What is California's wildfire smoke doing to our health? Scientists paint a bleak picture

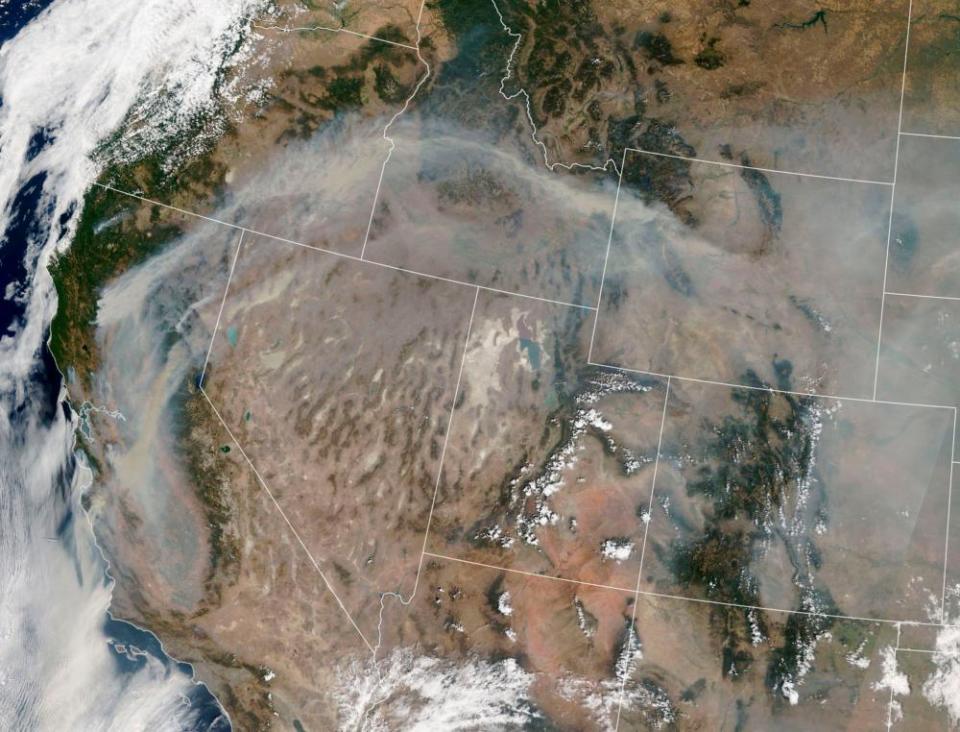

Historic wildfires burning across California have sent a 500-hundred-mile-long, gray blob of smoky air swirling above the western United States, and Stanford researcher Bibek Paudel is already seeing the health effects build up.

In the days after lightning sparked hundreds of fires across the north of the state, Paudel, who studies respiratory illness at Stanford’s allergy and asthma research center, saw hospital admissions for asthma to the university’s healthcare system rise by 10% and cerebrovascular incidents such as strokes jump by 23%. Based on the center’s studies of recent fires, Paudel expects that the number of heart attacks, kidney problems and even mental health issues will also climb.

The research is part of a growing body of scientific evidence painting a dire picture of the effects of wildfire smoke on people, even those living hundreds of miles away. Many researchers worry that those debilitating effects will only intensify the risks of the Covid-19 pandemic. “Wildfire smoke can affect the health almost immediately,” said Dr Jiayun Angela Yao, an environmental health researcher in Canada.

Related: ‘An impossible choice’: farmworkers pick a paycheck over health despite smoke-filled air

This summer, Yao co-authored a study for the University of British Columbia showing that, within an hour of fire smoke descending upon the Vancouver area during recent wildfire seasons, the number of ambulance calls for asthma, chronic lung disease and cardiac events increased by 10%. The study found that within 24 hours greater numbers of people were calling for help with diabetic issues as well.

Studies after the bushfires that raged throughout Australia last year found even bleaker outcomes. Researchers from the University of Tasmania identified 417 extra deaths that occurred during 19 weeks of smoky air, and reported 3,100 more hospital admissions for respiratory and cardiac ailments and 1,300 extra emergency room visits for asthma.

The fires and the smoke are complicating the response to the coronavirus pandemic. Meanwhile, social distancing requirements are exacerbating the risks of smoke pollution. “For communities that are exposed to both fire smoke and Covid-19, it’s going to be a double threat,” Yao said.

For health workers and first responders, dealing with both a pandemic and a fire season at the same time comes with significant logistical challenges. Evacuees and firefighters forced to live in shared housing may face additional Covid-19 exposure. The pandemic has already stretched the resources available from local government agencies thin.

Residents wanting to get away from the smoke may no longer have the option of sheltering at the library or mall or staying with friends because of shut-downs and pandemic risks. “We are not in a situation where people can just leave to get away from the smoke as they might like,” said Peter Lahm, an air resource specialist with the USDA Forest Service, who specializes in monitoring wildfire smoke.

Researchers also fear the smoke can act more deeply to hamper the body’s ability to fend off infection.

Science has long shown that air pollution can cause numerous deadly health effects, including increasing the severity of respiratory infections, such as flu and pneumonia. Research this year from Harvard University showed a significant link between increases in long-term exposure to air pollution particles and Covid death rates. The study, led by researcher Xiao Wu, has not yet been peer reviewed.

Many US regions have managed to reduce pollution from industrial smokestacks and automobile tailpipes, but wildfire smoke has become an increasing threat.

Fire smoke is a volatile mixture of gases that can contain hundreds of different toxins, depending on the heat of the fire, the wind conditions and the composition of what is burning – whether it is trees, grasses or houses filled with plastics and manmade chemicals.

The spray of very fine particles – known as PM2.5 – that wildfires launch into the air causes the biggest concerns. These particles are small enough to be inhaled through the lungs, where they can cause disruptions to health that are just beginning to be fully understood.

“We know that pollution, in general, is going to make your immune system less healthy and its responses more chaotic,” said Dr Mary Prunicki, who oversees Stanford’s smoke studies as the director of research for the Sean N Parker Center for Allergy & Asthma Research. “It requires a healthy immune system to fight infections like Covid-19. And, if your immune system isn’t working as well, it puts you at greater risk.”

Prunicki and her team are working to learn more about how wildfire smoke affects the workings of the human body. Even as her own home was threatened with possible evacuation from Santa Clara county’s SCU Lightening Complex fires, Prunicki was working to send out more than 100 blood testing kits to volunteers for a study that researchers hope will help establish how conditions like inflammation are affected by the smoke.

Earlier studies of young people, who were exposed to even distant wildfire smoke, showed dramatic changes.

“We found, even in teenagers, if we drew their blood after a wildfire, we saw a systematic increase in inflammatory markers,” said Prunicki, who added that “a lot of chronic disease is related to inflammation”.

With clouds of smoke from the fires floating around the country, people as far away as Idaho and Colorado are choking on California’s smoke. “We had several days when we were just socked in,” said Sally Hunter, an air specialist with the Idaho Department of Environmental Quality, who said smoke travelled north to spark health warnings in Boise, even though there were no fires nearby. “I got up to go get groceries and I couldn’t see down to the end of my street. I got a headache and my sister in-law got itchy, watery eyes.”

Since California’s fires started months earlier than usual, experts worry that this will be an especially smoky year.

The worst year on record for California fire smoke was 2008 when lightning fires started in June and continued all summer, according to Lahm. Fires from 2017 and 2018 also unleashed huge amounts of smoke.

Paudel and the Stanford researchers found that, since 2011, the number of smoky days occurring each year has increased in California and in the entire western US. Unfortunately, some of the largest increases were in counties with the biggest population centers, such as those around Los Angeles or along California’s central valley.

When a gray curtain of smoke descended on the Bay Area last week, 76-year-old Berkeley resident Barbara Freeman, who suffers from pulmonary conditions, tried to follow all the advice. She regularly checked environmental air monitor readings, stayed inside, sealed her windows and turned on her two air cleaners.

Still Freeman lost her voice and found breathing painful. She worried, if she had to evacuate, she would have nowhere to turn to escape both the smoke and the danger of coronavirus. But one of the things she found the hardest was not being able to go outside to walk her dog.

“That was how I was maintaining what sanity I had left,” she said.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News