A century of adult education has been tossed aside – is it too late to rescue it?

The face of a man I met just once, 15 years ago, still haunts me. He was around 40, pale and thin, with no distinguishing features beyond obvious exhaustion. I was working in the enrolment office at a further education college when he slumped into a chair opposite my desk.

“I want to retrain,” he told me. “As what?” I asked. “As anything,” he said. Good at school, he had dropped out early to become a builder and earn his family some cash. Now a foreman, he wanted more from life: to be a teacher, or an accountant, or anything that didn’t involve heaving pallets from place to place.

With two children and a mortgage, he couldn’t afford to stop working or take a lower salary. Looking at the course catalogue in front of us, his options were limited. A-levels didn’t lead directly to a new job; book-keeping ran in the daytime; degrees were a distant dream.

As the search became frantic and hopeless, he became dejected. “What now?” he asked, his eyes filling up. “Am I stuck in this life for ever?” My 20-year-old self squirmed and stared at my keyboard. All the lies in the world couldn’t cover up that he was.

Did he ever make it out? I thought of him again last week when an email informed me it is 100 years since the Ministry of Reconstruction published the 1919 Report on Adult Education. Back then, politicians worried that extending the vote meant the public needed to be smarter, or they would be taken in by populist demagogues. Looming industrial and technological change meant Britain needed to re-skill its workers, double-time.

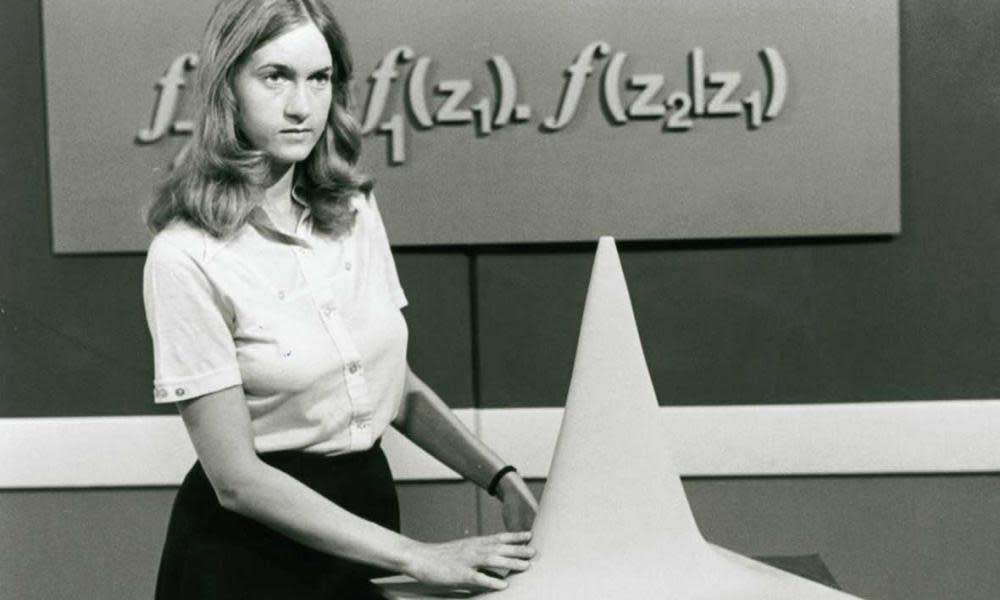

Local councils were granted responsibility and cash for adult education. Night classes flourished in sewing, budgeting, car repair. By the 1960s and 70s innovations such as the Open University and the BBC’s On The Move sitcom, featuring adults with literacy problems, suffused learning into every part of the country’s culture.

When I started my A-levels in 1999, through night school while working at McDonald’s, I benefited from an 80-year tradition that gave British people the means to educate themselves out of a life they didn’t want any more.

We have thrown this all away. The Open University has become outrageously expensive after the government swiped its subsidies. Night schools have dried up. Apprenticeship wages are held at £3.70 an hour, less than I was paid in McDonald’s 20 years ago.

Meanwhile, the average 40-year-old faces a sky-high mortgage and the threat of a robot replacing them at work. Their pension, however, won’t kick in until at least 68. Workers aren’t just stuck in their lives; they are knee-capped from escaping.

Thankfully, a new centenary commission, led by the Co-operative College, the Workers’ Educational Association, and the Universities of Oxford and Nottingham, is forming to find solutions. It will report back in November. No doubt there will be the usual calls for more cash and kudos in adult education.

Neither, however, helps, unless it goes straight to the learner. If I could travel back in time, I wish I could have offered my bashful builder access to an individual learning account, which would be credited by the government with three years of learning at 16, plus two at age 40, and another two at 60. The credits could be used at any point to access courses or to boost an individual’s wages while retraining. And if my builder been made redundant after his job was outsourced or automated, the employer would be required to pay a “robot levy”– a year of credits into his account as part of his pay-off package.

I have no doubt that if this was a government policy, then or now, that builder would put blood, sweat, and tears into his education. We would probably have a great new teacher working in our classrooms.

The poet WH Auden once said: “All that we are not stares back at what we are”. I hope that the builder made it into a new working life. I hope the commission helps many more people to do so, too.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News