Classic car cold cases: the search for a 1909 Rolls-Royce Silver Ghost used by Lawrence of Arabia

The RMS Titanic sank in the North Atlantic on 15 April 1912, taking the lives of 1,500 passengers – including the owner of one of the most famous cars ever to go missing. He was Fletcher F. Lambert-Williams, a director of the Mono Service Company, who three years previously had purchased a new dark blue Rolls-Royce Silver Ghost with the chassis number 60985 and fitted with Maythorn coachwork.

It received a London registration number LC1928 and was given the name of Blue Mist; a Rolls-Royce custom at that time was to name each Silver Ghost it made.

The Blue Mist was acquired by the Rt. Honourable Earl of Clonmell, an Irish horse breeder and Captain in the Royal Artillery, who used the car until 1914 when he went to Europe to fight in the First World War.

Mr Burge, Lord Clonmell’s chauffeur, placed it into storage and maintained it until July 1916 when he was instructed to look for a buyer for the car.

At that time Lord Clonmell met Aileen Bellew who was about to leave for Cairo to meet her new husband Hugh Lloyd-Thomas, who worked at the British Embassy there. She wanted to purchase the car for her husband as a wedding present.

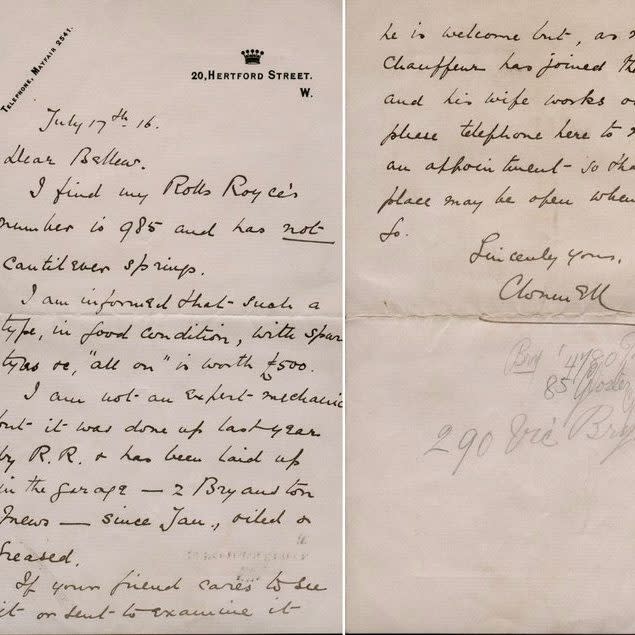

In negotiating the sale a letter from Lord Clonmell, dated 17 July 1916, explained that the car had been overhauled by Rolls-Royce the previous year but was in good condition and worth, he thought, £500.

In a letter of 15 September 1916 from a Mr A.J. Bray, of Gloucester Mews in London, who claimed to be a Rolls-Royce expert, stated “the car appeared to be in good order, its tyres were in good condition with just some paintwork and woodwork needing to be touched up”.

On to Cairo – and a meeting with Lawrence

At the end of 1916 the car was shipped to Cairo and in July 1917 after a few months of ownership Mrs Lloyd-Thomas found herself in the British Officers’ club when a gentleman wearing full Arab dress was introduced to her; this was Colonel T.E. Lawrence – more commonly known as Lawrence of Arabia.

History records that Lawrence, who had come to Cairo to see General Allenby after the capture of Aqaba, had seen the Blue Mist parked outside the club and informed Mrs Lloyd-Thomas that he was going to “commandeer” her car “in the name of His Majesty’s Government”. Having no option, she agreed.

Mrs Lloyd-Thomas never saw her car again – other than the Spirit of Ecstasy mascot from atop the radiator plus the enamelled Blue Mist badge, which she subsequently received in a parcel from Lawrence.

What she did not know was that the original Maythorn coachwork had been removed and replaced by a crude wooden box, which was found to be better equipped to carry a heavy cargo of arms, ammunition and supplies when it joined several other cars as a tender to Lawrence’s Hedjaz Armoured Car Battery in the Arab conflict.

Evidence shows that Lawrence entered Damascus on 1 October 1918 in the Blue Mist as the Great Arab Revolt campaign was ending. Four days later he was chauffeured out of Damascus by his driver, coincidentally named Rolls, on the start of his long journey back to England.

Then the car disappeared.

Sifting through the evidence

One story suggests the Blue Mist was discovered, abandoned, in a sand dune beside the road outside Cairo, and when fitted with a new battery it started first time.

However, I am fortunate to have communicated with Richard Weston-Smith, who lives in Santa Barbara, California, the grandson of Aileen and Hugh Lloyd-Thomas, who retains many family records of the Rolls-Royce chassis number 60985.

Weston-Smith holds a letter dated 3 September 1919 from the Cairo Motor Company at 24 Rue Saleh El Dis in Cairo, which indicates that his grandparents’ car was repaired and restored and they were ready to sell it.

He felt sure that the Maythorn coachwork removed by Lawrence would have been returned to the Embassy as it was “half the worth of the car” and that the Cairo Motor Company would have sympathetically restored it in the 12 months that they had it. There is, however, no evidence of this.

The anomalies in the letter from the Cairo Motor Company to Mrs Lloyd-Thomas about the age of her car require explanation.

The letter states that the garage dated the car as a 1910 model, not a 1909 car. Weston-Smith told me that the garage probably “during the execution of repairs, determined the age of the car, which implies to me that they did not have the documents at that time and estimated its age”.

Also, Mrs Lloyd-Thomas’ mistake in the letter suggesting it was a 1913 car was due to the fact that she probably “would not necessarily have known, or cared, what year the car was. From the time she bought it and it was shipped to Cairo and then commandeered by Lawrence, it was probably actually in her possession for no more than three or four months”, suggested Weston-Smith.

A deal had been orchestrated by the Cairo Motor Company on behalf of Mr and Mrs Lloyd-Thomas who at this time, after the Arab conflict, had been sent to the British Embassy in Rome.

The last recorded owner

In 1919 the car was sold to a Mohamed H Elshafe of Sharia Abou Yeleb, Boulac, Cairo, Egypt, details of which are noted on the Rolls-Royce build sheet for 60985. It has not been seen or heard of since.

Weston-Smith said that his research into the name Elshafe showed it to be the Egyptian equivalent of Smith in commonality, and that neither of the two families in the area wealthy enough to afford such a car had that name.

I asked retired Egyptian police officer Francois Shakhir, who lives in Zamalek near Cairo, to carry out some enquiries and his report suggested that the house in Sharia Abou Yeleb, Boulac, no longer existed but could have been a business connected to religion or the law.

The Cairo Motor Company still exists but has nothing to do with its 100-year-old namesake.

The area around Boulac was industrial back in 1919 but is now the home to embassies and government buildings, upscale hotels overlooking the River Nile and museums, including the Museum of Antiquities which had been operating from a warehouse in the area since 1858.

While Shakhir discovered that “many years ago” it had several vehicles in its collection, the museum directed him to the new Royal Vehicle Museum on July 26 Street, also in Zamalek.

He found very little was officially known about the Lawrence car but he did discover from both a staff member and a visitor that a vintage Rolls-Royce was believed to be one of a group of 22 “gifted” cars being restored on commission to the museum.

A royal reprieve for Blue Mist?

It was also believed that Prince (later King) Faisal, who was a friend of Lawrence, had expressed an interest in owning the car, although if it was in the Royal collection Rolls-Royce surely would have known about it.

Other information suggested that several of Lawrence’s Hedjaz Battery group of cars, many of which were in poor condition, had also been seen in the same area and at the same time as 60985, when it was delivered to the garage.

In 1919, as the Blue Mist was being repaired, Egypt was seeking independence from Britain, riots broke out, public and private vehicles were being burned and the British were forced to flee for their own safety.

An insight into the riots are explained on page 225 of The British Community in Occupied Cairo, 1882-1922 by Lanver Mak, which provides a vivid insight into how much hatred the Egyptians had for the British at that time.

The description of riots and chaos suggest the worst for 60985. The car, clearly a symbol of British rule, would have been extremely vulnerable, even in the hands of its new Egyptian owner, who would clearly have had to hide it or remove it from the area.

I am grateful to the huge amount of people who have researched both Lawrence and the Silver Ghost chassis number 60985 and have, in respect to them, simply provided a precis of their findings to the point where the car went missing.

Outstanding questions

Several questions, however, require further investigation.

Was the Cairo Motor Company attempting to undermine the value of the car in their letter to its owners, who were negotiating from another country and unable to see the completed car? Indeed, had the car actually been repaired at all and/or were parts of other cars used to repair 60985? Was payment from the sale ever sent to Mr and Mrs Lloyd-Thomas?

The Historical Society in Biggleswade, the home of Maythorn coachworks, could find no record of the bodywork from 60985 ever being returned to the company. Did it survive and, if so, where is it now?

As the skirmishes continued long after Lawrence’s departure, is there evidence that some of his Hedjaz Battery cars, perhaps including 60985, continued to be used as fighting machines in and around Cairo at that time?

The identification of the Blue Mist, if it still exists, relies on a chassis plate secured with four screws which should display 985, with a corresponding engine number of 985. Could it have been removed or simply fallen off?

These queries may never be answered but it was clear that our enquiries about Blue Mist stirred up interest in Cairo, which may or may not prove productive; only time will tell.

For new and used buying guides, tips and expert advice, visit our Advice section, or sign up to our newsletter here

To talk all things motoring with the Telegraph Cars team join the Telegraph Motoring Club Facebook group here

Yahoo News

Yahoo News