Celebrity train wrecks fascinate and appal. But could they be our fault?

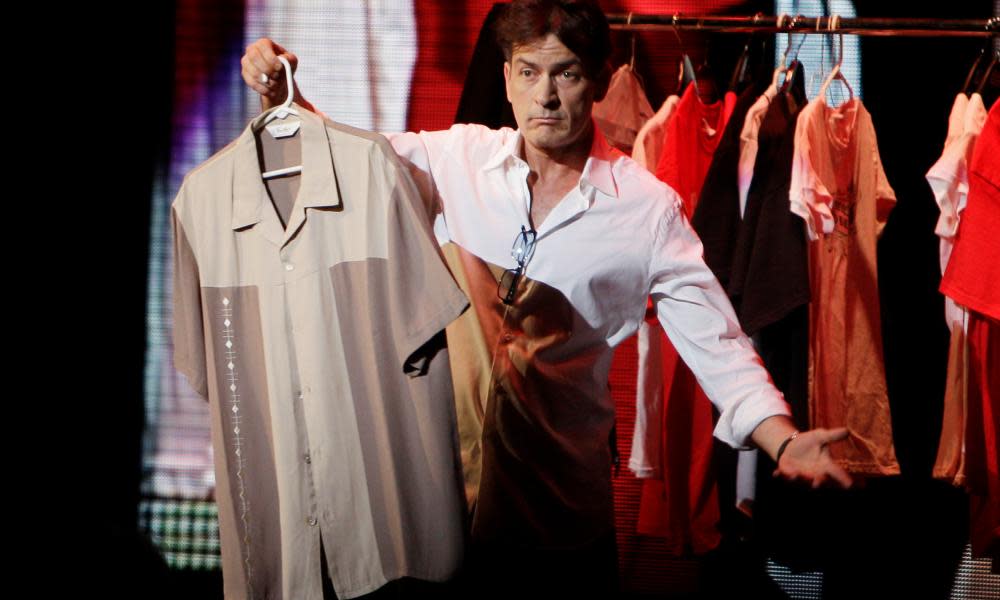

Nine years ago, I flew to Detroit for what had by then become an international spectator sport: watching Charlie Sheen have a mental breakdown. In the previous months, Sheen had gone from “beloved bad boy cheeky chappie” to shattered wreck. He posted unhinged webcam videos in which he claimed to have “tiger blood”, and these proved so popular that he took the show on the road, in a tour titled Violent Torpedo Of Truth/Defeat Is Not An Option.

As a child, my parents took me to what was then the USSR, and we visited the Moscow State Circus. No one goes to a circus expecting to see happy wildlife, but the Moscow State Circus in 1988 took it to the next level. The animals were ragged, their fur patchy. I enjoyed a bear on a bicycle as much as the next 10-year-old, but watching that muzzled animal, so thin and bald I could see his bones working as he frantically pedalled, tested even my enthusiasm. Meanwhile, the crowds bayed.

It’s rare that you experience the literalisation of a cliche, so I long assumed that this was as close to bear-baiting as I would get. And it was, until I sat in the audience of Sheen’s tour. Sheen, who has since said he’s bipolar and HIV positive, lurched around the stage while the crowd called for anecdotes about porn stars and crack. When he failed to provide to their liking, they booed. Afterwards, I asked some audience members what they thought. “I wanted to see a train wreck. [But] I thought he’d be funnier,” one told me.

It is no revelation that being famous is rarely conducive to good mental health, nor is wanting to be famous generally a sign of personal stability. As a result, celebrity train wrecks come along with the regularity of actual trains, and yet they still fascinate, like a bear on a bicycle. Britney Spears shaving her head; Amy Winehouse in blood-stained ballet slippers; David Hasselhoff drunkenly trying to eat a cheeseburger while talking about loneliness – all of these happened in full view of the public, and we, the public, made them iconic, referencing, satirising and, later, meme-ing them into posterity.

Kanye West has long been an anomaly: a celebrity who goes off-script in an era when even “reality” TV shows have screenplays. Sometimes this has been for the good, such as in 2005 when, while raising money for victims of Hurricane Katrina, he announced on TV, “George Bush doesn’t care about black people.” At the time, he was pilloried, but now he would probably get his deserved plaudits. (I would like to take this moment to add that he was also right in 2009, when he said that Beyoncé’s still legendary Single Ladies video should have won the MTV Music award, and not Taylor Swift’s You Belong With Me. But this topic may still be too controversial to discuss.)

Sometimes, especially since the death of his mother, Donda, in 2007, this going off-script has been for the less-good. The footage last month of West launching his presidential bid by talking about the time God told him through his laptop not to abort his oldest child (a sentence not even Hunter S Thompson could have come up with at his most hysterically surreal) did not suggest he is an entirely well man. As I write, his wife, Kim Kardashian West, has released a statement acknowledging her husband’s bipolar disorder and pleading for “compassion and empathy”. It feels especially poignant that this episode should have happened the same week West released his new album, Donda, named after his mother.

For all the talk these days about mental health, fans have a push-pull-push relationship with the mental health of celebrities. Women are envied for their extreme thinness, and then snarked at for looking anorexic; child stars are celebrated for faking emotions, and then derided when they grow up and have a confused relationship with reality, as detailed in the fascinating recent documentary Showbiz Kids, by former child actor Alex Winter. This was also gently touched on in Judy, last year’s biopic about Judy Garland, in which fans are shown alternately loving Garland for her frailty and then resenting it when she can’t sing about that rainbow again. It’s a dynamic that would be familiar to many other stars, from Marilyn Monroe to Pete Doherty. Train-wrecks are fun, as long as they’re still sexy, cool and funny.

When I interviewed Sheen in 2016, I asked him whether the public’s expectations exacerbated his behaviour. “I think it led me to being something I wasn’t,” he said. “I guess it comes down to a measure of people-pleasing,” he said. Sheen took his bad-boy image to the extreme endpoint; Garland never stopped being a helpless little girl, to the delight and frustration of those around her; West is the brave truth-teller. As bystanders, we are fascinated, then mocking, then disgusted. But aren’t they just giving us what we want? Given how frequently this happens, and how we are surprised by it, again and again, you have to wonder.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News