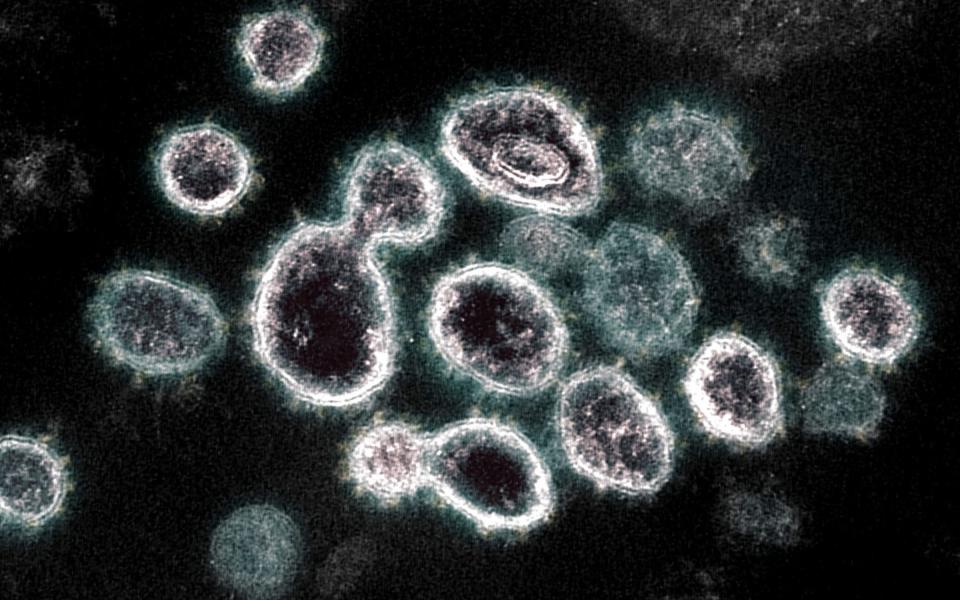

How British experiments risked making the Covid pandemic ‘more lethal’

British scientists carried out experiments that risked creating more dangerous variants during the pandemic, it has been claimed.

In testing led by Imperial College London and supported by the UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA), cells were infected with delta and omicron at the same time to see which had a competitive advantage.

Anton van der Merwe, professor of molecular immunology at the University of Oxford, said that such experiments risked combining the two variants to produce something “more lethal” that could have infected scientists or leaked from the laboratory.

“Coronaviruses like Sars-CoV-2 are well known to ‘evolve’ by exchanging genetic material when two distinct viruses infect the same cell,” he said.

“This makes it much more likely that these strains will ‘recombine’ and create a more dangerous variant, which could infect those doing the experiments, who could then spread it into the community.”

Experiments 'in line with strict regulations'

Prof van der Merwe said using delta and omicron was particularly risky because they were from different lineages and had more differences than those variants closer to the original Wuhan strain.

Imperial College London defended the experiments, which took place in London, arguing that they were needed to inform the pandemic response. It added that they were carried out under high biosafety standards.

A spokesman for the university said: “This government-backed research used viruses no more pathogenic than those already circulating within the population and will provide crucial insights that support government decision-making on how to manage the pandemic.

“It was conducted in a biosafety level three laboratory in line with strict government regulations, and received ongoing approval from the Health and Safety Executive.”

Since the start of the pandemic, there have been fears that Covid-19 leaked from a laboratory in Wuhan, where researchers were carrying out experiments on bat coronaviruses.

In recent decades smallpox, swine flu, sars, and anthrax, as well as foot and mouth disease, have escaped through laboratory leaks.

This week, a report by King’s College London warned that laboratories containing dangerous pathogens are increasing. Three-quarters of maximum security facilities are now located in urban areas, increasing the risk of a leak.

'Risky research'

Report authors said that many countries are conducting “risky research” that could lead to the “accidental or deliberate release of a pandemic-capable pathogen”.

Dr Filippa Lentzos, co-director of the Centre for Science and Security Studies at King’s College London, said: “There has been a global boom in construction of labs handling dangerous pathogens, but this has not been accompanied by sufficient biosafety and biosecurity oversight.”

Prof van der Merwe has argued previously that many scientists were reluctant to consider the possibility that a laboratory leak started the pandemic for fear of having to curtail their own risky viral experiments.

He discovered that in a separate experiment in Germany, scientists carried out similar tests as Imperial using the alpha and beta variants on hamsters, ferrets and humanised mice.

The paper, published in Nature, was led by Prof Lorenz Ulrich, now at the Friedrich-Loeffler-Institute, Greifswald. It was co-authored by Christian Dorsten, of Charité – Berlin University of Medicine, who signed a letter in the Lancet in 2020 dismissing the possibility that Covid-19 could have leaked from a laboratory.

“There is more opportunity for recombination in animal experiments and selection for more dangerous variants because they involve more cells infected for longer periods,” added Prof van der Merwe

“Handling animals is also riskier in terms of transmission to the experimenter than handling cells.”

He added: “Neither of these experiments are of any help in protecting us from Sars-CoV-2.

“If it was conclusively proven the Sars-CoV-2 pandemic was a result of a laboratory leak it would obviously strengthen that case for stricter global regulation of experiments on potentially dangerous pathogens.”

The UKHSA was approached for comment but said it had nothing more to add beyond Imperial’s response. The Friedrich-Loeffler-Institute had not responded at the time of publication and Charité – Berlin University of Medicine declined to comment.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News