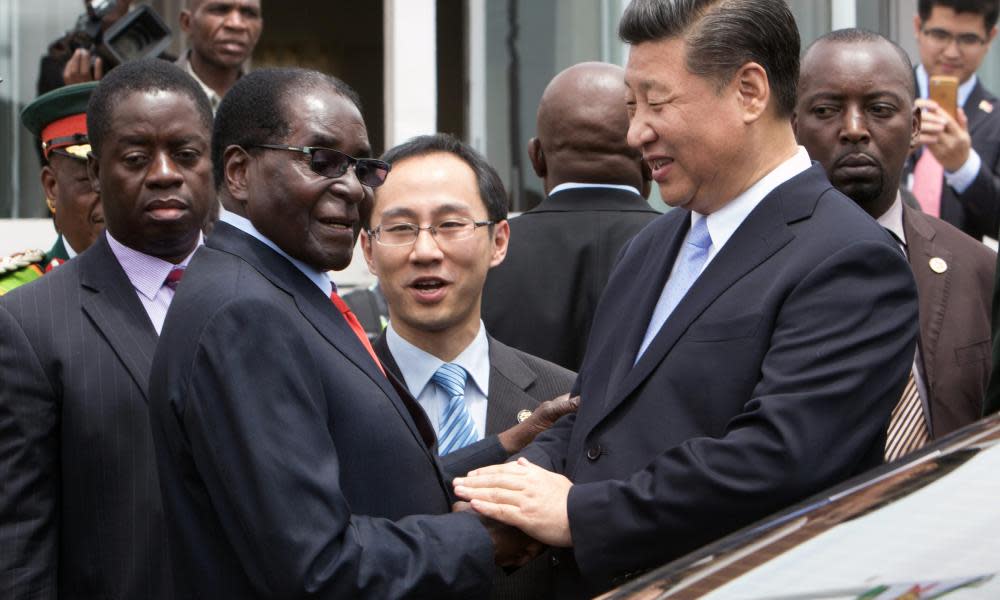

China turns its back on Comrade Bob to embrace change in Zimbabwe

Confirmation of Robert Mugabe’s ouster prompted revelry on the streets of Harare. “The Goblin has gone!” raved one.

Thousands of miles away in Beijing – for years Mugabe’s most powerful backer – there were no obvious signs of jubilation.

Robert Mugabe planned for everything, except his own retirement. He outsmarted his rivals and blindsided his allies for decades, and so most of the country had come to accept that he would stay in office until the day he died.

Emmerson Mnangagwa, now expected to take over from him, had boasted in May that Mugabe would die in the job. As such, there was no planning for the future.

One of the biggest questions now will be whether Mugabe can stay in Zimbabwe. Few ousted autocrats are allowed to stay on in the countries they once ruled, due to fears they may resuscitate their careers or become figureheads for opposition.

Mugabe may be an exception, because of his age and his role at the heart of Zimbabwe’s long liberation struggle. Throughout the most unusual of coups, Mugabe appears to have been treated with extreme deference by the generals holding him prisoner. Party members who ended his career have paid tribute to his historical achievements.

His much-hated wife, dubbed Gucci Grace for her spendthrift habits, may be targeted. But Mugabe is unlikely to want to face retirement alone, and any deal is expected to include protections for Grace and their children.

Wherever they end up, the Mugabes will certainly not lack for pension funds. By some estimates he holds about £1bn of assets, including vast property holdings and businesses around the country. Much of his wealth has also been invested outside Zimbabwe.

“China respects Mr Mugabe’s decision to resign,” foreign ministry spokesman Lu Kang told reporters, praising his “historic contribution” to Zimbabwe’s liberation. “He remains a good friend of the Chinese people.”

But experts believe China’s leaders will be both relieved and contented to see the back of “Comrade Bob” – a suspicion reinforced by the approving tone coverage of his demise has taken in the Communist party-controlled press.

“We need change in our country,” China’s official news agency Xinhua – whose correspondents’ dispatches are expected, above all else, to reflect the party line – quoted one Zimbabwean teacher as saying of Mugabe’s resignation.

“We’re very happy,” another Zimbabwean told party mouthpiece the People’s Daily. “Finally things will change.”

Ross Anthony, an expert in China-Africa relations from South Africa’s Stellenbosch University, said that while Beijing had backed Mugabe since his days as a Marxist revolutionary in the 1970s, it had increasingly seen him as erratic, an embarrassment and a threat to Chinese investments.

A case in point was Mugabe’s controversial indigenisation law, which required all foreign companies to be controlled by Zimbabweans and was a particular blow to Chinese interests in its diamond industry.

(November 14, 2017) Tanks on street

Zimbabweans post video footage of tanks moving on the outskirts of the capital, Harare. Read more

(November 15, 2017) Mugabe detained

The army declares that Robert Mugabe has been detained at his residence as it takes control of the streets of Harare. It denies that a coup has taken place. Read more

(November 16, 2017) Digging in

Mugabe refuses to step down during talks with generals. Envoys from the Southern African Development Community are dispatched to Harare to hold talks at the presidency. Read more

(November 17, 2017) A public appearance

The president shocks Zimbabweans – and the wider world – by appearing in public at a university graduation ceremony. Calls for Mugabe to go only increase, but he clings on. Read more

(November 18, 2017) Protests

Thousands of protesters flood Zimbabwe's streets demanding Mugabe's resignation. Read more

(November 19, 2017) The resignation speech that wasn't

The head of Zimbabwe's war veterans' association says Mugabe should give in "now", but in another twist, the 93-year-old gives a public address that makes no mention of resigning. Read more

(November 20, 2017) Impeachment plan

The once-loyal Zanu-PF, the ruling party, outlines a plan for launching the impeachment process in parliament the next day. Read more

(November 21, 2017) Mugabe goes

Parliament reconvenes for a session to impeach Mugabe, which is interrupted when the speaker announces that the president has resigned. Read more

“I imagine there are quite a lot of officials in Beijing who will be happy to see Mugabe go,” Anthony said.

Since the curtains began to fall on Mugabe’s 37-year reign last week, Beijing has done little to hide its view that its longtime ally was a difficult customer.

In an article for Xiakedao, a social media account run by the People’s Daily, Zhang Weiwei, a former interpreter for Deng Xiaoping, recalled a tetchy 1985 encounter between Mugabe and the Chinese leader.

As Deng, the architect of China’s economic opening, prepared to receive Mugabe in Beijing’s Great Hall of the People, he complained about their last meeting, four years earlier. According to Zhang, Mugabe had used that audience to criticise Deng for supposedly rejecting Mao Zedong and his tumultuous Cultural Revolution. “He grumbled a bit,” Deng told his then foreign minister, Wu Xueqian, according to the account.

After a second, similarly testy meeting with Mugabe, Deng urged his visitor not to repeat Mao’s mistakes by destroying Zimbabwe’s economy in the name of ideology: “Comrade Mugabe … please pay special attention to our leftist errors.”

Zhang concluded Mugabe had ignored Deng’s warning. Had he not done so, “Zimbabwe might not have gotten itself in into this difficult situation”, he reflected.

Opinion pieces in China’s state-run media this week have also highlighted the economic turmoil Mugabe inflicted on Zimbabwe. “The country has turned into a big slum plagued by hunger,” one scholar wrote in the Global Times.

Anthony said that, for Beijing, embracing life after Mugabe was in many ways “a no-brainer”.

“Chinese diplomacy is very practical and very adaptable. It’s still going to be Zanu-PF and they have a deep relationship with China, so it’s not even that much of a game-changer for them.”

Andrew Nathan, an expert in Chinese foreign policy from Columbia University, agreed Beijing would have no bones in switching allegiance to whoever replaced Mugabe. “I don’t think it cares much [what comes next]. It wants to be on the good side of the regime … They did cooperate with Mugabe; they will cooperate with his successor.”

Chinese profiles of Mugabe’s likely successor, Emmerson Mnangagwa, painted him as a reliable, China-friendly figure who had studied Marxism and military engineering in the Middle Kingdom.

“In past interviews Mnangagwa has repeatedly emphasised that Zimbabwe needs to ‘look east’,” a report in Shanghai’s The Paper said approvingly.

Additional reporting by Wang Zhen

Yahoo News

Yahoo News