ChildLine at 30: are children happier than they used to be?

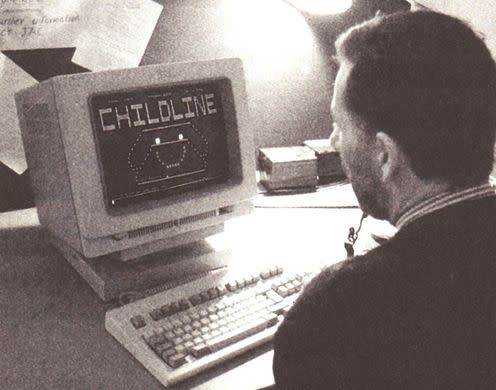

When ChildLine launched on October 30, 1986 as a phoneline for “children in trouble or danger”, it received 55,000 calls on its first night. The volume was unexpected and at first overwhelmed the social workers and volunteers manning the phones at the London switchboard.

The freephone number 0800 1111 was launched on the BBC programme Childwatch, produced and presented by Esther Rantzen, and followed revelations about adults’ experiences of sexual abuse as children. A survey for the BBC show That’s Life! had collected 3,000 responses, 90% from women, detailing abuse within the family home and by strangers, and the lack of public or institutional support available for children.

Yet 30 years on, and despite ChildLine’s ongoing work, recent reports suggest British children are among the unhappiest in the world. A survey published in February 2016, co-ordinated by the Social Policy Research Unit at the University of York, ranked the UK 13th out of 16 countries in terms of children’s “life satisfaction”, above South Korea, Nepal, and Ethiopia. So what is child happiness, and what role do children’s charities have in improving the well-being of young people?

Since its launch, ChildLine, now owned by the NSPCC, has helped over 4m children and young people, and in 2015-16 alone its website received 3.5m visits. But its success was by no means guaranteed at launch. Most newspapers ignored it, despite ChildLine’s receipt of a government start-up grant.

Professional concerns that the organisation might hinder children’s services and distress children rather than help them were much more common. Articles in The Guardian at the time, that we have looked at as part of research on the charity’s history, quoted social service staff arguing that ChildLine would not find a “hidden well” of child abuse and would increase the burden placed on social workers. Social workers suggested that counsellors should be trained professionals, rather than volunteers.

Responsibilities shift

ChildLine’s interventions reveal social anxieties about who is responsible for children’s well-being: the family, state, voluntary sector or simply everybody. The issue is a historical one: between the 15th and 17th centuries, the protection of children was often seen as the collective responsibility of a community.

The Victorians began to discuss “cruelty to children”, which was seen mainly as the responsibility of the voluntary sector – including the NSPCC which was founded in 1884. During World War II the emergent professions of psychiatry and psychoanalysis went on to sound warnings about the impact of children’s separation from their parents by bereavement and evacuation.

In the post-war period, there has been increasing focus from social scientists, governments, and charities on trying to measure children’s happiness, in order to improve it. This trend has not been without its critics. The sociologist Frank Furedi argues that childhood is over-surveyed, leading parents and the state to restrict children’s freedoms and autonomy, with little benefit.

How to define “childhood happiness” has also been contested. In the 1980s, ChildLine’s expansive definition of child abuse – taken to encompass anything troubling or concerning to a child – was criticised by some broadsheet journalists. The evidence from children’s contact with ChildLine, however, shows just how wide young people’s own interpretation was of the issues that were affecting them. These include bullying, and more recently sexuality and gender identity.

New triggers for contact

Data collected and published by ChildLine reveals how some of children’s main concerns have remained constant since 1986 – familial abuse and neglect, bullying, friendships – while others have evolved. In 2000, ChildLine observed an increase in children calling to speak about HIV/Aids. In 2005, it reported an annual rise of up to 30% in calls about self-harming. Last year, ChildLine was contacted every 30 minutes by a young person having suicidal thoughts.

ChildLine demonstrates how the measurement of children’s happiness is inseparable from the medium through which they disclose it. In the 1980s and 90s, the landline telephone provided an opportunity for some children and young people, but not others. Age, gender, socio-economic status and the ability to talk – in a private space or because of emotional stress or cultural reasons – were all discriminating factors.

From the beginning, many children wrote in to ChildLine. Now the rise of digital technologies has created new ways of listening to children. ChildLine’s internet chat service began in October 2009 and in 2015, 71% of counselling was done online. This may be allowing ChildLine to better reach out to new audiences, notably over the initial disclosure of mental health issues.

There remains disagreement among policymakers, academics and children’s charities about how to measure children’s happiness, and how to use data from ChildLine to do so. Still, the organisation’s analysis of counselling testimonies has been used to call for social and political change. Arguing that calls from children with suicidal feelings had risen by 14% in the previous year, in 2006 ChildLine lobbied through The Independent newspaper for a Department of Health investigation, and for peer support groups to become a statutory requirement in schools.

Assessing children’s happiness is incredibly complex. It depends on the measures used, the children contacted, and the prevailing issues of the day. While data from ChildLine is not perfect, it is a powerful tool for charting changing patterns in child well-being over the last 30 years.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Jennifer Crane receives funding from the Wellcome Trust. The research conducted for this article was part of a Wellcome Trust Small Grant, to hold a witness seminar about the history of ChildLine (Grant number: 200420/Z/15/Z)

Eve Colpus receives funding from the Wellcome Trust. The research conducted for this article was part of a Wellcome Trust Small Grant, to hold a witness seminar about the history of ChildLine (Grant number: 200420/Z/15/Z).

Yahoo News

Yahoo News