A climate-themed debate? The Democrats owe it to voters

Twenty candidates – ten candidates per night – will take the stage during this week’s two-part Democratic primary debates. Each debate will last two hours, and, excluding introductions and interruptions, each candidate will have roughly 12 minutes of total speaking time. How much of that can we reasonably expect to be devoted to the climate crisis?

If past debates are any indication, not much. There were no direct questions about climate change posed in either the 2012 or 2016 debates. In refusing grassroots calls for a debate focused on climate change, Democratic National Committee chairman Tom Perez has promised this time would be different. In a Medium post composed after backlash to his decision, Perez wrote that he considers climate a top issue, and “made clear to our media partners that the issue of climate change must be featured prominently in our debates”. Given that network news spent more time covering the Royal Baby in one week than they’d spent in a year on climate change, that’s not exactly a convincing sell. If the DNC really did care about climate as much as Perez claims, it’d see the debate stage as a chance to offer a valuable counter-weight to the relative silence across television news about the climate crisis.

Why, moreover, would the DNC let such an opportunity go to waste? As the Trump administration continues to deny the basic reality of climate change – with some even cheering it on – fully owning the climate challenge as their own could be a boon for Democrats. Recent European parliament elections saw a flood of voters to the European Greens, as the climate crisis emerged as a top concern for many on the heels of massive Fridays for Future demonstrations and Extinction Rebellion in the UK. Climate fears are beginning to take hold of voters in the United States as well, and the DNC would be stupid to not capitalize on the fact that their party is the only one with any nominal claim to be taking the potential end of the world seriously.

The climate crisis isn’t an “issue” so much as the foundations on which all politics is going to play out

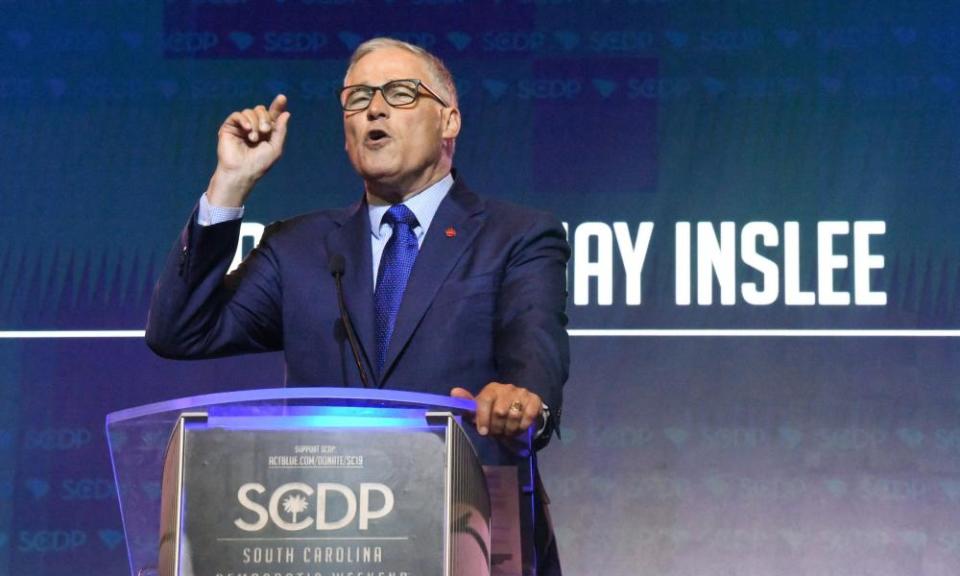

If the DNC isn’t going to take advantage of that fact, then Democratic presidential hopefuls should. When candidate Jay Inslee inquired about doing a special climate-themed debate, the DNC threatened to bar him and any other candidate who participated from the official primary debates. Why not dare them to try?

Given the anti-establishment mood of many voters, it could play well for independents to stick it to the stingy party apparatus. Virtually every front-runner except for Joe Biden has backed the idea of a Green New Deal, and even he has called it a “crucial framework”. Fifteen have also supported the idea of a climate debate. If climate change really does matter to them, then the coherent move would be to rebel against the DNC and give voters a chance to hear their thoughts on the greatest existential threat facing humanity. With Republican leaders like Mitch McConnell and Matt Gaetz already starting to come around on climate, Democrats’ homefield advantage on the issue may not last long.

A climate debate shouldn’t be about haggling over targets and degrees and parts per million, but about the full scope of what the challenge actually entails. From housing to immigration to healthcare, there’s no policy field which won’t be touched by rising temperatures in the coming decades. Contra Perez, the climate crisis isn’t an “issue” so much as the foundations on which all politics is going to play out.

Making that a core concern for the party is an opportunity for Democrats to do something they haven’t in a very long time: present a plan for how to make people’s lives better. What candidates can bring forward – or fail to – is a vision for what a fairer and more democratic low-carbon world could look like, most thoroughly articulated so far by advocates for a Green New Deal. Promising to be better than Trump on climate is no recipe for the kind of rapid decarbonization required to save our collective skins.

A climate debate, as such, should try to accomplish a relatively simple goal: to make candidates explain as succinctly as possible their plans to keep warming below 2C or less, and deal with the effects of whatever level of warming we do get. Leading climate scientists and energy experts can pore over the candidates’ answers in the days and weeks afterward, and evaluate how far each candidate’s plan will actually get us toward that goal.

Then voters can decide whether those plans sound like they would build a world worth living in – DNC be damned.

Kate Aronoff is a writing fellow at In These Times. She covers elections and the politics of climate change

Yahoo News

Yahoo News