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker recommended that EU leaders should go ahead with a delayed summit to rubber-stamp the agreement. This is likely to take place on November 25.

But EU chief negotiator Michel Barnier cautioned that the road to ensuring a smooth UK exit was still long and potentially difficult.

Mrs May, an initial opponent of Brexit who won the top job in the turmoil following the referendum, has staked her future on a deal that she hopes will solve the Brexit riddle: leaving the EU while preserving the closest possible ties.

But few are satisfied. Brexit supporters in Mrs May's party, which has been riven by a schism over Europe for three decades, said she had surrendered to the EU and that they would vote down the deal.

Opponents of Brexit say Britain will lose more than it can possibly gain from quitting such a big single market and political alliance. Some want another referendum.

Opposition Labour Party leader Jeremy Corbyn called it a "botched deal".

The Northern Irish Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) which props up May's government, said it would not back any deal that treated the British province differently from the rest of the United Kingdom.

They joined with Labour to cut the Government's majority to just five in a Commons vote on the Budget, and abstained on a series of other amendments to the Finance Bill on Monday night to send a "political message" to Mrs May over the agreement.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News