How British prisons became a breeding ground for Islamist extremism

When Naweed Ali, Khobaib Hussain and Mohibur Rahman met up in Belmarsh prison in 2013, they had already broken terror laws.

But it was not until after their beliefs were reinforced, as they mingled with fellow extremists in jail, that they turned their attention to wreaking bloodshed in the UK.

Dubbing themselves as the “Three Musketeers”, they were poised to strike police and military targets in the UK using a pipe bomb and meat cleaver until the security services intervened.

The terror plot was not the first to have been spawned from extremist networks formed in Britain’s prisons, and experts fear it may not be the last, as record number of terrorists are jailed.

The government has been intensifying efforts to prevent jihadis from spreading their influence on the inside, and monitor them when they are freed, but the methods have not been tested.

Rajan Basra, a research fellow at the International Centre for the Study of Radicalisation (ICSR) at King’s College London, said it was “very difficult to gauge what’s happening inside prisons”.

The academic, who has carried out research on the interplay between criminality and terrorism across Europe, said Britain is among several countries working to disperse low-level terror offenders throughout jails, while putting the most dangerous prisoners in separation units.

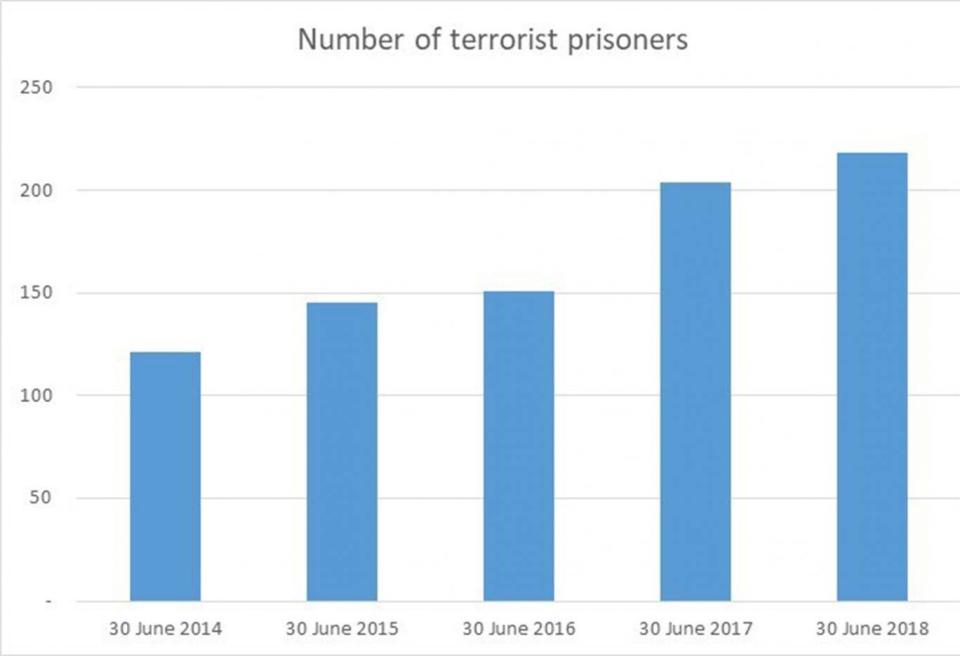

“We are seeing a great experiment take place where we’ve got more extremists behind bars than ever before, they’re often on pretty short sentences and no one knows what is the most effective way of managing them,” Mr Basra told The Independent.

“There has been no public evaluation of how effective these measures are and I’m not sure there’s been many internal ones either.

“Separation centres and isolating the most charismatic prisoners sound like good policies but we have to see how effective it is, and my concern is that we don’t know if what we’re doing is the best practice.”

Sara Khan, the lead commissioner for Countering Extremism, said extremism in prisons had been raised as an issue during a nationwide study of all types of radicalisation.

“Experts and those working in prisons have raised significant concerns with me about the spread of extremist ideas and behaviours among serving prisoners,” she told The Independent.

“This includes the risk that individuals are becoming more extremist in prisons. There are also fears about what happens when prisoners who advocate extremist beliefs and behaviour – whether Islamist or far-right supporters – are released into our communities.”

The government says it is training thousands of staff on how to spot extremism and that probation officers, the police and security services, liaise over any potential threat after terrorists are freed.

A joint HM Prison and Probation Service and Home Office extremism unit was created in April 2017 to lead the response in prisons and probation and a new national intelligence unit is working in jails.

But the processes are coming under scrutiny in the ongoing inquests into the deaths of victims killed in the Westminster terror attack.

The Old Bailey has heard that Khalid Masood appeared on MI5’s radar shortly after being released for his connections to a terrorist network that was plotting bombings in the UK.

His mother said he would go "on and on and on" about Islam after he converted in prison, where he had been serving time for a violent attack.

Masood continued appearing as a contact of terrorists, including those linked to Anjem Choudary’s al-Muhajiroun network, but was never considered an imminent threat.

Choudary himself is soon to be released from prison after serving a sentence for inviting support for Isis, and the justice secretary has pledged that he will be “watched like a hawk” and put under strict licence conditions limiting his behaviour.

More than 260 terrorist prisoners have been released since Isis declared its “caliphate” in 2014 and there are 228 people currently in prison for terror-related offences – 82 per cent Islamist, 13 per cent far-right and 6 per cent “other”.

The Ministry of Justice (MoJ) says it is managing a far larger number of prisoners – 700 – under a “counterterrorism specialist case management process” and a prison officer told The Independent that the figure “doesn’t come anywhere near” the real number of radicals inside.

A review of Islamist extremism in prisons, probation and youth justice that was commissioned by the government in 2015 found it was a “growing problem”.

Its full findings were classified, but a summary said the rising number of prisoners on short sentences for lower-level terror offences, like possessing terrorist information or disseminating publications, “extend the threat of radicalisation beyond those arrested for terrorist offences”.

The report warned that non-terrorist prisoners and non-Muslims were vulnerable to radicalisation and "Muslim gang culture”, violence and drug trafficking.

It found evidence of “aggressive encouragement of conversions to Islam”, prison staff being pressured to leave Friday prayers, extremist prisoners segregating inmates and intimidating moderate imams.

Ian Acheson, a former prison governor who led the review, told The Independent that a “lethal combination of arrogance and ineptitude at the top meant that the scale of the problem was not remotely understood”.

“We have no clear idea what impact long-term custody will have on the ideological commitment of these people,” he added.

The prison officer, who works in a high-security estate and spoke on condition of anonymity, said the proportion of “real Muslims” in jails was lower than the number declaring themselves as followers of the religion.

He described people who join gangs as “plastic Muslims”, adding: “Some of them are just the hanger-ons, they agree to join the club but they don’t really want to be part of it.”

Mr Basra predicted that many of the inmates, who associate with radicals on the inside, may “disengage” after being freed and not pose a threat.

“They can do it for safety, because they’re going through an existential crisis or because they’re coerced,” he added.

“Their radicalisation may subside when they go back to regular life but there’s no way of knowing after monitoring stops.”

A report he co-authored on the “Crime-Terror Nexus in the UK and Ireland” warned that Isis had embraced criminals to bring into its ranks, alongside their skills at subterfuge, obtaining weapons and predilection to violence.

It found that a “substantial cohort” of British jihadis are believed to have convictions for crimes unrelated to their extremism, adding: “In British prisons criminal and terrorist milieus have connected and cross-fertilised. Prisons are like microcosms of the crime-terror nexus where radicalisation, recruitment, networking, and even terrorist plotting have taken place.”

The government’s contest strategy includes a desistance and disengagement programme that aims to rehabilitate terrorists with mentoring and psychological support as well as theological and ideological advice.

The Home Office is also establishing a series of experimental multi-agency pilots testing different models to better understand the risk posed by people previously judged a threat.

A prison service spokesperson said: “We are doing more than ever to counter the spread of extremist ideology in our prisons. This includes opening two separation units to hold extremist prisoners and training more than 17,000 staff to deal with extremist behaviour.

“We also recognise the need for stability, which is why we are investing £40m to improve the prison estate and tackle the drug problem, which is fuelling much of the violence, as well as recruiting 3,500 new officers.”

Yahoo News

Yahoo News