Britain risks blackouts for industry if harsh winter strikes Europe

A harsh winter could force the UK to restrict business’ energy supplies shutting down factories in a throw-back to the three-day week of the 1970s, according to sector experts.

A spike in natural gas prices forced the business secretary, Kwasi Kwarteng into crisis talks with energy providers over the weekend. It has thrown the security of the country’s energy supplies into the spotlight, revealing vulnerabilities which government advisors claim to have repeatedly raised with government to no avail.

The business secretary emphasised the UK’s ability to produce nearly 50 per cent of the gas it needed last year in a statement to parliament on Monday and also suggested that key energy ally Norway could help meet shortfalls from elsewhere. He dismissed suggestions that there could be any supply shortages in the months ahead.

However, UK gas production has fallen this year and net imports of gas to the UK more than doubled in the three months to June compared to the same period in the previous year, the latest data released in August showed. Exports fell by more than three-quarters (76 per cent) and imports rose by 31 per cent during this period.

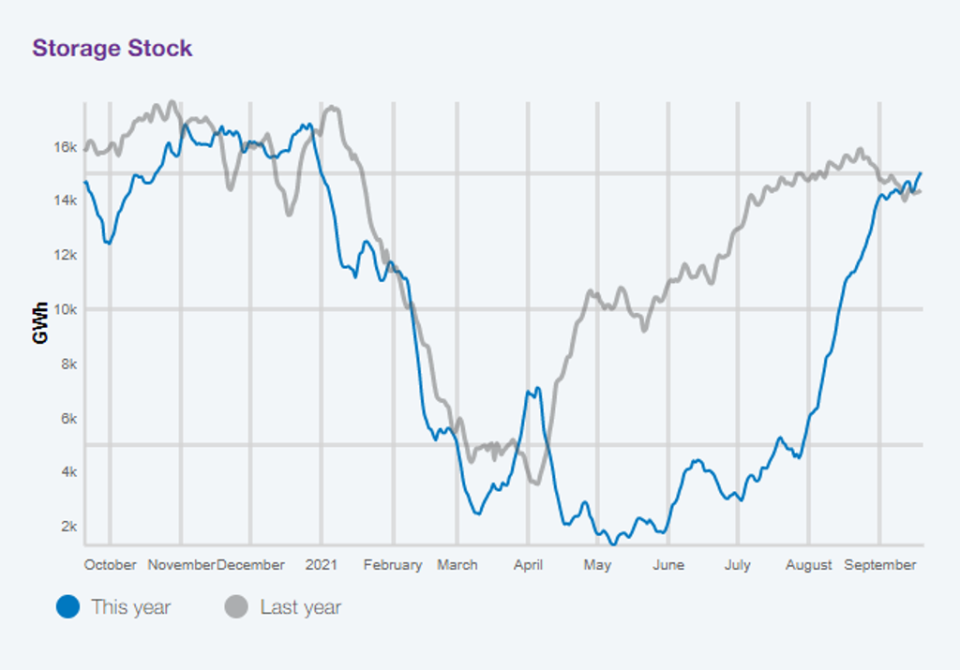

The UK’s gas storage would run low within weeks if there was a Europe-wide supply crunch triggered by a severe winter, according to academics and consultants who have advised the UK on energy security and market capacity. The supply crunch would most likely hit Britain in February and March: the worst months for storage levels in recent years, according to data gathered by the National Grid which overseas energy infrastructure.

Bad weather such as that seen in 2018 could leave the UK “at the mercy of global demand and foreign players”, said Nick Wye, director at energy consultancy Waters Wye Associates. “We [the UK] may find ourselves having to constrain supply for customers,” he said. There is a rapid decline every year in storage stocks through January and February, according to Mr Wye, and by March and February “this could mean very high prices, or at worst demand destruction and enforced curtailment”.

Further lockdowns due to a spike in Covid-19 hospitalisations could also put pressure on gas demand, with greater numbers working from home. This increased domestic demand for gas by 10 per cent in January 2021, compared to the same period in 2020, according to business department data.

Higher prices are a result of greater demand for gas in Asia as its industries recover from the pandemic, and reduced supply from the US of liquified natural gas, following Hurricane Ida. Meanwhile, production in the UK has fallen and Russia has shown reluctance to up its flow of gas to Europe via Ukraine. The UK can still get some supplies from Norway, which has signalled it will increase output.

Putting limits on the energy that companies can use hasn’t been commonplace in the UK since the 1970s, when a three-day week was introduced to conserve supplies of electricity which had been depleted by strike action at coal mines.

“From an industrial perspective the risk that we cannot ignore is that the price rises so high that it chokes off activity and the economic recovery,” said Ole Hansen, head of commodity strategy at Saxo Bank. “We could get to a point of rationing energy, and politicians don’t want people freezing in their homes so the other option is for industry to shut down.”

Energy-intensive industries would be the first to be impacted, Mr Hansen said, pointing to nitrogen fertiliser companies that suspended production last week. These concerns round counter to statements from the government on Monday after meetings with energy companies.

Mr Kwarteng said: “While we are not complacent, we do not expect supply emergencies this winter. This is a very important point: this is not a question of security of supply.

“There is absolutely no question of the lights going out or people being unable to heat their homes,” he said. “There is absolutely no question of the lights going out or people being unable to heat their homes. There will be no three-day working weeks or a throwback to the 1970s. Such thinking is alarmist, unhelpful and completely misguided.”

An emergency plans produced by the UK’s business department in November 2019 details the steps that the UK’s business secretary will have to follow if the country might soon run out of gas. There are four levels of an energy crisis from normal (white) through to emergency (red). A government spokesperson reiterated the business secretary’s claim that it did not expect supply emergencies this winter.

At the red level, “non-market measures have to be introduced”, which a person famliar with the plan’s development said would include restricting energy use by energy intensive industries. This would likely require a reduction in the hours those businesses would operate until supplies were normalised and stores started to be refilled. The Foreign Office would have to oversee any formal requests for international support, according to the plan.

Fears of a Europe-wide energy crunch have drawn fresh attention to Russia’s role as a major gas producer. Its output could prove crucial this winter, Mr Wye and other experts warned. If the country chooses to limit supply to Europe, it could exacerbate price rises, and potentially drive shortages. Poor weather in the US, including Hurricane Ida, has also curtailed production of Liquid Natural Gas, an increasingly important source for the UK according to the government’s 2020 Security of Supply report.

Recent auction data, gathered by Bloomberg, suggested that Russia is holding off increasing supplies to Europe, even in the face of a price spike. Gazprom, the Russian state-owned company, has not booked any additional room for transporting gas to Europe via Ukrainian pipelines, the auction data for October released on Monday showed. This decision caps a key mode of gas supply just as countries are looking to build up stores ahead of winter.

Yet the business secretary also tried to dispel concerns that the UK would be at the mercy of Russian production. He said he had been in contact with his Norwegian counterpart, and noted that the country, which accounts for nearly 30 per cent of UK gas supply, would be increasing its production. He said that Norway had promised to sharply increase supply from 1 October.

Soaring gas prices have already caused factories to close. Two fertiliser production sites in the UK, both owned by US-based CF Industries, have halted operations citing gas costs. These plants generate 60 per cent of the UK’s carbon dioxide supply, a key input for meat production, as it is used to stun animals for slaughter and package food.

Gas stores across Europe are also at relatively low levels going into winter and the UK’s largest gas storage facility, the Centrica-owned Rough site, was closed in 2017. This has increased the UK’s dependency on gas imports, leaving more exposed to a global, or regional, supply crunch. Any energy shortages impacting the UK would likely also hit Ireland hard, as the countries’ supplies are closely integrated.

The sharp rise in gas prices has pushed some domestic energy retail companies out of businesses already. However, the government said on Monday that it would not bail out energy firms who can no longer afford to operate in the face of higher costs. These companies had largely failed to hedge enough of their customers’ energy needs going into the winter, leaving themselves exposed to sudden shifts in energy prices.

But it is not yet clear how the customers left behind by these companies’ closures will be managed. While their energy bills will be limited by the government’s price cap, other energy companies are unwilling to take on these customers unless they get financial support from government to meet the steep costs of customers’ energy needs.

A ready reckoner of how companies tackle hedging supplies is to buy a year’s worth of energy per customer, although in practice with a large portfolio of customers this can be more complicated. Even with very careful hedging of large portfolios, a sustained increase in gas prices will put pressure on energy companies’ profits, putting the long term viability of the government’s present price cap in question.

If the government decides to use other companies to fill in for customers, as has been done before, companies stepping in to bridge the gap expect to be given financial support, according to people familiar with meetings between suppliers and the business department. The details on how this arrangement will work are still not certain, the same people said.

In nearby countries, governments are stepping in to cushion the blow, but “higher energy bills are a downside risk to the eurozone’s consumer recovery”, said Jessica Hinds, Europe economist at consultancy Capital Economics. France’s government has offered an £86 (€100) subsidy on energy bills this winter for the poorest households, while Spain’s has announced it will cut household energy bills to 2018 levels.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News