Cherry Jones: ‘All of the adults have left the room in America, and maybe in most of the world now’

To talk to Cherry Jones about anything at all is to end up talking politics.

I don’t get the sense that she’s trying to be political, just that everything that interests the actor – about the art she makes, about the people she knows, about the fact I have a young child, about conversation itself – is inherently political.

She conceives of her new Apple TV+ mini-series Five Days at Memorial – a ripped-from-the-headlines survival drama about Hurricane Katrina – as, implicitly, a climate-change call to action.

When I ask about her Succession character Nan Pierce – the matriarch of a media family who goes head-to-head with Brian Cox’s Logan Roy – her associations lead straight to the US capital and the first-ever female publisher of The Washington Post.

“So is she sort of a wannabe Katharine Graham?” Jones asked when she was offered the role.

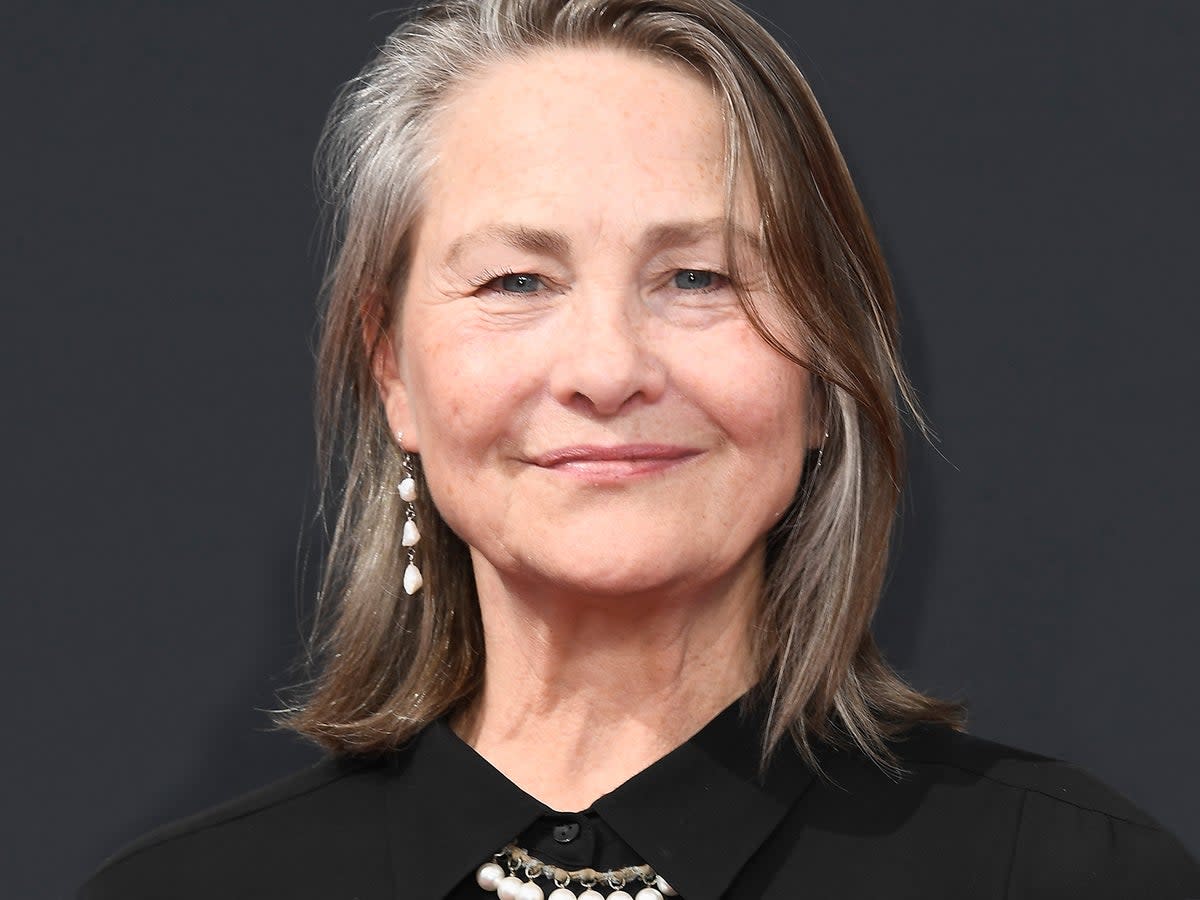

The 65-year-old actor with the dark silver bob and warm Tennessee lilt has long been considered one of her generation’s greatest stage actors, with Tony awards for her 1995 turn in The Heiress and another for originating the terrifying role of Sister Aloysius in Doubt, a thunderous play about the Catholic Church’s sexual abuse scandal – and later a Meryl Streep movie.

But over the past decade, she’s also emerged as a go-to star for TV’s most politically ambitious projects: the HBO media dynasty drama Succession, for which she won her third Emmy. Hulu’s dystopian smash The Handmaid’s Tale (second Emmy).

Amazon’s ground-breaking comedy Transparent. Still, for many audiences, Jones remains most recognisable as President Allison Taylor from 24, the slick network drama about an ethically dubious counter-terrorism agent. Emmy #1, if you can believe it.

On Five Days at Memorial, a series based on New York Times reporter Sherri Fink’s bestseller, Jones plays real-life nursing coordinator Susan Mulderick.

She happened to be serving the rotating post of “incident commander” on the 2005 weekend Katrina hit Memorial Medical Centre in New Orleans, which means Mulderick was the one responsible for the lives of more than 2,000 people. That included patients, their families, doctors, and citizens who’d turned up to the hospital looking for shelter.

What happened next should be the stuff of fiction. Memorial survived the initial storm, but when the city’s levees broke, flooding killed the hospital’s back-up generators. Inside the building, as temperatures soared past 100F, Mulderick was responsible for answering an unimaginable array of what-ifs.

What if we run out of medicine? What if we run out of water? What if no one comes to save us? Tellingly, the hospital’s only evacuation plan took for granted that the land around the mammoth facility would be dry as a cracker.

Jones was doing Doubt when the storm hit, but she still remembers watching the news coverage each night. She remembers watching the death toll rise, eventually to more than 1,800 fatalities.

She remembers people standing on their roofs trying to flag down rescue helicopters. She even remembers what she was thinking: “This only happens in a third world country.”

When Jones saw the “tremendous” script for Five Days at Memorial, from 12 Years a Slave writer John Ridley and Lost showrunner Carlton Cuse, those memories came rushing back, mixing with new concerns about the current shape of American democracy.

It’s a sense of alarm informed by inaction on climate change, the Black Lives Matter protests, and the nation’s response to Covid. “There have to be plans,” Jones says emphatically. “There has to be. There’s got to be an adult in the room. All of the adults have left the room in America, and maybe in most of the world now.

“And we have to make our leaders do it,” she reminds me, managing not to sound condescending or even pontificating. If anything, it feels like Jones is asking me nicely to do my part. “We have to be willing to sacrifice so that your daughter and other children will be able to breathe the air 50 years from now.”

Even as we ping-pong between supercharged topics, it would be difficult to overstate how very still Jones can sit. I suppose you could say she sits with an actor’s cultivated poise but, really, that doesn’t do it justice.

Over Zoom on a busy morning, both of us in busy New York City, Cherry Jones sits stiller than any human being has ever sat before. The comforting effect is similar to watching goldfish swim around a bowl. In a single conversation, she does more for my heart rate than a lifetime of deep breathing.

Significantly, too, Jones’s politics feel less a product of principle than conspicuous empathy. She is constantly imagining how people – healthcare workers, the coroner at Uvalde, the Transparent audience – might feel in a given situation and asking me what I think, too.

Imagining, of course, is a child’s gateway to acting, something Jones has wanted to do from the time she was four years old, performing the Three Wise Men at Christmas in her mum’s jewellery. Her mother, “daddy” and grandmother all supported the dream. “I just always wanted to put on someone else’s clothing, and try to become them,” she says.

Now, she might choose work that aligns with her values, but when she puts on the nursing scrubs – or the nun’s habit, or sits in the Oval Office – she’s also looking to learn from it. The relationship is reciprocal, and occasionally fraught.

Take The Handmaid’s Tale, about a dystopian society in which women are deprived of control over their bodies, particularly when it comes to pregnancy. Jones read Margaret Atwood’s book as soon as it hit stores in 1985. “Talk about prescient,” she says, name-checking the dual threats of Ronald Reagan and Jerry Falwell. “She just saw what was coming down the pike.”

I’ve always been a tomboy and gay, but when I started researching Eileen, I thought, ‘I’m really going to have to butch up here’

Getting asked to play “June’s mama” – as Jones affectionately calls her activist character and mother to series lead Elisabeth Moss – was a “thrill” given the source material. But the first season of the show was “so violent and dark” and the second season was even more so.

She found herself “pulling away from the series” on principle. “Atwood has always said that anything that was in that book, no matter how gruesome, is happening somewhere in the world right now to some woman. And I do believe that,” Jones says.

“But I also believe that if a woman is raped by 36 men, we do not need to see that woman being raped by 36 men, because who does that, at the end of the day, degrade and turn into…” She trails off. “I can’t even finish that sentence,” she says. And she doesn’t.

Her work on Succession has been more confusing to her than upsetting. “I was surprised that people loved Nan Pierce so much,” she says of the character offered up as a counterpoint to Logan Roy, the right-wing bully based on Rupert Murdoch.

Her personal prediction is that Nan will find her way back onto the series, though – at least in this case – she questions whether a matriarch is really any better than a patriarch under the shadow of unchecked capitalism.

“At the end of the day, even Nan is looking for a pay-out,” she says. “She appears on the surface noble, but I question her nobility.”

Her role on Transparent, Joey Soloway’s series about LA siblings who discover their father (Jeffrey Tambor) is a trans woman, is the one Jones wished for. Watching the first season with her wife – the Swiss filmmaker Sophie Huber – she even remembers asking aloud, “Why can’t I be on something like that?” Eventually, she’d be cast in a role based on the American poet Eileen Myles, who Soloway was dating at the time.

“I’ve always been a tomboy and gay, but when I started researching Eileen, I thought, ‘I’m really going to have to butch up here,’” says Jones, “which was a great deal of fun.”

She calls the show “Trans 101 for the country”, regardless of the fact that Tambor, the series star, was ultimately fired following claims of sexual harassment made by his assistant and a cast member. Tambor denies the accusations, and Jones is protective of the show’s reputation. “It was such a fun, positive show.”

And even if the allegations against Tambor didn’t compromise the legacy of Transparent, Jones can see the positive ramifications of Hollywood’s #MeToo movement.

The first table read for Five Days at Memorial featured a “stern” speech from Ridley: “Anything less than total respect for one another, and treating each other with kindness was not going to be tolerated.” At first, Jones felt “almost insulted” by the lecture: “I was like, ‘Who do you think we are?’”

It’s about everything that is smacking us in the face right now, from racial and economic injustice, to climate change, to the fact that our healthcare workers are now our frontline soldiers, and are going to continue to be our frontline soldiers.

But as she got to know Ridley, who co-directed the miniseries with Cuse, Jones understood the speech as a personal declaration: “It matters so much to him that people are honourable.”

In the end, Five Days, which was filmed in Canada during the pandemic, was one of the most special sets for Jones.

“I’ve never had that experience before with a community of actors who just couldn’t bear to be apart,” she tells me, recounting their weekly potlucks and the hours the cast spent discussing and debating the medical ethics of what was happening in the script – including the use of euthanasia when medical treatment and rescue have both been deemed impossible.

For Jones, the 15-year-old story is more relevant than ever. “It’s about everything that is smacking us in the face right now, from racial and economic injustice, to climate change, to the fact that our healthcare workers are now our frontline soldiers, and are going to continue to be our frontline soldiers.”

It’s about how understaffing issues in American hospitals are crashing into a Supreme Court that’s rolling back women’s right to healthcare. Mass shootings. Dangerous immigration.

To Jones’s mind, Five Days at Memorial is part of a larger conversation about the central role healthcare workers play in the US, a country that feels beset with new and more politically charged ways to die.

“How are we going to encourage people to get into the medical field at a time when what they’re having to deal with becomes more and more dire?” Jones asks me, a person who definitely doesn’t know.

“If a woman is having a miscarriage, what does a healthcare professional in Tennessee do now? Does the baby have to die in the womb, and infection set in before they will allow that dead child to be removed, without everyone in that operating room going to jail?”

A few days before our talk, a childhood friend texted her with the beginnings of an answer. The friend’s an oncology nurse now, and she saw the trailer for Five Days at Memorial in an airport and started crying.

She said that she had some “soul-searching” to do based on what she saw. “And she said, ‘I’m telling you that this series will be presented to nursing classes in ethics and death and dying.’”

Jones doesn’t know the path forward from here, but she believes with all her might that art’s the place to ask the question.

‘Five Days at Memorial’ can be streamed via Apple TV+ from 12 August

Yahoo News

Yahoo News