The camera that can see INSIDE a beating heart - developed by research team in London

London researchers have invented a camera that fits on the end of a needle and can provide live images from inside a beating heart.

The extraordinary breakthrough could transform the safety and speed of cardiac keyhole surgery, including procedures performed on thousands of patients a year.

It could also be used in neurosurgery, operations on babies in the womb and to position epidural injections given to women in labour.

At present, cardiologists rely on external ultrasound scans and “educated guesswork” while treating conditions such as atrial fibrillation, a common condition that causes the heart to beat faster than normal, or mitral valve disease, which damages the heart’s plumbing.

A key part of the treatment involves passing a needle from the right to left chamber, which can have “disastrous consequences” if done incorrectly and the heart wall is pierced.

The camera, which measures less than 0.5mm across, has been created by researchers at University College London and Queen Mary University of London (QMUL).

It is so small that it can be inserted onto the tip of catheters used in heart procedures and other tiny surgical instruments.

The camera, which has been four years in development, has been tested in heart surgery on pigs. The team hope to launch the first trials in humans in 18 months.

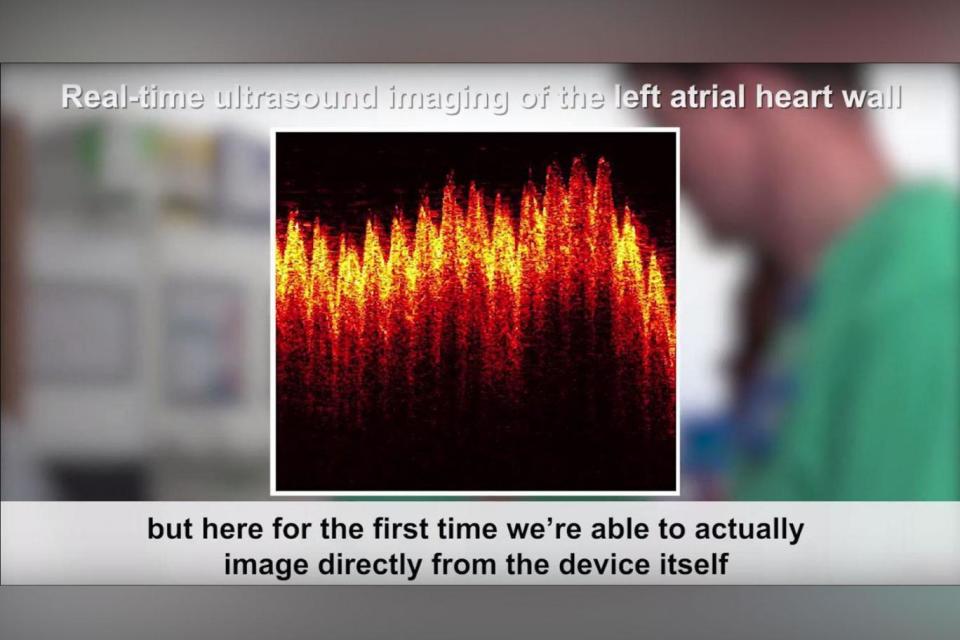

It is the first camera the world to use optical fibres rather than electrical pulses to generate images from inside the heart. It gives an unprecedented, high-resolution view of soft tissues up to 2.5cm in front of the instrument.

Dr Malcolm Finlay, study co-lead and consultant cardiologist at QMUL and Barts Heart Centre, said the images were “better than we had even hoped”.

He said: “To have direct imaging from the device is obviously a huge step forward. In many minimally invasive procedures we are reliant on imaging taken from outside the body.

“But here for the first time we are able to actually image directly from that device itself. It’s as if you are inside looking at what the devices inside the body are actually going to touch and do.”

He added: “The optical ultrasound needle is perfect for procedures where there is a small tissue target that is hard to see during keyhole surgery and missing it could have disastrous consequences.

“We now have real-time imaging that allows us to differentiate between tissues at a remarkable depth, helping to guide the highest-risk moments of these procedures.”

About 6,500 heart ablations are performed each year in the UK to treat atrial fibrillation, almost 1,000 of them at Barts Heart Centre.

However doctors estimate the demand for the procedure, which uses radio waves or freezing to create scar tissue to stop the heart “firing off” extra pulses, is 10 times greater.

Many patients are put off by the risks of the operation, which is also less likely to be performed in local hospitals rather than specialist centres.

Dr Adrien Desjardins, study co-lead from the Wellcome EPSRC Centre for Interventional and Surgical Sciences at UCL, said: “This is the first demonstration of all-optical ultrasound imaging in a clinically realistic environment.

“We now hope to replicate this success across a number of other clinical applications where minimally invasive surgical techniques are being used.”

The camera emits a brief pulse of light, which generates ultrasonic pulses. Reflections of these ultrasonic pulses are detected by a sensor on a second optical fibre in the camera, creating the images. The findings were revealed today in the journal Light: Science & Applications.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News