Bridget Riley: Five things you need to know

Painter Bridget Riley first entangled the eyes and muddled the minds of gallery goers over 50 years ago, when her illusion-inducing geometric paintings broke onto the 1960s art scene and became a global sensation.

Her paintings may have become visually synonymous with the Swinging Sixties, but Riley didn’t stop there.

After decades of producing major shows around the world and becoming one of the world’s most expensive living artists, the British painter will open an exhibition of recent work this week at the David Zwirner Gallery in Mayfair – at the age of 86.

Intrigued? This is what you need to know about Bridget Riley and her dizzying, disorientating and ultimately dazzling work.

Bridget Riley was a pioneer of a whole new art movement

By the time the 1960s came around, the allure of Abstract Expressionism’s inward-looking painterly paintyness was losing its grip on the art world. Artists began to reconsider what a painting could do to the outside world, and one movement looked to jump right out of the canvas and into your poor, confused mind. “Op Art” – short for Optical Art – rose to prominence and popularity in the early 1960s, using carefully designed geometric patterns to distort a viewer’s sense of space, distance and colour, many of which created the optical illusion of movement on the canvas.

The idea became so popular that the MOMA’s seminal show of Op Art, The Responsive Eye, sold out before it even opened. Following on from artists working at the Bauhaus school of art before the Second World War, and working in tandem with artists such as Victor Vasarely and Julian Stanzhak, Bridget Riley created some of the most captivating examples of the genre, and became one of the movement’s best known proponents.

She was a very astute art history student

Riley’s work may look like the pinnacle of mid-century Modernism, but these super slick, entirely abstracted paintings actually claim firm roots in the painterly experiments of the 19th century. While Op Art is most commonly illustrated by monochromatic works that deal with pattern and line in black and white exclusively, colour was a hugely important element in the work of many of its followers.

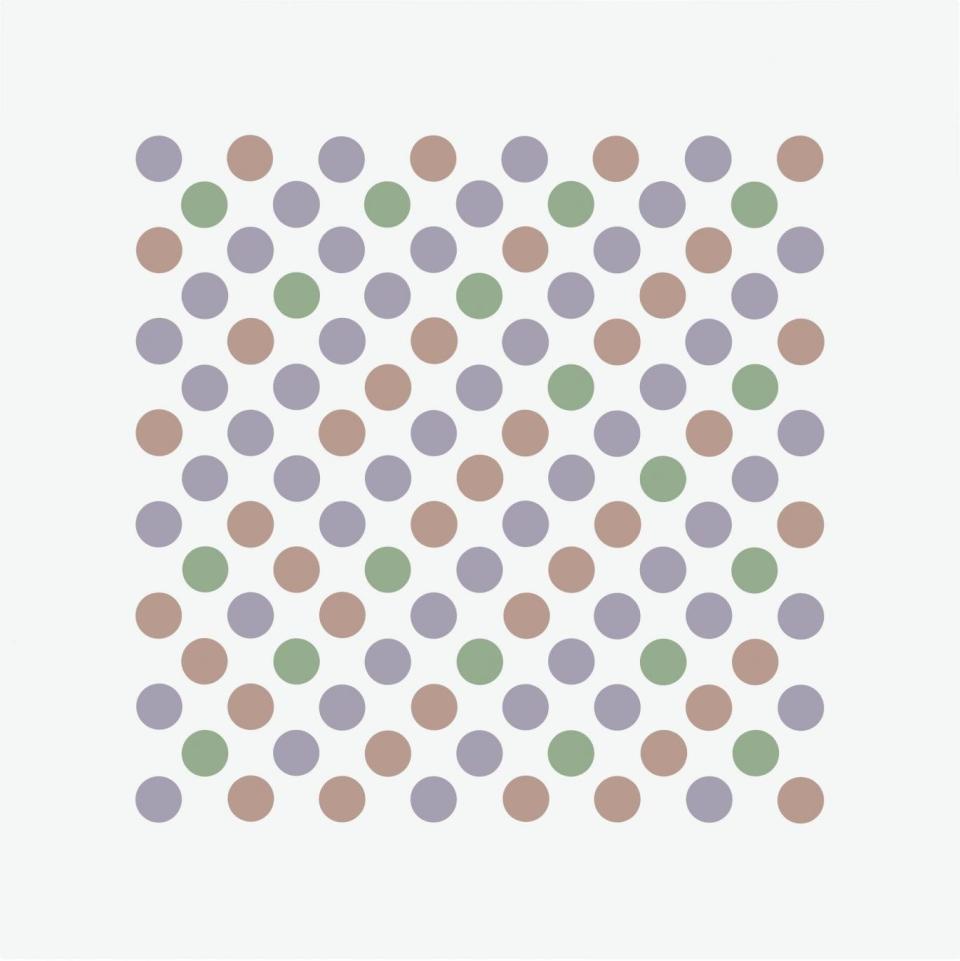

Bridget Riley is an extraordinary colourist, a skill that can be attributed to her dedicated study of Impressionist and Post-Impressionist artists. French painter Georges Seurat is one of her most fervent influences. Seurat was the undisputed master of Pointillism – a method of building form through the use of coloured dots – a style which Riley frequently emulated in student days. Riley then extrapolated this intricate study of colour into her abstracted work, using changes in colour to enhance and deepen the illusion.

Keith Moon wore her painting on a t-shirt while posing with The Who

Art, music and popular culture have perhaps never mixed as tenaciously as they did in the 1960s. In 1966, drummer Keith Moon was pictured with his band, The Who, wearing a t-shirt emblazoned with a painting by Bridget Riley. ‘Blaze’ features a series of concentric circles connected by black and white diagonal stripes – the effect makes the circles dance and twist and blur to the viewer. As they decrease in width to the centre, the viewer is drawn down the proverbial rabbit hole.

For many, the mind-bending nature of Riley’s paintings draws inevitable parallels to psychedelia and the drug culture of the 1960s. Op Art, however, is not Pop Art, and Riley has always been keen to emphasise the formality of her work and its philosophy over its links to popular culture. She even once lamented that The Responsive Eye exhibition at the MOMA was “obscured by an explosion of commercialism, band-wagoning and hysterical sensationalism”.

She once said that her gender is a “red herring”

Bridget Riley was one of the best known British artists working during the 1960s – and also happened to be a woman. Her prominence in the field during a pertinent time for Women’s Liberation created something of a complication for Riley. She had never associated her work with her femininity and did not wish to be critically characterised by her gender – calling it “a red herring”. She even once went as far to say of Women’s Liberation that “artists who happen to be women need this particular form of hysteria like they need a hole in the head”.

The acutely abstract nature of Riley’s work certainly distanced her somewhat from explicitly addressing her position as a female artist. “I have never been conscious of my own femininity as such, while in studio,” she once wrote. “Nor do I believe that male artists are aware of an exclusive masculinity while they are at work”.

She founded SPACE studios in London

Bridget Riley may have sold many millions of pounds worth of works, but back in the 1960s she was in the same predicament that many a London artist still find themselves today – seeking a studio that was both suitable and affordable. In 1968, Riley and fellow artist Peter Sedgely settled in a warehouse in St Katharine’s Docks. Inspired by the artist studios they encountered in New York, where both artists showed in The Responsive Eye, they founded the SPACE initiative, short for “Space Provision Artistic Cultural and Educational”.

Still functioning today, it is London’s oldest continuously operating artists’ studio organisation and a registered charity, presiding over 19 buildings across London and Colchester and running workspaces, artist residencies, exhibition space, bursaries and community projects.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News